Lynne Richardson and her husband, Philip Richardson, directed and produced Drakensberg: Barrier of Spears. NATURE spoke with them in January 2009 about the making of the film.

Q: You produced Murder in the Troop, which was broadcast on NATURE in 2006. What are some other film projects you’ve worked on since then?

A: One of our more recent films was Walking with Lions which was about us following a pride of lions whose territory was focused around a spring along the escarpment of the Zambezi valley. Here the terrain was so rugged that we were forced to follow the lions on foot.

Our last film was about Namaqualand, about how in spring the desert along the southwest coast of Africa transforms to produce the most spectacular flower show on earth. But the spring is short-lived and soon the rains dry up and temperatures soar to over 115 degrees F. As the land dries out and the plants wither and produce seeds we look at the adaptations of the various birds, mammals, insects and reptiles to surviving in this boom or bust environment.

How did you become interested in the Drakensberg as a potential subject for a film?

The Drakensberg is possibly the single most dominant geographical feature of southern Africa and so it is a must do film if one lives here. Furthermore it is a most unusual mountain range, sub-tropical at the bottom, alpine at the top, steep gorges and buttresses on one side, and flat-topped on the other.

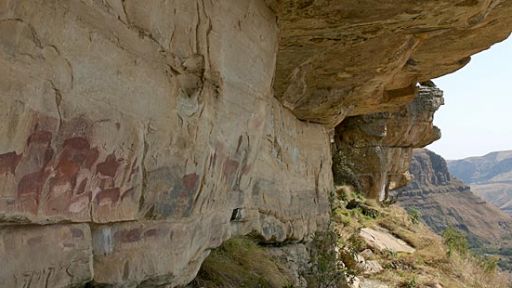

The mountain range is a setting that seems to carry its history with it — from the ruts carved into the rock by ancient migratory paths to the rock art on cliff walls. What impression did these markings from the past leave on you?

When you climb this mountain you very quickly realize how small you are — both in time and space. Everything here is so huge and ancient. The animals and the people have been living here for millennia, so although one feels totally insignificant here, you also feel hugely privileged to be able to glance back in time and see the markings of history before your eyes.

Did the focus of the film change as the project evolved?

We spent a lot of time researching the film, so by the time we began shooting we had a pretty good idea of what we wanted to film. Nevertheless, when you really start to live and feel the mountain, one’s perspective changes from being largely academic to being much more intimate.

How long and how often did you spend time in the field? What were conditions like?

We spent periods varying from about a month to a minimum of a week in the field. We had a base camp at Giant’s Castle Nature Reserve, and here we were very fortunate to have the permanent use of a small thatch “bunk house” built next to some unused stables. So here we were pretty comfortable and had electricity and mobile phone reception for emails, etc. However, whenever we left camp for periods of a day or more, we could very quickly become vulnerable to the sudden changes of the weather. The Drakensberg is renowned for its very changeable weather and it can snow any month of the year. In summer one gets very heavy mists, it often rains for days on end, and in winter it can obviously get very cold. So when you go out you have to be prepared for anything.

We went on a hiking trip about once every six weeks and this would last from about three to six days. On the long trips, like when we camped above the Tugela Falls, or below the bearded vulture ossery, a field assistant went down once or twice to fetch extra provisions.

Could you tell us about some of the equipment you carried with you?

When operating out of Giant’s Castle on a daily basis, we were normally a team of two or three persons, carrying the camera with lens, the tripod and fluid head, and backpacks with long lenses, a matte box, filters, spare tapes, batteries, food, water, some warm clothes and sometimes extra sound recording gear as well.

On our camping trips we needed a team of at least four people. Now we carried all of the above plus obviously a minimum amount of camping equipment but still sufficient to withstand freezing cold and very high winds. This very quickly added up and we generally found ourselves carrying over 20 kg (about 44 lbs) per person. On a trip to the top of the escarpment this would amount to a walk of about 7 to 10 km (about 4 to 6.2 mi) and a climb from about 1,500 m to 3,200 m (about 4,900 ft to 10,500 ft). So on these trips conditions were pretty tough but always worth it.

How did you travel in such diverse terrain?

There are very few roads in these mountains, so virtually all the filming was done on foot. One can travel to the main camps and reserves by vehicle, but once you get there you are on foot.

What was it like to work among the eland? How did you get close enough to capture some of the intimate scenes in the film?

The small groups of eland near camp were quite tolerant of people and if you approached slowly, or let them come towards you, you could get quite close. But the large herds on the slopes below the escarpment were very frustrating. Very often they would start running off when you were still over a kilometer (about 0.6 mi) away. The only way we could get close to them was either in the mist when they could not see us (or vice versa) or by putting up our small portable hide along a route they were taking and to hope they would come past.

Was anyone bitten while filming the shots of the ou-hout bushes and the miniature ecosystem that thrives among the branches?

We got stung occasionally by the ants, but it was not that bad and is all part of the game. The whole idea was to film them undisturbed, so like most animals in the bush if you leave them alone they will leave you alone.

The fire scene is a very striking moment in the film. What was it like to be there when the fire broke out?

Dramatic and a little scary. Veld fires are always dangerous, but we made sure we had an escape route before getting close to the fire. Once the fire had burned for a while we stayed in the burned grass. The wind swung around a lot so quite often we got a face full of hot smoke, but at least we knew that we could not be burned. When the fire started we were close to hard rocky soil with sparse, short grass so we stayed there until we had a safe burned area we could move onto.

We were actually more concerned for the animals, particularly the eland, but they are such mobile and surprisingly agile animals that it would take quite some fire to corner them.

Are there any other exciting or interesting off-screen moments that you can share with our readers?

It is probably the structure and beauty of the Drakensberg that provides its most memorable moments. Sitting on a mountain that is almost flat on top and then looking over the edge down a sheer 600-meter (nearly 2,000-foot) drop is a pretty awesome experience. And then to fly over this area with its solid rock cathedral-like spires shooting up towards you is something you will never forget.

Another exciting moment was when we were filming ice rats in the mist one afternoon. Suddenly it started snowing, then dark clouds rolled in and then lightning struck so close to us that we could actually smell it. We headed for home pretty smartly after that.

Photos © AWF