Pangolins could go extinct before most people even know they exist. Image taken by Maria Diekmann.

Pangolins are in crisis, with all eight species threatened with extinction. This means that an entire taxonomic Order, the Pholidota, faces going the way of the dodo. Fortunately, pangolins are starting to receive the attention and conservation action that they deserve and there is cause for optimism.

Pangolins are truly unique. There are no other species quite like them in the animal kingdom. They are the world’s only truly scaly mammals, being covered in hundreds of individual scales comprised of keratin – similar to our hair or fingernails. Despite their uniqueness, we do not know a lot about them. The few things we do know are that they are characteristically shy, solitary and primarily nocturnal, and endearingly, roll up into an impregnable ball when threatened. Of the eight extant species, four occur in sub-Saharan Africa and four inhabit parts of Asia, from Pakistan to China and the Philippines.

Despite little knowledge of the animals, pangolins have been consumed by man throughout history and overexploitation is the main threat to the species. The Bornean Giant Pangolin (Manis paleojavanica) went extinct about 40,000 years ago, likely as a result of overexploitation following the arrival of humans, and pangolin populations in many parts of the world are facing the same threat today. For instance, estimates from China suggest populations there have been reduced by 94% since the 1960s. Pangolin meat has been and is still eaten as a local source of protein across Africa and Asia and is also consumed as a luxury good in parts of Asia. Pangolin scales have been used for endless applications, in particular as an ingredient in traditional Asian medicine to purportedly treat a variety of ailments, which continues today. Pangolin skins were also traded in the hundreds of thousands between the 1970s and 1990s, primarily to the U.S and Mexico, for the manufacture and retail of leather goods including belts, boots and handbags.

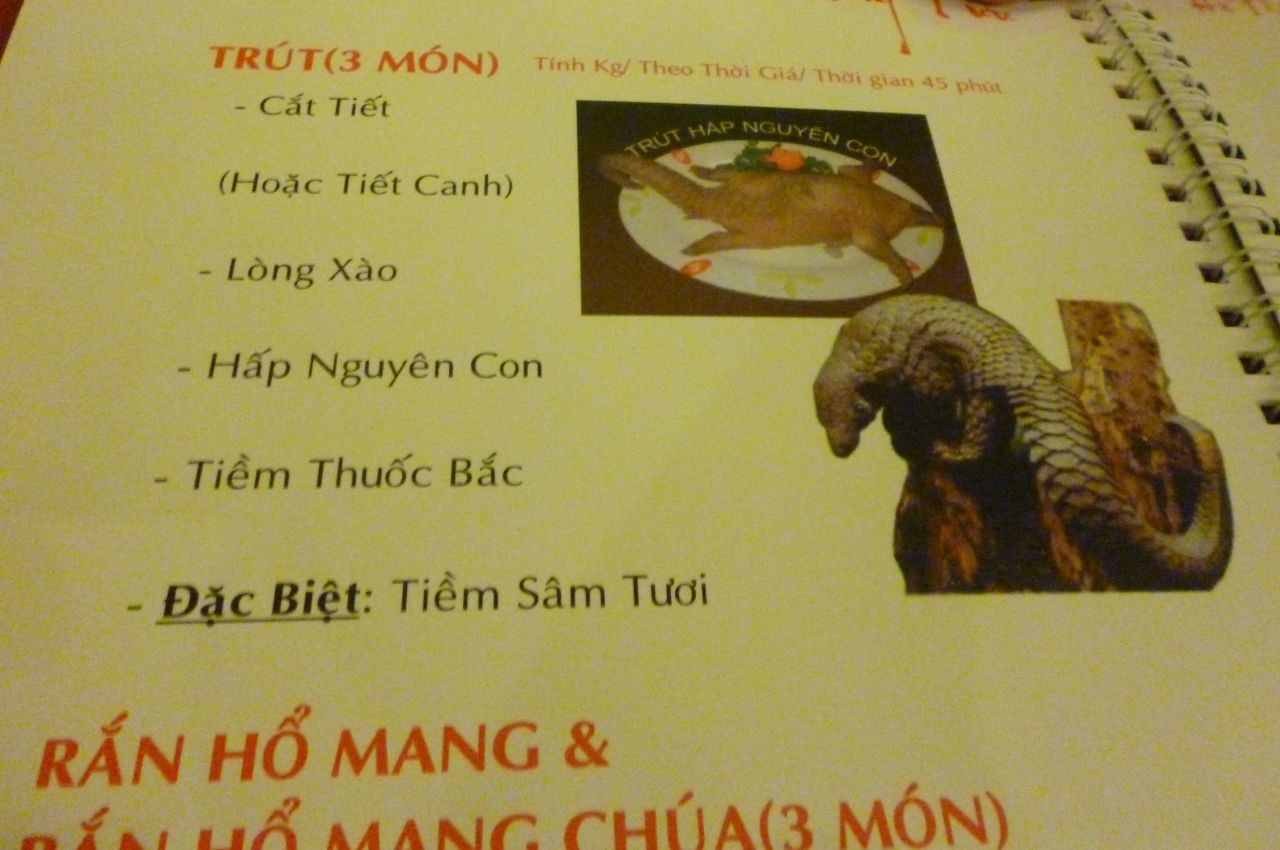

Pangolin cooked 6 different ways on a menu in Vietnam. Image taken by Dan Challender.

