Credit: Eric R. Olson/NATURE

From the tall grass savanna of Kenya to the forested slopes of the Rockies, from the steaming jungles of Indonesia and the crags of the Himalayas to your very own living room, cats prowl our planet. Some are large and imposing, celebrated for their predatory power. Others are small and elusive, their spots blending into the shadows. Not to mention our familiar moggie companions that purr and yowl for a tender back scratch. At whatever size, and whatever form, we seem to have limitless adoration and fascination for the felines that inhabit our planet. Our affection for them runs so deep that we’re even transfixed by those that slipped into extinction long ago. There is no more potent symbol of the Ice Age than Smilodon fatalis, the great saber-toothed cat preserved by the hundreds in the thick muck of the La Brea asphalt seeps. Living or dead, we love cats.

But where did cats come from? They did not spontaneously burst from the grass to ambush their prey. The world’s cats, both large and small, wild and domestic, have as deep and circuitous an evolutionary history as any other species. And while they’re all consummate predators, the cat family has taken a variety of forms. Their remarkable flexibility has allowed them to flourish, whether in the shape of lanky speed demons like cheetahs or the extinct sabercats who stalked baby mastodons, or domestic tabbies that are the scourge of backyard wildlife. Cats have always been malleable beasts, changing with the shifts in climate and habitat that the Earth has undergone since their origin over 25 million years ago. And while there are various points at which we could start the great cat tale, let’s begin with one of the worst days in the planet’s history.

Up from the Ashes

About 66 million years ago, on a Cretaceous day just like any other, a six-mile-wide chunk of rock hurtled through the atmosphere to strike the area we now know as the Yucatan Peninsula. The devastation was unprecedented. Tsunamis emanated outwards from the impact site, ripping up the seafloor and crashing far inland along North America’s southern coastlines. It took hours before the fragments of rock and other debris thrown into the atmosphere by the massive blast hurtled back down towards the planet’s surface. The friction from the reentry was so great that these pieces heated the atmosphere intensely, turning the air into an oven that ignited massive wildfires all over the planet. And somehow this was not even the worst of it. In the months and years following the impact, a thick cloud of dust and debris blotted out the sun. Temperatures fell and vegetation withered. The non-avian dinosaurs, which had dominated ecosystems on land for over 130 million years, all perished. Only birds remained to carry on the dinosaurian legacy. The flying pterosaurs, seagoing lizards called mosasaurs, coil-shelled ammonites, and other forms of life were wiped out too. And even groups of animals that pulled through – such as lizards and mammals – had their own numbers severely cut back. All told, about 75 percent of known species disappeared practically overnight. But as devastating as this environmental catastrophe was to the life on our planet, without it, there wouldn’t have been any cats.

A protoypical miacid, an early ancestor of cats. | Credit: EvelynKirkaldyArt.com

Mammals had thrived during the Age of Dinosaurs, but only at a small size. There were ancient equivalents of aardvarks and badgers and flying squirrels and raccoons and beavers, but nothing like a cat. It took an asteroid shaking up the world’s ecosystems for mammals to flourish in ways they never had before, proliferating in a warm, lush world free of gigantic reptiles. This is the setting in which the meek evolutionary twig that supported the ancestors of cats first emerged. Paleontologists know these mammals as miacids. If you were able to see them today, they might remind you of something like a civet or a pine marten – small and slender mammals that chased down lizards and smaller mammals through the ancient undergrowth. They were not the prime carnivores of their time. That title went to archaic and totally extinct groups such as the creodonts – burly predators that superficially resembled the cats and hyenas that would come later – and mesonychids, nicknamed “wolves with hooves.” The miacids stayed small as long as these larger predators were on the prowl, but by about 42 million years ago the miacids sprouted off a new branch of their own. This offshoot was the Carnivora, the group to which dogs and cats and bears and seals and civets all belong. This was a new kind of predator, equipped with specialized teeth capable of efficiently shearing through flesh. After another 12 million years, it was this group that would give rise to the very first cats.

The ‘First Cat’

Exactly what the founder of the cat family looked like is unknown. The fossil record, as Charles Darwin once wrote, is like a stone book for which we only have a few words or sentences in an incomplete array of chapters. This makes it all the more difficult to pin down precise ancestors, especially the further back in time you go. Therefore paleontologists look for animals that have what they call transitional features – traits that bridge gaps between groups and act as proxies for those ancestors, tracing the chaotic route of evolution from the present way back into the past. For cats, that search has led fossil experts to a little mammal called Proailurus. The naturalist Henri Filhol named this extinct beast back in 1879 from fossils found in France, and even then he could tell that the mammal had something to do with the origin of felines: Proailurus means “first cat.”

