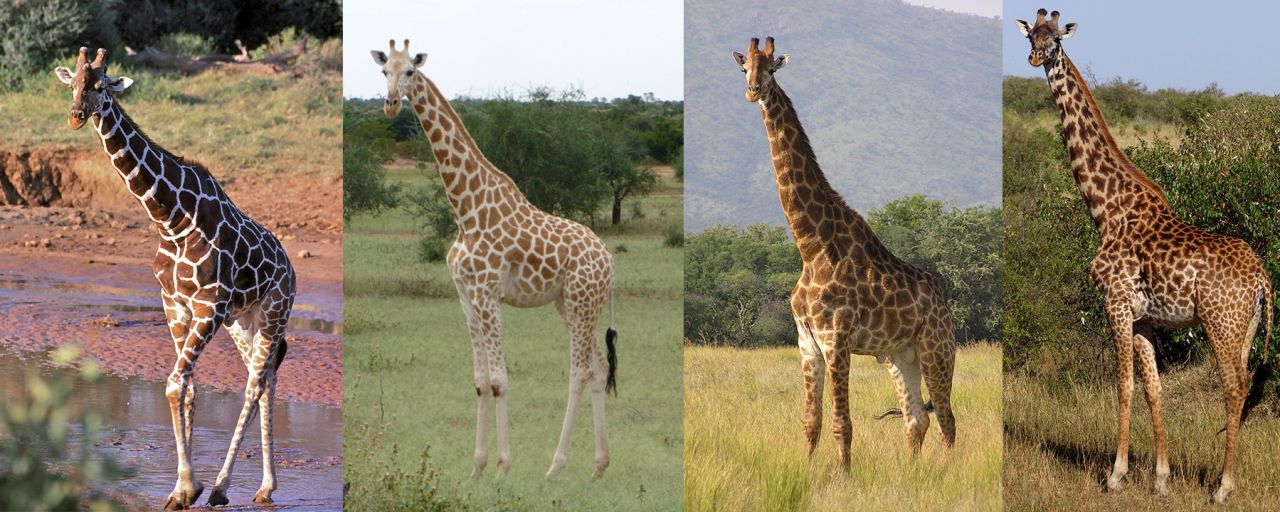

A recent study proposed that giraffes are actually comprised of four main species (from left to right): reticulated, northern, southern and Masaai.

This September, Earth’s single giraffe species suddenly became four. “A Quadruple Take on the Giraffe: There are Four Species, Not One,” wrote The New York Times. “Giraffes aren’t just giraffes,” reported The Washington Post. A study published in Current Biology, a prominent science journal, had reshuffled Africa’s nine recognized giraffe subspecies into separate species:the southern, the Masai, the reticulated, and the northern.

While this redrawing of species boundaries could be key for conservation, not everyoneis convinced it was right. After all, the study is part of a centuries-old scientific squabble over how to define a species.“The fact is, these ‘four species’ are no more real than they were before in any biological sense,” says Jerry Coyne, a professor of ecology and evolution at the University of Chicago and author of the 2004 book “Speciation”.

Coyne sticks to what’s known as the traditional “Biological Species Concept,” which says that even if two wild creatures look somewhat different and don’t always cross paths, but they can create fertile offspring—they’re both members of the same species. “But with giraffes,” he says, “we just don’t know.”

Giraffes live throughout different regions of sub-Saharan African and scientists have long known that these groups are genetically different. In fact, two of the study’s newly-minted species were recognized as genetically distinct centuries ago, but were lumped back together more recently. A decade ago, evolutionary biologist Robert Wayne co-published results suggesting that not four, but six giraffe populations have long been genetically cut off from each other.

Unlike Coyne’s approach, the study used genetic differences to separate the giraffes. This is a method of defining species by their “phylogenetics,”or by their shared traits. In this case, Goethe University researcher Axel Janke found genetic markers, such as mutations, that were common among certain giraffes and not shared by the others. This suggested to him that there has been very little gene sharing between the groups.

But by Coyne’s definition, this doesn’t prove that giraffes are reproductively isolated. “The only way to show whether or not they are separate would be to move the wild giraffes into the same area and see if they produce a fertile offspring,” he says. While the different subspecies are known tohybridize in captivity, there is very little evidence of this in the wild.

“The Biological Species Concept is more meaningful because it helps to explain one of evolutionary biology’s most profound questions”: Why is nature discontinuous? he says—why is it not all “one big smear” that can exchange genes?

Grouping species by what they have in common, Coyne says, can’t answer this. “You start getting into these questions of, ‘How much difference does it take to make two populations, which can end up being quite arbitrary,” he says. After all, the difference between some bird species or closely-related flower species ends up being just a few genes. Genetics-wise, chimps and humans are almost 99 percent the same. The Biological Species Concept is more clean cut.

Still, with what we know about hybrids between species in the wild, Janke calls Coyne’s approach too “pure” and says that it’s going out-of-date.

Others in the field call the species confusion more philosophical than anything. This becomes a problem when we try to apply it to something very real, such as protecting Africa’s giraffes. Whether one, four, or six species, giraffes have experienced a 40 percent plummet in population over the past 15 years. They’recurrently listed as a species of “least concern” by the IUCN and unlike alarm bells ringing for Africa’s elephants, gorillas, and rhinos amid the poaching crisis, they receive relatively little attention.

“With now four distinct species, the conservation status of each of these can be better defined and in turn added to the IUCN Red List,” said study co-author Julian Fennessy of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation in a release.For example, said Fennessy, there are now less than 4,750 Northern giraffes and fewer than 8,700 reticulated giraffes in the wild. “As distinct species, [this] makes them some of the most endangered large mammals in the world.”

Whether the new study will influence IUCN’s listing is still an open question.