Spy Gorilla nestled in the ferns of Uganda. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

Shrouded by ferns, baby Spy Gorilla, is perfectly positioned to observe the elusive wild mountain gorillas of Uganda. Outfitted with a 4K camera in one eye, the robotic spy creature takes in the lush jungle surroundings as the morning mist clears and a troop of gorillas appear. As they observe this new arrival there is tension in the air, yet an infant gorilla is immediately interested in “playing” with the spy. The leader of the troop, a silverback mountain gorilla, moves cautiously towards the juvenile newcomer. The great silverback thrusts his arm out to keep the rest of the group away while he evaluates. Spy Gorilla will not be welcomed to this close-knit family without his approval. The final test: the mighty silverback stares into the animatronic eyes of Spy Gorilla. His face is mere inches from the camera, allowing Spy Gorilla to record all of his complex facial expressions and vocalizations, and relay them back to audiences at home. To show respect, Spy Gorilla averts his gaze. This subtle, yet crucial gesture wins over the leader and Spy Gorilla is no longer considered a threat. As the gorillas relax around the spy, they exhibit astounding singing behaviors never before seen on camera.

A troop of mountain gorillas assessing Spy Gorilla. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

The same as above, from Spy Gorilla’s point of view/hidden camera. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

This is just one of countless interactions between Spy in the Wild 2’s “Spy Creatures” and wildlife. What began as a ‘Bouldercam’ to observe lions directly in their den has morphed into an award-winning series pioneered by John Downer Productions, with over 50 realistic spy creatures capable of complex animatronic movements designed to interact with animals in the wild. Equipped with revolutionary remote camera devices, highly realistic physical features, and state of the art microphones, these spies blend seamlessly into their environments and are able to document the secret lives of animals. The interactions between remote operated animals and wildlife are not just enlightening for audiences, but also for scientists and educators who study these animals.

Looking deceptively like a mobile rock, but carrying a hidden digital camera, ‘Bouldercam’ was one of the first spy cams capable of filming animals in the wild. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

One of the many animal experts the Spy team consulted was Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka. Dr. Kalema-Zikusoka has been studying mountain gorillas in Uganda for 25 years. Starting out as a veterinary student in 1994, she became Uganda’s first wildlife veterinary officer, and is now the Founder and CEO of Conservation Through Public Heath (CTPH), an organization dedicated to the co-existence of endangered mountain gorillas, other wildlife, humans, and livestock in Africa. Dr. Kalema-Zikusoka believes Spy Gorilla provided an innovative approach to learn more about these endangered animals.

Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka in the field with Matthew Gordon and cameraman Richard Jones. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

“Footage from Spy in the Wild 2 provided a unique insight into the behavior of mountain gorillas,” Dr. Kalema-Zikusoka said. “It brought out their personalities and showed that they are naturally curious and very intelligent. When the robotic spy baby gorilla was introduced, I was surprised when the adult blackback male gorilla became protective. I was even more amazed when on the next visit the silverback gently moved the other gorillas in his group away so that he could get a closer look at this baby who looked like them, but was clearly not a gorilla. When he accommodated this stranger, the rest of the group went on to take a closer look at the spy gorilla.”

The Spy Creature technology has even been put into practice by penguin researcher Dr. Yvon Le Maho in Antarctica. Emperor penguins have a reputation for being notoriously skittish. When scientists would approach these penguins to collect biological data, including their heart rate, they noticed the penguins would back away and their heart rate would spike. Therefore, a team of international scientists and filmmakers, led by Dr. Yvon Le Maho decided to collaborate to create a remote control rover disguised as a penguin chick to observe the difference in stress levels. Dr. Le Maho and his colleagues measured penguins’ heart rates when the remote penguin rover approached and when a human researcher approached.

“There was a very high increase in heart rate with the human – much more than in a rover,”Dr. Le Maho explained. The results from the study were published in the scientific journal, Nature, and proved to Dr. Le Maho that the undercover approach provided a less invasive and stressful way to collect data on emperor penguins. The emperor penguins and their chicks were so convinced by the undercover penguin chick that they even tried to communicate with the rover using vocalizations, according to Dr. Le Maho.

