Rhiannon Kirton is a wildlife specialist and one of the organizers behind the viral online movement, Black Birders Week. Although the week has ended, the work has just begun for this grassroots group. Black AF in STEM is now challenging outdoor brands to show the Black community that they truly value them by taking action. As an avid mountain biker, Kirton took the opportunity to pen a call to action directed towards the larger outdoor industry.

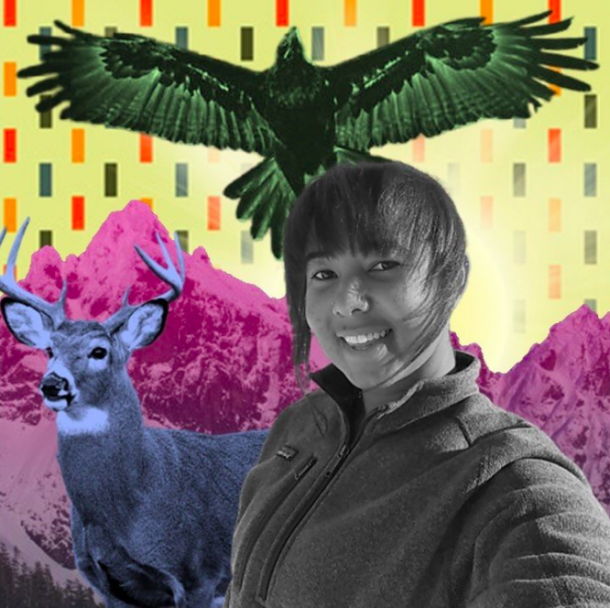

This artistic portrait of Rhiannon Kirton was created by artist Jose Gonzalez after Black Birders Week.

“We have had an amazing response to Black Birders Week but we need to carry on this momentum when the week is over,” Kirton said. “As Black scientists, birders, bikers, hikers, hunters and anglers we have supported your companies by buying your products and relying on their functionality when outdoors. Now we need you to support us! Black people need to see others like them in these spaces. Leaders in the (outdoor) industry need to stand behind us and show that representation matters.”

Kirton is a global citizen, having lived in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Her field experiences have taken her across the globe to Tasmania, Australia, British Columbia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Kirton is currently completing an interdisciplinary Master of Science degree in Geography at The University of Western Ontario, with a special focus on spatial ecology and movement of white-tailed deer, the most widespread game species in North America. During our interview, which has been edited and condensed, Kirton touched on her passion for wildlife and the great outdoors, the global impact Black Birders Week has had, and the increased representation she would like to see within the larger outdoor industry.

Q: What experiences sparked your passion for the natural world?

Rhiannon Kirton (RK): So I actually did not grow up in North America. I grew up in the UK and in Australia. I was born in Warwick England, and grew up in a place called Ocean Shores, just north of Byron Bay, as a young child. So when we lived in Australia, it was a very rural area right by the beach. I think that’s where a lot of my passion came from, living in the outdoors and spending time outside every day. I saw snakes regularly and the wildlife in the area was fairly biodiverse, which as a child, I didn’t realize, but it did have a lot of influence. When we lived in the UK, in Somerset, I would ride horses and spend all my time outdoors and in the woods. So I think that’s really where my passion comes from having grown up in those spaces and exploring the natural world. I’ve just continued on with that into my career. Obviously in Australia, when I was growing up Steve Irwin was such a driving force behind Australians connecting with snakes and reptiles and other animals that you might not necessarily have an affinity with. I’m still terrified of snakes, but I definitely think seeing him on TV, and growing up with those nature programs really fueled my passion.

Q: Was sharing and appreciating the natural world part of your childhood?

RK: I started off wanting to be a vet, and I had all these grand plans of being a wildlife vet. In Australia, most vets do actually handle wildlife fairly frequently, like koalas. In England it was not really the same. They don’t spend as much time working with wildlife. So it’s kind of a bit of a different ball game, but my mom definitely encouraged me to do whatever I was passionate about. I always tell this story about my mom. When I was doing my A levels, I did this optional course where you write a paper and you could pick any topic that you wanted to write about. I decided that I wanted to write about wolves and wolf behavior. I wanted to show that wolves are not as terrifying as people think they are, there is a long history of wolves being associated with malevolent spirits in European folklore. So I contacted our local safari park, which was Longleat. Longleat is an institution in the UK, and I decided to shoot my shot and email them and ask them if I could visit, and speak with some of their animal keepers. They agreed to let me visit, but because I didn’t have a driver’s license yet, my mom had to come with me. I went for three days to observe the wolves and their behavior and she spent three days sitting in a wolf enclosure in a safari park just so that I could write my school paper. It was completely optional. So I guess that’s a good example of how supportive she has been. Some of my friends could not believe that my mom actually sat in an enclosure with me for three days just to watch some wolves. The animal keepers actually let us help them feed the wolves, and my mom was right there by my side throwing the meat to them.

