The Mexican Gray Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi). Credit: Jim Clark/USFWS

The Mexican gray wolf is lucky to be alive; it came as close to extinction as possible without vanishing, in the 1970s. But doubts remain about its survival. In November, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released a recovery plan to outline a path forward. Yet the plan was condemned by many who don’t think it provides enough protections for the wolves and also by those who say it does too much. It has also elicited two lawsuits against the agency by environmental groups.

But let’s back up. The Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), or “el lobo”, was originally prevalent throughout Mexico and parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and west Texas. The most genetically distinct subspecies of the gray wolf, it is slightly smaller than its more widespread cousin, and distinguished by a mottled gray and brownish-red coat. In the 19th and especially the early to mid-20th century, government entities declared the Mexican gray wolf a public enemy and the federal government paid hunters to trap and poison the animals. In 1950, with U.S. populations essentially eradicated, the killing campaign extended into Mexico and by the 1970s the wolves were nearly extinct in the wild.

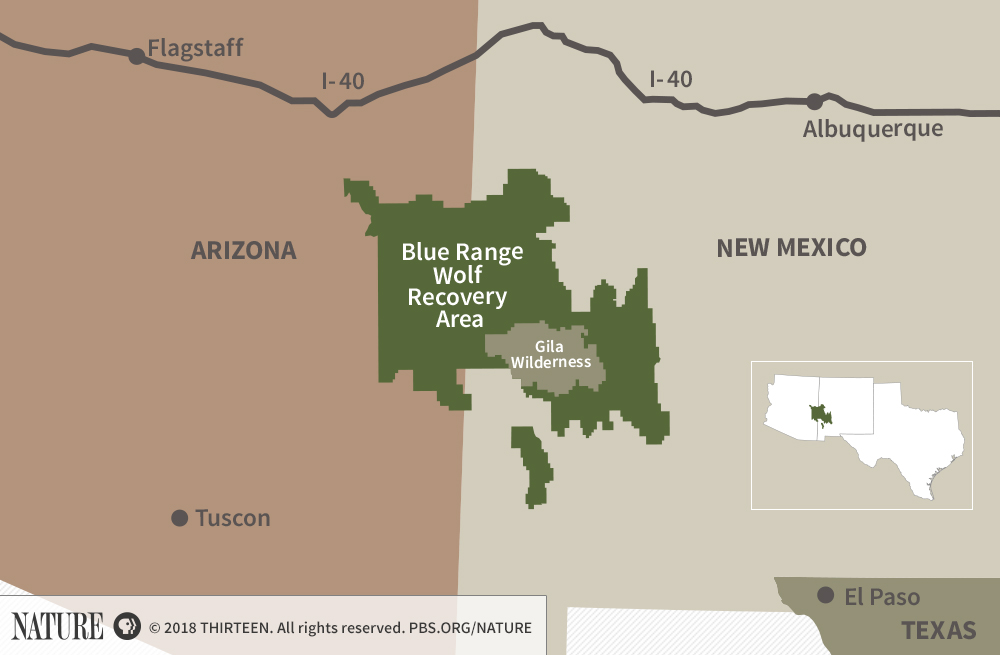

Just in time, public sentiment and political winds shifted, and in 1973 President Richard Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act. Three years later the Mexican wolf was listed. The Fish and Wildlife Service hired a trapper named Roy McBride in the late 70s to capture any lobos he could find alive in Mexico and bring them back safely. An extensive search turned up four males and a pregnant female. Watchful researchers bred these animals with a handful found in Mexican and American zoos, and the captive population of the wolves steadily increased. In 1998, 11 wolves were reintroduced into the Apache and Gila National Forests respectively in Arizona and New Mexico. (This region straddles the border of the two states and was then called the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area.)

The wolves have multiplied, and at last count there were at least 143 in the wild, with 113 in the Blue Range vicinity and another 31 in Mexico. A total of about 240 wolves also live in captive-breeding facilities in the United States and Mexico. The Fish and Wildlife Service is currently conducting a census to come up with a new population estimate, which is expected to be higher.

On Nov. 29, the Fish and Wildlife Service released the Mexican gray wolf recovery plan. Under the scheme, the agency would delist the animal once populations reach an annual average of about 320 individuals in the Arizona-New Mexico population, and 200 in Mexico. The service expects that it will take as much as 35 years to get the animal to a point of recovery and delisting, and cost nearly $180 million. The plan provides for the release of 70 wolves from captivity over this time period, which should help improve genetic diversity. That’s important, since Mexican gray wolves have very low levels of gene diversity; every animal alive today is descended from seven individuals captured in the wild between the 1950s and 1980.