Spychick investigates Emperor penguin colony. Photo by Frederique Olivier.

“Scientists do not generally speak about the disturbance they cause,” Dr. Le Maho said in an interview about the study. “But I have always been very concerned with that – it relates to both science and ethics.”

Philip Dalton, producer of the Spy in the Wild series, assisted in the scientific collaboration between Dr. Le Maho and John Downer Productions.

Spychick investigates Emperor penguin colony. Dumont D’Urville Station, Antarctica. Photo by Frederique Olivier.

“Yvon picked up on the fact that if you take the human out of the equation and use the spy creature technology to get in close, you can get really good results,” Dalton said. “He was able to quantifiably say that using robots is a far better method than having humans collect data because it does not stress out the birds. That was very satisfying for our team because not only is it a good filming tool, it can be quite a useful tool for scientific purposes as well.”

Investigating wild animals while minimizing human disturbance remains an important methodological challenge for scientists. Covert camera technology is revolutionizing the study of animals, and giving researchers insights that could ultimately help them fight extinction and habitat loss. A recent study revealed using a drone to film hippos in Africa is an effective, affordable tool for researchers to keep track of the threatened species’ population from a safe distance, particularly in remote and aquatic areas. Traditional methods of collecting data on hippos include unreliable aerial surveys and risky land and water surveys, according to researchers at the University of New South Wales.

“Even though hippos are a charismatic megafauna, they are surprisingly understudied, because of how difficult it is to work with nocturnal, amphibious and aggressive animals,” said lead author Victoria Inman, a PhD candidate at UNSW Science.

Animals that are normally aggressive or skittish towards human observers appear inquisitive when they come across Spy in the Wild’s animatronic creatures. Hippos are the world’s deadliest large land mammal, killing an estimated 500 people per year in Africa, according to the BBC. However, when Spy Hippo comes face to face with a dominant bull in Spy in the Wild 2, the remote operated hippo is able to exhibit confidence through ear wiggling, causing the male hippo to let down its guard and even allow it to approach a baby in the river. This acceptance within the hippo herd gives Spy Hippo the chance to document some of the most intimate views of hippos that have ever been seen.

Spy Hippo is able to get up close and personal with the most dangerous animal in Africa. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

“The reaction of the animals to our spies does vary depending on the type of animal we are filming,” Dalton said. “Most animals are very curious at first, they will carefully inspect the spy, often sniffing first. They quickly work out the spy is not a threat or food. That is when they relax and the spy becomes very much part of the scenery. It is at that point we get very interesting behavior, being so close to the animals means we end up filming extraordinary detailed behavior and sound.”

Utilizing the latest technology also helped the Spy in the Wild 2 team ensure that their spy creatures were able to document even more than the first season, according to series producer, Huw Williams.

Philip Dalton with Spy Bald Eagle. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

“The latest camera technology allowed better-stabilized shots, with higher res and aerial technology, which allowed us to explore an array of aerial spies,” Williams said. “We also thought hard about animals that we had not covered in the past and environments that we could really try to tackle. We filmed in the harshest environments around the world, filming in every continent. The second series really reveals behavior never seen before.”

Malcom Beard and Huw Williams with Spy Mobula Ray. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

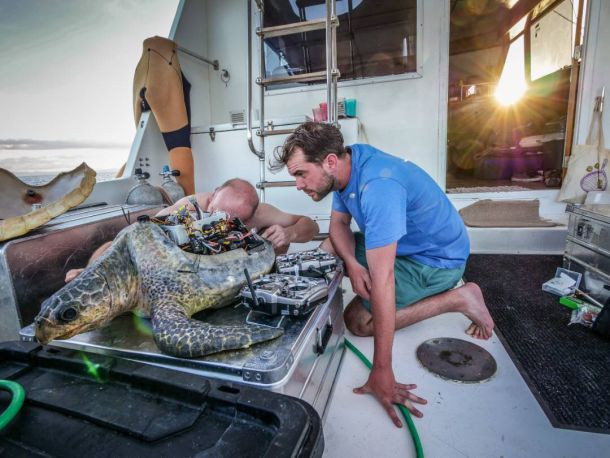

The process of building the spies is complex and varied depending on what animal and behavior the team is trying to film. Series producer, Matthew Gordon worked with Dr. Kalema-Zikusoka on the mountain gorilla sequence to understand which features were most important to focus on.