Wolves used to roam the English countryside, but died out in the Middle Ages due to hunting campaigns and deforestation. Now they are back at Longleat Safari Park. Credit: Jeff Welch/Flickr

Q: What impact has Black Birders Week had on you?

RK: I’m a wildlife scientist and I currently use geography-based tools. Since Black Birders Week, I have a newfound appreciation for those sorts of disciplines that are more human-focused because they do deal with questions like, how and why do we have less Black people in the outdoors? Those sorts of questions are often looked at through geography. Something else that was brought to my attention during Black Birders Week was the way that maps have been used to colonize the world and how people have used maps to disenfranchise minority groups. For me, I have this whole new perspective on my discipline that I’m in, and how we can change it and decolonize it. That has been profound. Also the sense of how many other people are out there has been huge. The truth is there are so many people who felt like they were the only ones, but they’re not. Black people just don’t get advertised as much enjoying the outdoors or working as scientists. To have this greater sense of community has been really great. At first we did not think it was going to be that big of a thing, and to see that this little idea go viral, and reach so many people around the world has been so impactful.

Rhiannon helping release a Tasmanian devil alongside Dr. David Hamilton of the University of Tasmania. Credit: Dr. David Hamilton

Q: During Black Birders Week there were a lot of discussions about racism and microaggressions that participants experienced while enjoying nature or simply going about their daily life. Could you tell me more about your experiences in the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada?

RK: What I realized was that a lot of microaggressions become normalized that shouldn’t be normal. My sister actually shared this video that appeared on BBC Spotlight last week. This mixed-race girl grew up in Cornwall and went to school in Plymouth, which is close to where I grew up in the UK. She read a spoken word poem called “Where do I draw the line?” She was talking about how kids would want to touch her hair when she was in school. She thought nothing of it, but people would say the N-word in songs. She thought, well, that’s fine, she didn’t challenge it. She was talking about how when she spilled chocolate milk on herself some kids said, “that’s okay, it’ll just blend in.” This spoken word poet asked, where do you draw the line? What is racist? How many of these microaggressions did we grow up listening to? Until they just became part of our everyday life. It was really interesting to listen to. I said to my sister, this was exactly the way that we grew up. It felt like every single thing she talked about was something that I could resonate with. There are some things that I just heard so much growing up that I don’t think of them as being a problem. That’s another thing that was mentioned throughout Black Birders Week.

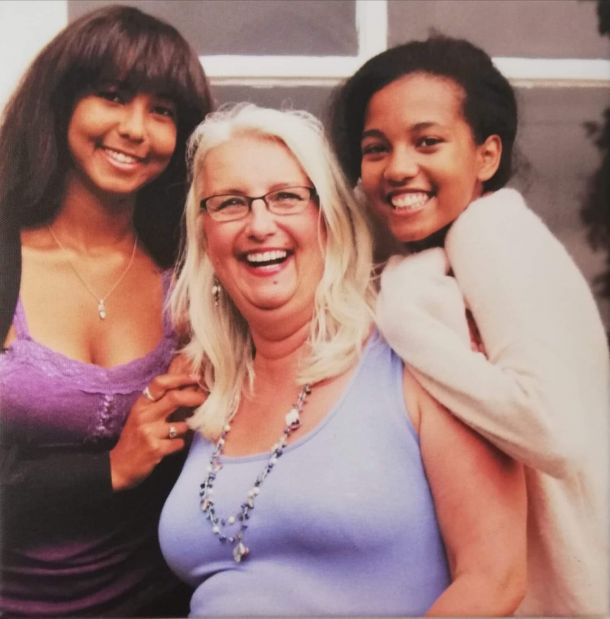

Rhiannon Kirton (left) pictured with her mother Fiona (middle) and sister Ayesha (right).

