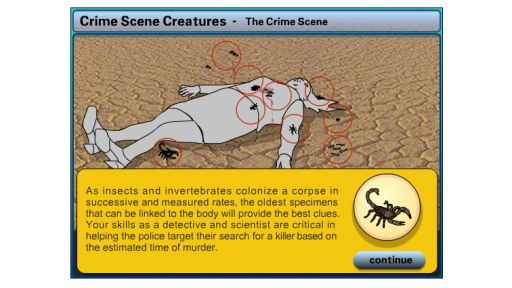

In NATURE’s Crime Scene Creatures, we meet a specialized breed of scientists called forensic entomologists who study the insects associated with a human corpse. Though their work may seem less than glamorous to some, they are in fact vital members of criminal investigative teams.

NATURE caught up with Dr. Lee Goff in his office at Chaminade University in Honolulu, Hawaii and asked him to share a little about the fascinating world of forensic entomology.

Please tell us a little about your role in forensic entomology.

Please tell us a little about your role in forensic entomology.

Forensic entomology is actually any interaction between the insects and the legal system. This may involve stored product contamination, nuisance problems, structural damage (termites, etc.), and medico-legal. I work within the medico-legal or medico-criminal arena. In these cases, about 98 percent of the work involves providing an estimate of the minimum period of time since death through analyses of insect activity on a body.

Q: What led you to choose the field as a career?

My original training was in marine biology. I shifted to entomology more or less by accident. Due to a misprint in the local newspaper, I applied for the wrong job! I thought I was applying for a technician position in marine biology at the Bishop Museum, but was actually applying for a position in entomology. Since I was putting myself through college at the time, I went for the paying position.

My shift to forensic entomology took place over 25 years ago. I was attending the meetings of the Entomological Society of America in San Diego. I had come to the meetings for an early paper and, when I arrived, discovered the paper had been canceled. Not wanting to walk back to the hotel, I went into the session in the next room, where Dr. Lamar Meek (a pioneer in forensic entomology) was giving a paper on one of his cases. I became interested and started exploring the possibilities in Hawaii. It took a while. The combination of basic science with practical applications was what originally attracted me to the field — plus the fact that I’ve always been a little strange. That combination still remains.

Q: At what point are you usually called onto a case?

In Hawaii, I am typically called to the scene as soon as it is discovered and determined that entomological evidence is involved. I go to the scene and begin my examination and collections there. Typically, I also go to the morgue to make additional collections and observations during the autopsy procedure. If the case is on the mainland, I am often contacted while the scene is being assessed and talk the investigators through the process.

Q: How important is it that you collect your data before a body has been moved?

If the body is moved before collections are made, you can lose significant evidence. The insects will leave the body or move to a different part of the body.

Q: Could you describe the materials and methods you apply to your work in the field?

I have a basic kit that I’ve assembled over the years that is small enough to stay on my motorcycle. This includes all of my basic collecting equipment, a net and containers to transport the specimens. My work in the field consists of examination of the body and the surrounding area for insect evidence. Generally, I begin with the upper exposed surfaces of the body and then, as the body is moved, I look at the lower surfaces and then the substrate. I do not remove or otherwise disturb clothing during these examinations so that other types of evidence will not be disturbed. For the immature species, I split my collections into two lots. One lot is fixed and preserved at the scene in order to stop the biological clock. The other is placed into a rearing container to allow me to rear these specimens to the adult stage in the laboratory for a positive species-level identification. Many times the adults are easy to identify but the larvae are indistinguishable. Collections are made from all different areas of the body and surroundings, and these are all kept separate. I also make collections during the autopsy procedure. In the morgue, I can spend more time going through clothing for species I may have missed in the field. Examinations of the internal tissues and wounds may also yield species of major significance to the final analyses.

Q: Could you describe how you work with other forensic scientists to piece together a case?

I provide only one piece of the puzzle that is the crime. Others work to provide other pieces. We typically work independently, each on their own area of expertise. Generally speaking, I do not solve cases. I only provide analyses of the evidence. I leave the solutions to law enforcement. Forensic workers who decide they will solve the case based only on their piece of evidence frequently become part of the problem and not the solution.

Q: Approximately how many cases have you taken on?

The number of cases per year varies, depending on the homicide rate and what is done with the body. Generally, I work between 10 and 20 cases per year. Hawaii has a very low incidence of violent crime, so my cases are fewer than if I was based on the mainland. To date, I have presented opinions on over 300 cases and consulted on more.

Q: In general, how do you judge the success rate of your work?