Not that Proailurus looked very much like the cats we know today. This 30 million-year-old mammal, which was about the size of the friendly purrbox that might inhabit your own home, still looked something like a mongoose or civet, using its retractable claws to clamber up and around trees. Nevertheless, the arrangement of the wee carnivore’s teeth, as well as other anatomical clues, have led paleontologists to place it very close to the origin of cats. It represents the time when cats split off from the ancestors of hyenas and other members of the Carnivora family tree. From there, though, we need to make a bit of a jump. The fossil record of cats during this time is relatively sparse, and the next prehistoric star in the lineup paleontologists point to is Pseudaelurus. This was more of a modern-looking cat, which had evolved about 20 million years ago. These cats still had a proportionally longer spine than modern species, and you can still see remnants of the additional teeth that were lost as cats evolved to shear flesh with their cheek teeth. This lynx-sized feline basically represents the standard cat body plan that would proliferate across the planet for the next 20 million years. Even Pseudaelurus itself wandered from Europe to Asia and North America, giving cats a claw hold across the northern hemisphere.

Rise of the Swordtooth

After the time of Pseudaelurus, however, cats hit a fork in the evolutionary road. Two different cat groups diverged from each other, spinning off different forms. There was the Felidae – the relatives and predecessors of today’s cats with conical teeth like leopards and cougars – and the long-toothed Machairodontinae, or sabercats. The long-toothed group were not, as they are popularly known, “sabertoothed tigers.” The ancestors of tigers and sabercats split from each other over 20 million years ago and are about as distantly related from each other as a red fox is from a wolf. And speaking of sabercats, not every cat-like mammal with long fangs can claim membership in the famous sabercat line. In the broader carnivoran family tree, there were at least two other cat-like groups of mammals that independently evolved long saber fangs – predators called nimravids and barbourofelids – that were cousins of cats but fell outside the cat group proper. Even marsupials tried to get in on the act. In South America, there was a marsupial predator called Thylacosmilus – the pouch knife – with excessively long canines that slotted into flanges of bone jutting down from its lower jaw. Saberteeth evolved over and over and over again in the history of mammals. In fact, it’s strange that there aren’t any sabertoothed predators alive today. But in the history of cats, the sabercats were a group to themselves and included some of the most fearsome predators of all time.