For Black women, your hair is a big thing. People always ask, can I touch your hair? Or they ask, what is your hair like? When my sister and I were in school, people would always want to touch our hair all the time. My classmates used to put pencils in my hair and hide them there to see if I would notice, which in hindsight is quite problematic. I remember when we were really little kids, probably five years old, this one kid on the school bus tried to touch my sister’s hair. My sister said ‘don’t touch me.’ Her hair is much more textured than mine is. He kept trying to touch it, every day, and she kept saying she did not want him to touch her hair. He touched her hair anyways, after multiple days of her telling him not to. She was so frustrated she hit him over the head with her umbrella. Even at the age of five, you get the sense that your hair is a spectacle, or that you’re different. Your hair becomes a way to point out how different you are from everyone else. There have been so many conversations around policing of Black women’s hair. I remember a few years ago, the U.S. military said, Black women can braid their hair now. I think this is a big thing for people. Especially being Black and mixed race, something that we’ve spoken about a lot is we get a lot of push back from both sides because you’re dark enough that you don’t fit in as white, but then sometimes in the Black community, people will say you’re not really Black. These were conversations that we discussed a lot during Black Birders Week.

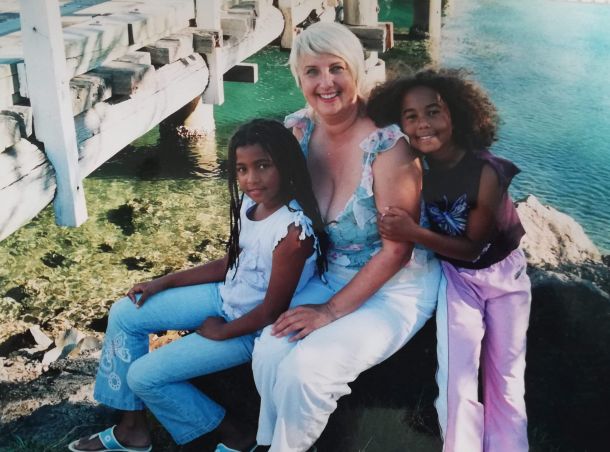

A Kirton family portrait taken in Brunswick Heads, Australia.

We lived this strange existence in Australia. Australia’s national identity is very white. On the whole, outside cities like Melbourne and Sydney and Brisbane, there aren’t a lot of non-Aboriginal people of color, generally speaking. Even though there’s a huge Aboriginal population, most Australians don’t have enough understanding of Aboriginal Australians. They were the original inhabitants of Australia, and this kind of white identity that Australians have taken on is so exclusive of that. In the UK, we would get picked on for being brown, but in Australia it was only the Aboriginal kids who got picked on and we were largely left alone. It was a very strange way to grow up. We weren’t white, but then we weren’t picked on like the Aboriginal kids were. It was so sad to see that. Even to this day, Australia has a lot of work to do in regard to Aboriginal people, making up for what was taken from them, which is not really even possible because of the whole stolen generation of children. You can’t just magically give them back. I think it was definitely interesting to grow up in those two different spaces and it’s been really eye opening to me to learn so much more about the Black communities in Canada. There are historical perspectives that no one talks about, I learned the other week that historically the town I live in had a KKK chapter. Why would the KKK be in Canada? I thought the KKK was an American thing. Then I kept reading and I found out that where I live was actually one of the last stops on the underground railroad when they were freeing slaves. There is a whole history of Black community in the city that I live in, it’s just not very visible. So I’m definitely going to be doing more work, to find out about that. The other crazy thing I learned, which is the most mind blowing, is that the cowboy responsible for bringing cattle to Alberta was actually a Black cowboy named John Ware. It was just the craziest thing to me to find out this huge industry that’s part of the identity of Alberta was actually started by a Black man.

Q: Have you ever experienced any challenges or dangers when you’ve been conducting fieldwork or enjoying the outdoors?

RK: If someone says something racist to me in Canada, I’m not worried that they’re going to shoot me. Whereas in the States, the gun culture is such a huge part of this whole thing. When I was mountain biking in Oregon, I got lost. I was around Bend, Oregon which is in the high desert. It was the middle of summer and when I realized I was lost, I considered going back, but that would have added hours onto my journey. As I was finding my way, I came upon this development of houses. I thought I could probably just walk across this building site because it probably leads to a main road. There was a sign that said ‘No Trespassing.’ People think of Oregon as this blue state, but in the eastern part of the state it’s definitely not as blue or progressive as people think. So I’m standing there and I’m thinking, do I cross this building site? There is no one there, it’s just a building site. I saw that there was a man in his truck. I literally stood there for about 10 minutes walking back and forth. Thinking if I trespass, will I get shot? Will someone think that I’m suspicious because I’m Black in America and I’m in the outdoors, you know?

