Fraser’s. Hector’s. Spinner. Rough-toothed. Bottlenose.

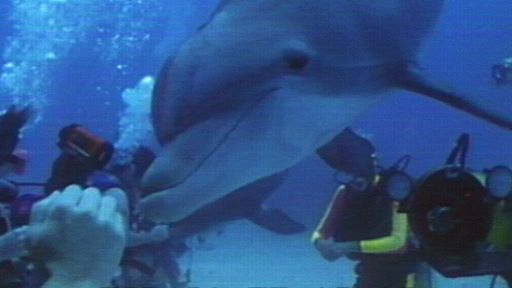

They are just a few of the nearly three dozen species of dolphin that glide through the earth’s oceans, at home in a watery world most air-breathing mammals would find hostile. But as NATURE’s Dolphins: Close Encounters shows, these small whales have proved remarkably rugged and intelligent. Indeed, people have come to admire these savvy athletes of the sea so much that dolphins have become the object of a billion-dollar entertainment industry. Each year, millions of fans pay to watch — and even swim with — their favorite animal. But the dolphin’s popularity also raises a troubling question: are these captive performers our willing partners — or our prisoners?

Like their close relatives the porpoises, dolphins are small whales that have teeth instead of comb-like baleen. But while porpoises have spade- or shovel-shaped teeth, dolphin teeth are sharp and pointy, perfect for grabbing a fish, crustacean, or squid. Like bats, many dolphins are apparently able to locate and home in on their prey using a kind of sonar, producing clicks and pulses of sound that bounce off the target. Some can dive to extraordinary depths, nearly one thousand feet below the surface, to find food.

The dolphin’s sonar and swimming prowess, however, aren’t the only traits that have made the animal so interesting to people. Dolphins also have social skills that have endeared them to mariners and fascinated scientists. Sea lore, for instance, is full of tales of dolphins that rescued drowning sailors by holding them up near the surface and pushing them to shore. Such stories, researchers note, may arise from the fact that dolphins do cooperate to help lift ailing relatives and newborns near the surface to breathe. And some dolphins do push floating objects around the ocean, for reasons researchers don’t fully understand.

In many ways, in fact, dolphins behave like people. They are highly social animals that often live in groups and take great pains in caring for their young. Dolphin mothers often babysit their calves for up to two years, until they are able to survive on their own.

But gaining insight into the lives of wild dolphins, which often live hundreds or thousands of miles from shore, has been difficult. There are places, however, where the conditions are just right for studying wild dolphins. One is Australia’s Monkey Mia beach. Here, as Close Encounters shows, clear waters and remarkably tame dolphins have allowed researchers to get close to their subjects.

For more than 30 years, the wild bottlenose dolphins have been visiting the remote beach on Shark Bay about 400 miles north of Perth. Most mornings, small groups of dolphins — which are well-known to residents by markings on their dorsal fins — swim in to snack on fish offered by visitors.

While the feeding is carefully regulated to prevent the dolphins from becoming overdependent on the human handouts, the practice has helped draw hundreds of animals to the Bay that aren’t frightened by people. As a result, Monkey Mia has become one of the most active dolphin research centers in the world. Since the 1980s, dozens of researchers have traveled to the area to study everything from mother-calf relationships to dolphin dating.

These studies have added much to our understanding of dolphins. Some researchers, for instance, showed that dolphins can use tools — a skill that at one time only humans were believed to possess. At Monkey Mia, the tool is a sea sponge, which the dolphins carry in their beaks, apparently to help stir up food from sea grass beds. Other scientists have tried to understand why some dolphins seem extremely attracted to pregnant women that visit the beach.

Still other studies, such as one by biologist Rachel Smolker, who is featured on Close Encounters, have examined dolphin speech patterns. Smolker and colleague John Pepper found that young male dolphins on the prowl for mates form alliances that appear to be cemented by sound. At first, the two males will have very different patterns of squeaks and clicks. Over time, however, the duo will develop a single, unique signal, perhaps to help them let each other know when an attractive potential date appears.

At Monkey Mia and other dolphin havens, however, development and pollution threaten to disrupt the lives of dolphins. But researchers hope that their work will help fuel conservation efforts. “The more we know about dolphins’ social lives and their specific environments,” says Diana Reiss, a Rutgers University researcher, “the better equipped we will be to protect and preserve their diminishing coastal habitats.