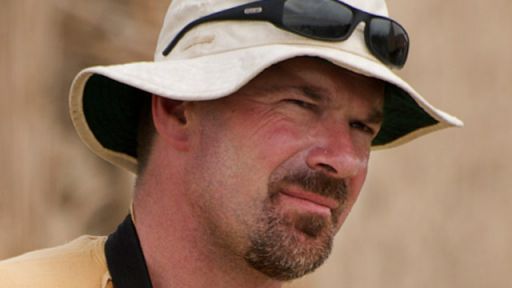

Azzam Alwash stands at the center of an enormous project to re-establish Iraq’s unique wetlands. An Iraqi-born trained civil engineer, Azzam grew up in the town of Nasriyah, on the banks of the Euphrates. As a boy he accompanied his father, a government water engineer, on many trips into the marshes.

Azzam resettled in the U.S. well before Saddam Hussein drained the marshes, but returned to Iraq with his wife Suzie to lead the monumental effort to restore the Iraqi wetlands.

How did you first get involved with this remarkable restoration project?

My work on behalf of the marshes started in 1997/1998 in trying to put the spotlight on what Saddam did to destroy the marshes and the use of water (or lack thereof) as a weapon of mass destruction. Not many people paid attention to what my wife Suzie and I were saying at the time, and our effort consisted of me going around to scientific conventions and Iraqi opposition meetings with a presentation about the marshes and how important it is and what a crime it is that it would be drained. But after 2001, there was a blip of interest as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) produced a report documenting the drying of the marshes. UNEP stated in the report that the drying of the marshes constituted “the worst engineered environmental disaster of the last century.”

My father, who was one of the first hydraulic engineers hired at the Ministry of Water Resources, had intimate knowledge of the marshes and southern Iraq, and in fact he was the reason why I knew and experienced the marshes, as he took me with him on his rounds (hunting ducks in the process) when I was a young kid. My father gave me information and was able to get me some records as to flow quantities and how one would go about bringing water back to the marshes. So we developed a plan of how the water flow could be restored, and I began advocating with real data that the restoration is possible, and that all that is required to affect restoration was the political will to do so. I was advocating that if Iraq was going to be exempted from the Chapter 7 resolutions, the economic sanctions that the United Nations placed on Iraq for its 1990 invasion of Kuwait, one of the conditions should be the restoration and protection of the marshes.

How did you convince locals, officials, and funders that your project was an important one and that you were the right person/organization to help see it through?

After September 11, 2001, there was a remarkable increase of interest in Iraq, but the news did not cover the marshes angle. The Department of State (DOS) called me in for a briefing, and there were skeptics in the meetings telling me that there is not enough water and that the marshes should not be restored in any case as the culture has died, and the soils were too salty, etc. I argued vehemently and convincingly that this was not the case, but I could not prove it alone as I needed experts that I had no access to (or the money to pay). Soon DOS gave me a grant to convene a panel of wetland scientists who could review our claims and report back to the skeptics whether the claims were substantiated or not.

The panel met in Irvine, California, under the auspices of the American Academy of Sciences, and it was composed of highly-respected scientists who were involved in the Florida Everglades as well as the Mississippi Delta, and the panel concluded its report with “the restoration of the marshes is not only feasible, but warranted.”

The report was published in March ‘03, when Iraq was invaded to remove Saddam. The sudden introduction of a new item to cover engulfed us with news coverage, which brought later interest from the Italian government which was involved in Nassriya. I was asked to come to Rome to brief officials, and the rest is history.

As I stated above, there were skeptics claiming that the Marsh Arabs did not want to return to the marshes. I was pleasantly surprised when I went to Iraq to find out that the restoration had already been started by the locals who breached dikes and stopped regulators and drainage pumps. I began using my knowledge as an engineer to “advise” them as to where to make new breaks and paid for hiring excavators to help in the breaching of large dikes. A the same time, I was making the rounds in Baghdad and internationally raising awareness about the marshes. Italy, Canada, and US were engaged with us from the first days (middle of ‘03), and given the continued success, the funding continued. My challenge was to come up with ideas that would help in making it possible for people to come back and for nature to be restored. The strength that we have is that we always come up with ideas and new ways to interest agencies in the importance of the marshes and designing projects fit for specific requirements of funders.

What are some of the bigger engineering challenges you’ve had to address while helping the marsh residents restore the land?

That question requires pages to answer. I will simplify by saying that the most difficult project/idea that we came up with is how to divert water from the Tigris and Euphrates to restore as much of the marshes as possible in an era of climate change and increasingly limited sources of fresh water. The answers are presented in our Master Plan for Water Resources Management in Souther Iraq (http://www.newedengroup.org/), in which we determined that we can restore 75% of the marshes with as little as 12 billion cubic meters (as opposed to the historic 50 billion cubic meters when the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates were not regulated.

How has the work on the flow regulators been progressing since the recent elections?

The last of the regulators should be finished in April of next year.

The plan for a national park sounds ambitious in a land that needs to be restored, supports local human populations, and faces security challenges. How has this idea been embraced by the government and the local people now that the election is over?

Some of the most ardent supporters of Nature Iraq are the minister and top echelons of the Ministry of Environment of Iraq. We work very closely with them and we are allies, which is strange in the Western experience as NGOs typically have an adversarial relation with government.

Aside from the huge task of marsh restoration, what are some of Nature Iraq’s other environmental goals?

We are now working on creating a series of protected areas all over Iraq and working with the Kurdistan Regional Government as well as local government on the idea of Eco Tourism.

We are also working on reviewing the environmental laws of Iraq and advising on how to modify/amend to comply with international treaties and international standards (or modify to fit Iraqi conditions).