Florida panthers need space and in a state of busy roads and sprawling development, finding that space grows harder every day.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

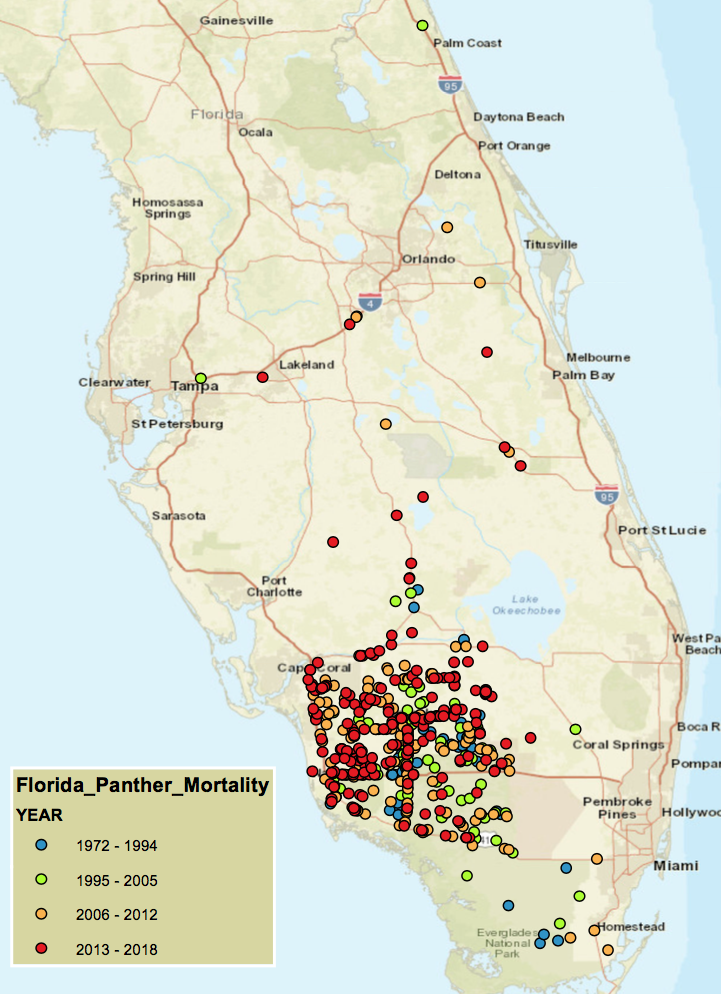

These endangered animals, with a population estimated at between 120 and 230, prowl less than 5 percent of their historic range. The wild cats suffer from isolation, loss of habitat – and roadkill. A male panther’s hunting and breeding territory typically covers 200 square miles, a female’s home range, 75 square miles. That equals a lot of wandering and much crossing of roads. In 2018, vehicles killed at least 25 Florida panthers and in 2017, at least 24.

A team including the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), US Fish and Wildlife Service, Florida Department of Transportation and other partners have long worked to reduce these numbers. Beginning in the 1980s, with the creation of Interstate 75 running east-west between Naples and Ft. Lauderdale, the partners began installing wildlife crossings, typically passages under bridges with barrier fencing to direct animals away from the road and to the passages. Currently, a total of 60 wildlife crossings or bridges and fencing installed in key areas, mostly along I-75 and the north-south State Road 29, have sharply reduced panther mortalities nearby. The team has identified five hotspots – stretches of road where nine or more panthers have been killed – in need of additional crossings.

“They have a pretty solid protocol for where to put crossings,” said Wendy Mathews, conservation projects manager for The Nature Conservancy in Florida. But a critical element, she added, is providing corridors for the cats to travel between protected habitat. The organization has helped secure corridors and habitat for panthers in Okaloacoochee Slough, Big Cypress National Preserve, Everglades National Park, the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge and, most recently, near the Caloosahatchee River, currently the northern limit of panther territory.

Mathews points out that crossings have been documented as successful, at least when properly designed and placed. Researchers who analyzed dozens of studies around the world found that fences, with or without crossings, reduced roadkill of large mammals by 83 percent. Animal detection systems, which flash lights to warn motorists when an animal trips a light beam on the roadside, are less expensive but also less effective, reducing large mammal deaths by 57 percent. Drivers also may become habituated over time to these systems.

The roadkill problem is hardly unique to panthers; according to the Federal Highway Administration, an estimated one million to two million collisions between cars and large animals, such as deer or moose, occur each year in the US. That doesn’t count small animals such as raccoons, armadillos and skunks, and at least one study suggests the actual number may be six times greater when taking into account removal of roadkill by scavengers. In the US, vehicle collisions are a serious threat for at least 20 endangered or threatened species in addition to the panthers.

For the species to continue to recover, Florida panthers need to not only survive crossing roads, but also must establish breeding populations north of the Caloosahatchee. A mother and kittens appeared north of the river in early 2017, the first such sighting in more than 40 years, and TNC is working to cobble together protected landscapes and connections stretching from the river into central and northern Florida.

Any cats heading north face another formidable obstacle, though: Interstate 4. To help them overcome it, wildlife crossings need to move north as well.