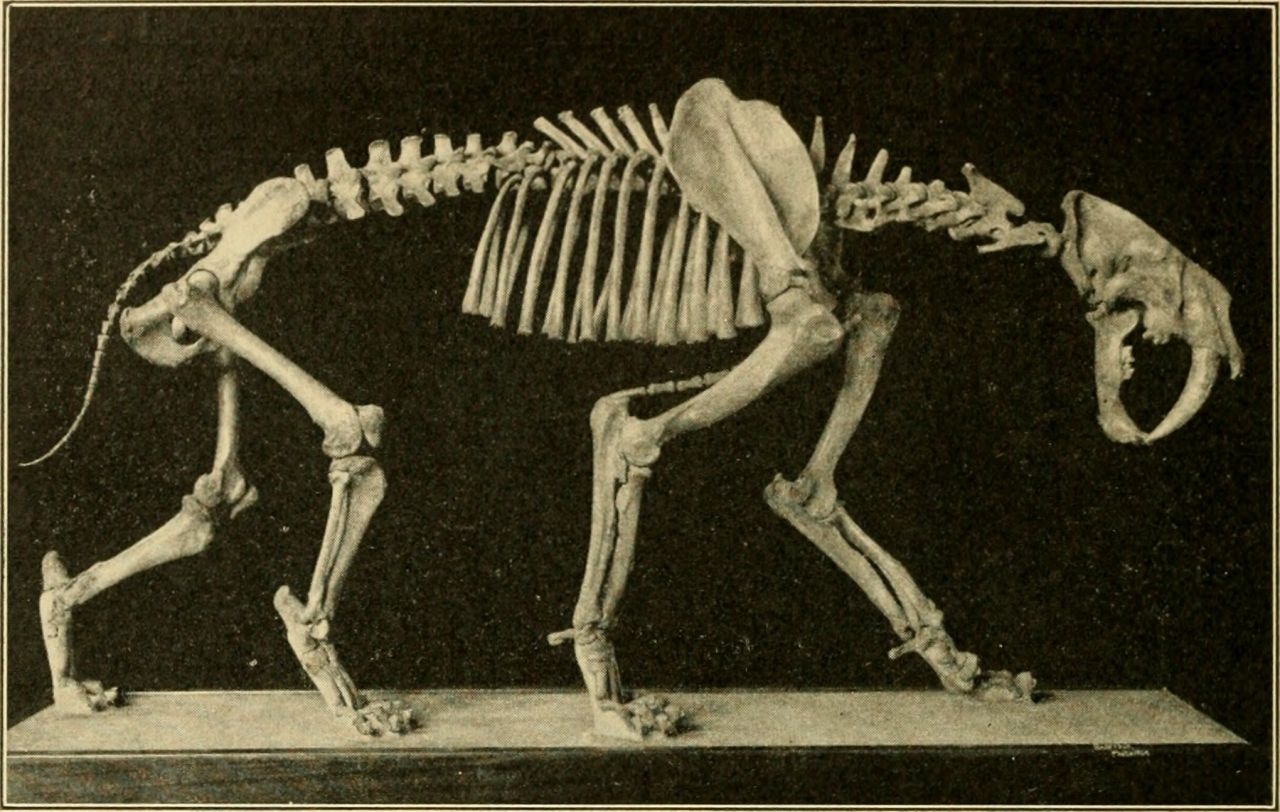

A 20th century reconstruction of Smilodon, the great sabertoothed cat. | Credit: The Prelinger Archive

Not all sabercats were exactly alike. One of the earliest, the 15-million-year-old Paramachairodus from Europe, was about the size of a leopard and had relatively short canines compared to its later relatives. Much closer to us in time, from 2.5 million years ago to about 10,000 years ago, the famous Smilodon line had species that exceeded a Siberian tiger in size and grappled prey to the ground with burly forelimbs. The much more slender Homotherium had shorter canines and a rangier build better suited for running after victims. Then there was Xenosmilus – the “alien knife” – who mixed short, broad sabers with a muscular build, mixing and matching traits seen in the Smilodon and Homotherium lines. There were many ways to be a sabercat.

Those fearsome teeth have long had a hold on our imagination. So much so that there’s been no shortage of ideas about how sabercats used their fangs. Over the years these cats have been cast as stabbers, armor-piercers, and even blood-suckers, but the modern consensus is that Smilodon and its relatives used their extended canines to slice through the soft parts of their ancient prey. A sabertoothed bite to the neck or belly of a victim would have caused catastrophic blood loss, if not immediate death.

The last of the sabercats died out about 8,000 years ago. Why they disappeared is a mystery. While art works, museum displays, and movies have often depicted the cats trying to take down giant sloths and mammoths, recent studies have suggested sabercats preferred mid-sized prey such as camels and baby mastodons. Still, it seems that these cats specialized in hunting the megafauna that once flourished during the last Ice Age, and when many of these creatures died, so did the cats. For the first time in over 20 million years there were no more sabercats, although, given how many times they’ve evolved, it’s likely that something resembling Smilodon could eventually evolve again. For now, though, the world belongs to the short-fanged cats.

The Felids We Know — and Love

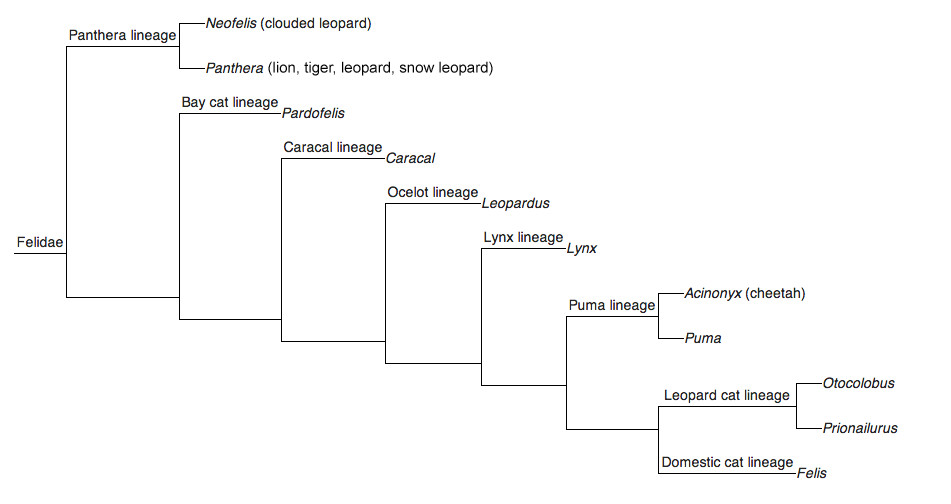

All the cats we know today – from the biggest Siberian tiger of the frigid forests to the tiny margay of the American tropics – are felids. They split from the sabercats over 20 million years ago, and today represent about 40 distinct species spread across the Americas, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Of all the wild cats, though, it’s the big cats that get the lion’s share of our attention. Despite sharing a large body size, though, not all “big cats” are close relatives. There are two subdivisions of living cats. One group, the Pantherinae, includes tigers, lions, jaguars, leopards, and snow leopards, as well as the smaller clouded leopards (the most ancient lineage of the pantherine group). A second group – the Felinae – includes cheetahs and cougars in addition to the comparatively diminutive fishing cats, sand cats, jaguarundis, and their relatives. The cat family tree is a tangle of surprising connections.