This exploitation has occurred despite measures designed to protect pangolins. For example, the Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica) received protection under Indonesian legislation as early as 1931. Similarly, Asian pangolins were listed in CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) Appendix II in 1975, meaning international commercial trade in the species was permitted only where it was not detrimental to wild populations. However, large volumes of trade in skins and scales took place in subsequent decades and while it may have been declared legal, evidence suggests that it was biologically unsustainable. This trade was dwarfed by a simultaneous illegal trade, especially in scales, to countries including China and the Republic of Korea. Consequently, in the year 2000 CITES took additional measures, introducing zero export quotas for Asian pangolins traded commercially, in effect, a proxy trade ban.

The Sunda pangolin – now critically endangered, populations are thought to have fallen by up to 80% in the last couple of decades. Image taken by Dan Challender.

However, the situation has gotten worse. Since the year 2000, it is estimated that more than 1 million pangolins have been poached from the wild and trafficked globally. Much of this illegal trade has been destined for China and Vietnam and largely involved the meat and scales of the Sunda Pangolin, which is native to Southeast Asia. Yet in the last decade an even more worrying trend has emerged, the development of intercontinental trafficking of African pangolin scales to Asian markets.

Having first come to light in 2008, international smuggling of African pangolins now takes place on an industrial scale. In 2016 CITES listed all eight species of pangolin in Appendix I, granting pangolins the strictest form of protection and banning all international commercial trade. Despite this, in 2017 there were numerous major shipments of African pangolin scales seized in China, Hong Kong and Malaysia, involving an estimated 100,000 African pangolins. The largest of these shipments weighed 12 tonnes and was the biggest single seizure of pangolin scales ever recorded.

In recent years, 80% of pangolin scales confiscated from the global black market are from African animals. Image taken by TRAFFIC.

Given the complexity and dynamics of pangolin trafficking, saving the animals from extinction will require a multi-pronged approach. The enforcement of applicable laws by well-resourced enforcement agencies is critically important, both at the site level and along trafficking routes, as is appropriate legislation, and countries are making changes to ensure that pangolins have the necessary levels of protection. For example, the state of Sabah in Malaysia recently revised its legislation meaning the Sunda Pangolin is now listed as ‘Totally Protected’, the highest form of protection available. Nevertheless, legislation inherently discounts the social, economic and cultural drivers of wildlife trafficking, and a range of additional interventions are needed. These efforts include working with local communities and indigenous peoples that live alongside pangolins to help secure populations, and efforts to change consumer behaviour in order to reduce demand for pangolin parts.

Trying to change the way customers behave in order to reduce demand for wildlife products is a relatively new concept in conservation, and determining how to actually change consumer behaviour away from specific wildlife products is challenging. Current thinking suggests that it can be done by gaining an in-depth understanding of consumers and their motivations, influences and influencers, and by conveying the correct message through the most appropriate means of communication to alter future behaviour. One commonly used tool is to secure the support of celebrities, Jackie Chan for example, to act as the messenger, but we have yet to see how effective this method will be. Changing consumer behaviour is arguably more challenging for pangolins than other species because they are in demand for both their meat and scales. Today meat consumption in China and Vietnam occurs in high-end restaurants adorned with luxury brands and occurs in part, to reinforce social status among consumers and their peers and business associates. It also involves bringing pangolins into restaurants live and killing them in front of consumers, something I’ve been unfortunate enough to witness, but which remains socially acceptable in key markets. Similarly, pangolin scales are used in medicines which reportedly help lactating women secrete milk and which poses its own set of challenges and ethical considerations.

Pangolin scales have been used in Traditional Asian Medicines for centuries but today the demand for pangolin products is driving these creatures to extinction. Image taken by TRAFFIC.

Despite such challenges, there is cause for optimism. The profile of pangolins has increased enormously in recent years as concern for the fate of the species has grown. While a few years ago pangolins would have been described as forgotten species, they are now increasingly iconic. This, in turn, has led to greater attention from governments, NGOs, civil society organisations and conservation scientists, and an increase in much needed funding support for conservation action. Encouragingly, following the publication of the first ever global conservation strategy for pangolins in 2014, ‘Scaling up Pangolin Conservation’ a number of pangolin range states have demonstrated leadership by developing national strategies for the species, and through the IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group, I’ve been proud to help develop such strategies. Examples include Singapore, Taiwan (P.R China) and the Philippines among others. Additionally, there is now a multitude of organizations working to conserve pangolins across Africa and Asia (some projects can be found here) by supporting law enforcement efforts, researching demand for pangolin products, working with local communities and indigenous peoples groups, rescuing, rehabilitating and releasing trade-confiscated animals and by conducting much needed research on the species to improve our knowledge and understanding of them to inform conservation action.

The profile of pangolins has increased enormously in recent years as concern for the fate of the species’ has grown. Image by Victoria Bromley

Nature: The World’s Most Wanted Animal premieres Wednesday, May 23 at 8 pm on PBS (check local listings).

Editor’s note: This article was originally posted on the BBC in conjunction with the British premiere of “The World’s Most Wanted Animal.”