“Mexican wolves are on the road to recovery in the Southwest thanks to the cooperation, flexibility and hard work of our partners,” said Amy Lueders, Southwest regional director of the agency, in a statement. “States, tribes, landowners, conservation groups, the captive breeding facilities, federal agencies and citizens of the Southwest can be proud of their roles in saving this sentinel of wilderness.”

But Arizona Republican Senator Jeff Flake disagreed, calling the plan “yet another federal regulatory nightmare for ranchers and Arizona’s rural communities” in a statement released the same day as the plan. He also characterized it as a waste of taxpayer money. In early January, Flake introduced a bill that would strip the wolves’ endangered status if the federal government determines there are more than 100 animals in the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area that straddles Arizona and New Mexico. That’s almost certain to be the case, as the population has grown since the last estimate, according to ongoing monitoring efforts.

Meanwhile, many environmentalists and wolf advocates say the plan ignores or distorts the science. Geneticist Richard Fredrickson wrote in a formal letter to the agency that the population viability estimate used by the service is not scientifically valid, but rather works backward from the number of wolves that was palatable to politicians in the Four Corners states (Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado) .

“Politics has trumped science from start to finish in this process,” Fredrickson says, “no pun intended with regard to the current administration.”

He specifies that the scientific assessment contained within the current report overestimates the percentage of female wolves that are likely to breed, and underestimates mortality rates, which paints an overly rosy portrait for the animal’s future.

Fredrickson was a member of the scientific team that worked with the wildlife service in 2012, which calculated that for a population of Mexican gray wolves to be viable in the long term, it would have to number at least 750. Further, the populations would have to be geographically separated into populations consisting of a minimum of 200 wolves each, and they generally agreed wolves should be allowed to cross north of Interstate 40, a major thoroughfare that cuts through northern Arizona and New Mexico. But the agency didn’t move forward with a plan based on these recommendations. Under the current rules, wolves lose many of their protections when they stray outside of places where they have been released, such as Gila National Forest in New Mexico.

The science group’s recommendation suggested that for enough diversity to be reclaimed, the population should be allowed to grow bigger. Michael Robinson, a conservation advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity, argues there should be more reintroductions. It would also be better to release captive-bred family groups into the wild, which would increase the survivorship of the animals, he says. Currently, wolves are released as pups, and placed into the dens of other wolves that have recently given birth, but this process is labor-intensive and doesn’t have a high survival rate, he adds.

“I have to say things don’t look so good for Mexican gray wolves at the moment,” Robinson says.

John Bradley, a spokesman for the Fish and Wildlife service, said that the plan is based on the best available science, but didn’t immediately respond to questions about these claims.

Under the plan, wolves that prey upon cattle may be tracked down and killed. The animals are also illegally shot at an average rate of about one every other month. One study published in October 2017 in the Journal of Mammalogy found that official estimates underestimate the risk of mortality from poaching.

Ranching groups also dislike the plan, but for different reasons. “The latest version of the recovery plan goes far beyond recovery,” says Patrick Bray, executive vice president of the Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association. He said he doesn’t buy arguments that genetic diversity is a real challenge for the animals. He expects their numbers to keep growing, and wolves to continue preying upon cattle.

In the U.S., the wolves mainly eat elk, which make up about 80 percent of their diet. But they do sometimes eat cows. This is especially a problem in Mexico, where there aren’t large tracts of public land, and there are fewer prey animals, and no elk. One 2006 study found that cattle made up eight percent of the American wolves’ diet, while a 2009 paper put that figure at 17 percent. (They also eat white-tailed deer, mule deer, rabbits, javelina, and other small mammals.) To prevent the predators from killing and eating cattle, the agency places food near the dens of wolves that are raising pups.

Ranchers can be reimbursed by the government when their animals are taken by wolves. But Bray says those payments don’t include indirect costs associated with wolves, such as time and effort dealing with the predators. The money “pays for that calf, but we’re not in the business of killing our animals. We are in the business of being stewards of the land, raising a quality product and getting them to market,” he says.

Not everyone is upset by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife plan. The Albuquerque Journal Editorial Board, for example, which tends to take a conservative viewpoint, said it “strikes a blow for reason and compromise… and the hope of a new relationship that values both ranchers and wolves.” Meanwhile, the battle plays out in the courts. There are several legal cases about finer points of Mexican gray wolf recovery pending right now, and due to conclude soon. And last Tuesday (Jan. 30), two coalitions of environmental groups filed two separate lawsuits against the Fish and Wildlife Service, saying that the recovery plan violates the Endangered Species Act and won’t allow the animals to sufficiently recover. Legally speaking, there’s no end to the conflict in sight.