The felid lineage. | Source: Wikipedia.org

In terms of the world’s beloved big cats, though, paleontologists have recently started to zero in on where they came from. In 2013, paleontologists working in Tibet announced the discovery of Panthera blytheae. Up until the cat’s discovery, the oldest known pantherine cats were thought to be from the 3.6 million year old bedrock of Tanzania. Panthera blytheae moved back the group’s origins to older than 4.4 million years, and in a place that wasn’t expected. Big cats were thought to have originated in Africa, but the recent discovery seems to point to Asia, and, more specifically, the Tibetan Plateau. Other mammals – such as woolly rhinos and Himalayan blue sheep – seem to have gotten their start in the same place, leading paleontologists to suggest that mammals whoevolved in this chilly place developed adaptations for cooler conditions, which allowed them to spread outward and thrive as the planet started to go through the ebb and flow of Ice Ages. This doesn’t mean that Panthera blytheae was the direct ancestor of today’s lions and tigers, but the cat points to a deeper and more complex story for our favorite carnivores than anyone previously knew.

Of course, there’s more to cat evolution than the backstories of fierce sabercats or lions teaming up to take down water buffalo. Many of us live with cats. The ASPCA estimates that there are between 74 and 96 million domestic cats in American households alone. That number even outstrips the count for dogs ‑ our supposed ‘best friends’. You may even be feeling the rumble of your feline companion’s purr on your lap as you read this. How did this special connection between our species and a fuzzy carnivore with sharp teeth and retractable claws come to be?

Entire books have been written about how humans and dogs became companions, but the details of how cats sauntered into our daily lives is much more obscure. There was no great accord or historical marker to identify the date for us. But biologists and archaeologists have been able to suss out a few key details. Perhaps not surprising to cat owners, it appears that cats adopted us rather than the other way around. A widely-reported study from 2007 suggests that the ancestors of domestic cats were the Near Eastern wildcats of the Fertile Crescent. Sometime around 10,000 years ago – a time, it should be noted, when sabercats and other Ice Age cats like the cave lion were still alive – some of these cats decided to take up with the human inhabitants of the area. Humans probably had little to do with the domestication. But by settling down, farming, and storing our food, people created a smorgasbord for rodents that, in turn, enticed cats to wander into our homesteads. The felines proved themselves useful enough that we let the cats settle down with us, and, honestly, who could resist the mewing charm of little kittens?

Our inadvertent partnership with cats changed them just as they changed our daily lives. Biologists have even been able to see this in cat genes. On the surface, the feline that struts around your home doesn’t seem much different from their wild counterparts. (This is part of what makes feral cats such an ecological nightmare – they’re adept hunters of native species that has led countries like Australia from banning outdoor cats.) But get down into the DNA and biologists can see that our favorite pets show at least 13 genetic markers that distinguish domestic breeds from wild ones. Some of these differences are associated with behavior, such as changes in when cats feel fear or how they’re able to learn when provided food as a reward, showing how their brains changed as they came in to settle down with us.

Looking back at our own history, it may seem a little strange that we keep cats so close to us. The very first humans evolved in Africa over six million years ago, and by then there was a wide array of sabertoothed and non-sabertoothed cats on the scene. Some human fossils – such as the skull of one of our australopithecine cousins dubbed SK-54 with two puncture marks matching the tooth width of a leopard – indicate that cats even ate some of our relatives. Coming down from the trees meant that we were entering a world ruled by cats ready to pounce from the grass. We evolved alongside cats, undoubtedly fearful as well as fascinated. For while each cat species differs, they all share elements of the same grace and charm we’ve admired for as long as human memory can trace back. Through our own history we’ve been cat food, stolen their kills, admired them from afar, treated them as gods, and, unfortunately, brought far too many to the brink of extinction. If we truly love cats as much as our culture professes we do, then the best we can do to honor them is let cats continue their 30 million year evolutionary journey into the future.