Rhiannon mountain biking at Farmer John’s bike park in the northwest of England. Credit: Sam Hewitt

After pacing back and forth, I decided to take my chances and hope I don’t get shot because I have a mountain bike with me. Obviously I’m not trying to trespass. I’m not doing anything that I would think of as suspicious. Sometimes just being Black and in the outdoors is enough. When I crossed the building site only the foundation was laid at the time. Ahmaud Arbery was killed for doing exactly what I did, but he was looking inside a building site, and I was crossing a building site with my mountain bike. I was lucky cause you hear all these other stories of people who weren’t lucky. You shouldn’t have to be lucky just to simply survive. When I was younger, I didn’t really think about these things. I was very gung-ho about going wherever I wanted to go. Having spent more time in the States, I now know, obviously that is not always advisable.

Q: What changes would you like to see within the outdoor industry?

RK: This is a similar conversation that I had with the brand Yakima. I realized that Yakima is a really niche brand. I never thought it was, but I guess that’s just my experience. I guess that is part of it, making those sports and industries more accessible to begin with. That really starts with representation. My boyfriend is a road biker, and I mentioned I was speaking to Yakima. He was like, who’s Yakima? Even within the outdoor industry, every discipline is so different and it can be quite insular. In the outdoor industry, lots of people use their own staff for their marketing, especially if they’re small companies. If you don’t have any Black staff members, you’re not going to have any Black people in your pictures. So I think it is this multifaceted issue, but we need better representation in marketing. There needs to be better diversity in who you’re hiring, but to do that, those industries need to be more accessible along with a lot of outdoor sports. I learned to snowboard when I was at university. I had a part-time job and I saved up and paid for it as someone who grew up in a single parent family. We didn’t have the money to go skiing or to mountain biking or to do any of those things. I think part of it is outreach. What can brands do to engage communities that would not traditionally be part of their demographic? Could bike brands or hiking brands have youth programs where they have access to equipment, or learn how to do that sport? I live in Ontario, so we’re in the middle of all of the Great Lakes. Kayaking is a huge sport here, but I remember reading that there was a young Black boy, Jeremiah Perry, in Toronto who went on a school trip and they knew he didn’t pass the mandatory swim test, but didn’t plan adequately. He drowned on the trip. Would that have been acceptable from an affluent, white school? I doubt it.

In the Black community, or other minority communities that have been socioeconomically disenfranchised for the last 400 years since slavery, we don’t have that kind of extra capital for our kids to be able to learn to kayak or canoe or mountain bike or snowboard. Especially in countries like Canada, those sports are part of the national identity. Recognizing this inequality comes with a wider conversation about making the outdoors more welcoming. Patagonia can put all the Black people in advertising that it wants, but if you actually go outdoors and experience racism from people in the outdoors, you’re still not going to want to go there. I do think these brands have such a big part to play in showing that we are out there because I mean, we are. Black Birders Week showed the world that we actually are recreating outdoors. Marketing has a big part to play in displaying better representation. You are not going to want to go explore the outdoors or be inspired to do so if you can’t see yourself in those spaces. I was talking to someone who participated in Black Birders Week, and she said that she saw a Subaru commercial that actually had Black people in it and she was so excited she actually went out and bought a Subaru.

These brands need to help get rid of the idea that exploring the outdoors is a white thing. I’m doing a webinar tomorrow with a guy who is a Black war veteran, Chad Brown. He is also a fly-fishermen, he runs Soul River Inc. I have never been fly-fishing. I’ve been to places where there is fly-fishing, but fly-fishing is one of those things like hunting or angling, that appears to be very white. In an article that he wrote about fly-fishing he said that he has been told that he doesn’t belong, or that he’s trying to take the river from white people. Maybe those white people wouldn’t think that the river belongs to them if they saw more Black faces in the outdoors, whether that be through advertising or through encountering Black people in these spaces. As someone who studies hunting, I know that in the States there is an organization called the National Brotherhood of Hunters, it’s all Black hunters. I would love to see more Black people hunting. Especially in Canada, the majority of the Black population lives in urban centers. It’s not that Black farmers and Black hunters and Black cowboys don’t exist, but there’s kind of been this erasure of those people in those communities in literature and media. When is the last time you read a cowboy novel about a Black boy? Probably never, so I think marketing does have a huge part to play in that regard of reversing that erasure of Black people whether farming the land or enjoying the outdoors.

Rhiannon Kirton visiting Bison Quest Wildlife Vacations in Montana courtesy of biologists Dr. Craig Knowles and Pam Knowles. Credit: Dr. Craig Knowles