A success rate is a matter of opinion. I do not judge by convictions but rather by completion of my analyses. I work to provide an unbiased, objective, scientific analysis of the evidence. When I’ve been able to do this, I have been successful.

Q: Where do you see the field heading?

The field is expanding into areas we had not thought possible only a few years ago. Our research is becoming more detailed, and advances in technology are necessitating a reexamination of many previous studies. Advances in computer technology and DNA research are opening areas not previously considered. We still must remember to stay within the limits of our sciences… Secondly, the flies alter foraging behavior. When a female phorid detects a fire ant worker, she’ll stalk her victim, making the worker run and hide to evade attack. As the ants spend more time avoiding the flies and less time foraging, the entire colony is negatively affected.

Q: Do you find that the popularity of forensic TV programs is generating more interest in the field? Do you feel they do a fair job of depicting the work of forensic scientists?

The recent explosion of forensic shows has definitely increased awareness of the general public and, more significantly, students of the various disciplines in the forensic sciences. Here at Chaminade University, I have observed a phenomenal increase in the students majoring in forensic sciences. I began here approximately six years ago with 15 forensic sciences majors in our bachelor of science degree program. I now have 95 declared majors and another 65 who have indicated they will be declaring forensic sciences as their major. Significantly, these are students of very high caliber who may have earlier been looking at medicine or biology.

The high profile of the TV shows has also increased the expectations of juries. They now expect some type of forensic evidence and almost appear disappointed if they don’t get any. Some people regard this as a problem, but I view it as a positive in many respects. When I began, the jury tended to behave as deer caught in headlights when confronted with scientific evidence. Now they are prepared to hear this type of evidence. If the individuals involved in preparing the cases have done their work properly, they should be able to present this information in a palatable form. In like manner, they should be able to explain the absence of such evidence. As for the reality of the shows, we must remember that they are typically one hour in length and designed to be entertainment, not reality. This includes the “reality shows.” I have worked with the CSI Las Vegas show since the first year. With this group, I have found that they are quite concerned with keeping things within the realm of reality. The time frame is off, but the show is only an hour in length, including commercials. When I have made suggestions concerning my own discipline, they have been more than willing to make appropriate changes.

Q: Are there any general misconceptions about the field?

The most common misconception with regard to forensic entomology is the level of precision of our results. We provide estimates of a period of insect activity on the body and not the actual period of time since death. These are often quite similar, but not always. We begin with ranges in hours, then days, months, season, and, finally, “It’s been there a long time.” This is the reality. If an entomologist states that the “death took place at 3:45 p.m. on the 10th of June, 2006,” you might want to consider that you actually have a potential suspect! The entomology cannot give you those types of results. On the other hand, it can be close enough to establish or destroy an alibi.

Q: Does it take a certain kind of person to handle this kind of work?

It does require a certain type of individual to deal with this work. I guess the bottom line is that you do need to be a little weird to go into this field. At least, that’s what I tell my students. I also tell them that being a little weird is actually a good thing. The successful individuals will develop a somewhat strange sense of humor. This is a defense mechanism that works quite well, even though to those outside, it may seem callous. Underneath this, there is still a sense of compassion.

Many people think it is great when watching from a distance, but find that the reality is not for them. We do willingly go to situations and deal with things that most people tend to avoid. You need an ability to detach yourself from what you are working on at the time. If you allow yourself to become involved in what happened to the individual or what their last moments of life were like, very rapidly you lose your objectivity. Once this happens, you consciously or unconsciously begin to become an advocate for the victim. If your work is to be meaningful, you can only advocate for the truth regardless of where it leads.

To a certain extent, I’ve found a way to remain a small child. When we are small, we are encouraged to wonder about things and turning over rocks to see what’s underneath. Then we reach a point where society tells us to “grow up” and stop turning over rocks. By working in science, I’ve found a way to continue turning over rocks and wondering what is underneath. Of course, I really don’t turn over many actual rocks these days. I turn over other things, but the idea is about the same — although I’m a little more detailed in my actions. There is a benefit to society in what I do.

Q: Do you ever have nightmares?

I do have nightmares on occasion, but not dealing with my work. These generally involve my in-laws moving in permanently or my children deciding to come back home. I used to have one in which I became an administrator. My worst is where I sell my Harley and buy a car. Fortunately, these are all quite rare!

Q: What do you enjoy most about your job?

I enjoy the challenge and unpredictability. These go with forensics in general. No two crimes are alike, and you have a constant change in data and approach. No two days are alike. I can become so lost in the complexities of the interactions between insect species and the body and each other that I can almost forget what I am actually working on. I also like the idea that I am, in some small way, making for a somewhat safer world.