“For the gorillas, the eyes were extremely important,” Gordon said. “Mountain gorillas learn a lot from each other by staring into each others’ eyes. Therefore, we designed the spy gorilla to be able to close and move his eyes so that when necessary, he could avert his gaze to show respect to the real gorillas. The artists looked at dozens of videos and images of the animals in the wild to make them look as realistic as possible. It’s also about puppeteering. It is important to learn how animals move. We often have professional animatronic engineers come out with us in the field to control the spy creature. The engineer makes the creature move in the most realistic way possible.”

These undercover spy cameras are also able to capture intimate moments that wildlife filmmakers would not be able to acquire through traditional long lens filming techniques, according to Dalton.

“These animatronic robotic camera devices not only mimic the way that the animals look, but also how the animals behave,” Dalton said. “This is a totally different dimension to a wildlife film. As a filmmaker, you’re always looking for innovative ways to capture wildlife behavior. For us, we all believe that the best way to film an animal is by getting the cameras as close to your subject as possible without disrupting their natural behavior. By physically having an undercover camera within inches of an animal captures something quite extraordinary. Because the onboard camera has a wide-angle lens with many microphones you are getting real sound and a wide-angle field of view. Giving you the feeling that you are actually there as opposed to being a passive observer. We know from feedback from viewers who have watched these films, that they are very different because they are able to really engage emotionally with the animals.”

Huw Williams and Malcom Beard with Spy Turtle. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

This emotional engagement with the natural world attracts a completely different demographic to wildlife shows, described Dalton.

“There are a lot of people that would not necessarily want to engage in a wildlife film, but when they see a robotic gorilla or robotic fruit bat filming in the wild, it definitely lures in a new type of audience,” Dalton explained. “Our team does a lot of talks at schools and when we take along our spy creatures it inspires so much interest and excitement within the entire group of kids. You would not necessarily get that same engagement if you did not have your spy creatures as part of that toolkit. For them, they love it and they often go away afterwards, to do their own school projects, building their own spy creatures and deploying them on the school grounds, which brings in another dimension to wildlife film.”

Philip Dalton with Spy Bear. Photo courtesy of John Downer Productions.

In addition to educating and inspiring the next generation with their wildlife programs, the Spy in the Wild characters have been a source of environmental optimism. In 2017, Spy Orangutan, better known as “Biruté” was invited to Washington D.C. to participate in the Earth Optimism Summit. Through the unique lens of Biruté, summit attendees witnessed the wonder of the natural world.

Spy Orangutan, better known as Biruté. Photo by Steve Downer.

“There are so many amazing global conservation projects that are doing good things and reversing problems and getting good results,” Dalton said. “There is actually quite a lot to be optimistic about and that’s what this summit was about. It was looking at innovative research and success stories to try to buoy people up into saying: ‘Look, it’s still worth getting actively involved and coming up with fresh interesting ideas to change the world.”

So what is next on the horizon for the Spy in the Wild team?

“I’m really interested in communicating with animals,” Dalton said. “It would be great to be able to interact with an animal that somehow illuminates to us as humans their intelligence and their ability to communicate through their language. I would like to be able to have a spy creature that can somehow accomplish this. I am a great believer that we have so much in common with animals. We are more connected than we think we are, and animals are definitely more intelligent and complex than we could ever imagine. I do not quite know how we would do it, but we have got a few ideas. I’m already talking with a few scientists that specialize in animal communications to see what we could do to try and tap into that.”