TRANSCRIPT

[airy music] [epic airy music] - [Murray] A baby eland is no sooner born than it must face a violent opponent.

[thunder booming] Torrential rains sour the herds food.

The slopes become a green desert, grass everywhere, yet not a blade to eat.

Hungry, the eland begin an epic climb [bird screeches] to the peaks of south Africa's largest mountains, the Drakensberg.

[dramatic music] But the weather bites anxiously at their heels.

[fire raging] The mountains are both their home and their obstacle, and the quest they must conquer each year to survive.

[dramatic uplifting music] [group vocalizing] This is the Dragon's Mountain, the Drakensberg, the heart of the highest, widest, and most rugged mountain range in all of Southern Africa.

There are many stories to be told about these mountains.

The smoke of grass fires recalls their fiery birth.

While eyes in the sky scan the barren slopes for signs of death, it is the story of new life here that is so remarkable.

[dramatic uplifting music] While some of the Drakensberg's characters feast, others prepare for famine and vicious weather.

But it's the journey of the eland, the world's largest antelope, from the foot of the mountains to their very peaks that brings to life the scale, the beauty, and the drama of the Drakensberg.

The dark power in this story comes from the mountains themselves.

They loom over everything with cliffs that seem like the spines of a dragon.

These mountains are far, far older than the creatures they dominate.

They were born some 160 million years ago.

[lava splashes] In the Jurassic period molten lava poured out across the region and cooled into layers of basalt.

The toughest segments of the basalt now cap the Drakensberg's peaks.

[dramatic airy music] Any softer rock has been eroded away over tens of millions of years to leave the valleys and ravines of today.

The Drakensberg mountain range stretches more than 600 miles across Southern Africa.

Relentless erosion has sculpted shapes that inspired the Zulu name, Barrier of Spears.

[group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] From the peaks the slopes plummet some 6,500 feet into the lower valleys.

And vultures fly so high that local legend says they can see into the future.

In the dry season, it is hard to imagine that the Drakensberg is a source of many rivers flowing west into the Atlantic and east into the Indian ocean, irrigating a vast area of farmland and pasture.

[bright music] Down in these fertile valleys eland are gathering.

[eland grunting] The grasslands of the Drakensberg remain a precious refuge for these wild herds.

The mighty basalt bastions are literally built on sand.

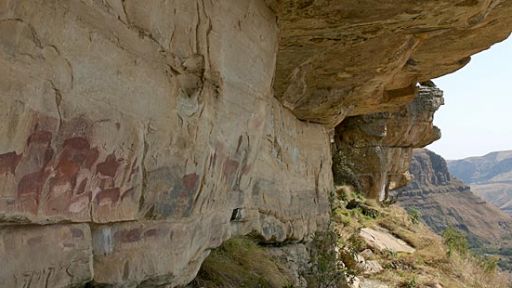

The smooth protected sandstone cliffs at the base of the mountain are an open air gallery of primeval rock art, some 2,400 years old.

[group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] The hunter-gatherer clans who painted these images have long disappeared, but the eland are remarkable survivors.

They are almost as big as oxen.

Bulls stand nearly six feet tall and weigh in at more than 1,500 pounds.

They're too big to be climbers like ibex or chamois.

Now in early summer, the eland graze contentedly in the gentle grasslands of the lower valleys.

The youngest member of the herd is not even five minutes old.

Each mother knows her own calf and attends to no other.

The young eland takes in this bright new world with big eyes and ears, while it's nostrils are becoming familiar with the scent of its herd.

Throughout its life this scent will feel like home.

Just a few hours into its life, the calf knows hunger.

And for the next several months, its survival will totally depend on its mother.

[flies buzzing] Eland are born throughout the year, most of them in the early summer.

While the calves are small, 10 to 15 mothers will form a nursing group that won't move on as rapidly as a big herd.

In such a small slowly moving group, the little calves get enough time to rest.

While their mothers are busy grazing and producing milk, the calves lie low in the high grass and are busy too, growing.

Higher up the slopes, midway between the valleys and the peaks, is the home range of clan of climbers.

[group sings in foreign language] [monkeys grunting] [cheerful music] - [Murray] Born small but smart, chacma baboons rely on their intelligence for survival.

The baboons that are born here never roam far from the cliffs that offer protection.

Like the eland, they are usually associated with Africa's savannas.

But a few groups have found that the high terrain has its advantages, especially when bringing up babies.

[animals grunt] A black-backed jackal would pose much more danger down in the bushland of the plains.

Up here, the steep open terrain works for the baboons.

On these rocky slopes the jackal can't keep up.

Yet the male baboons grab the opportunity to show off their power and draw a line that's not to be crossed.

The jackal gets the message.

As soon as the excitement is over, the little ones are allowed to dismount from their mothers' backs and rejoin their friends.

[playful music] [baby baboons squeaking] Eland mothers will fiercely defend their calves, as long as they notice the approach of an enemy.

The calf has caught the jackal's scent and seems to sense the danger, but he's too young to run fast.

The jackal knows the mother is close, so he is careful.

In fact, she is already closer than he hoped.

Once again, the jackal is out of luck.

[dramatic bright music] In summer, heavy winds prevail in the Drakensberg mountains.

These winds bring masses of moisture from the ocean a hundred miles away.

For the residents this can mean a cold wet snap at the very outset of the warm season.

The changeable weather is another reason why the baboons appreciate their cliffs.

Even when the rain pours down for an entire week, they have a roof over their heads.

[gentle music] [rain tapping] There's no such luck for the eland.

They must rely on their smooth water repellent coats and their huge bodies for protection.

But small calves are vulnerable to exposure.

The mothers have to keep them moving.

When the skies clear, the herds will soon recover and be rewarded for their endurance by fresh green grass.

But this summer, one cold front chases another, soaking the landscape and its inhabitants.

Eland are desert dwellers by design and specialize in enduring hot dry periods.

This cold wet weather pushes them to the limit.

What's worse, the old dry grass is beginning to rot in this permanently wet condition and quickly loses its nutritional value.

At a time when the need extra nourishment, their pasture is turning into a green desert.

Hunger and cold make them feed more than ever, yet their daily intake is rapidly becoming worthless.

The suckling calves make enormous demands on their mothers.

and for the smaller ones the constant rain brings the danger of hypothermia.

[group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] At this season and in this weather, the nursing herd hardly ever stops.

Eland are nomads and their range is enormous.

It's time for the mothers to take their calves to higher ground where the mountain pastures are just beginning to green.

There's only one thing that can draw a crowd like this from the sky.

The strain of the past few weeks has been too much for one of the younger calves.

But the jackal's day may have finally arrived.

[vultures screeching] [jackal grunts] After the cape vultures have crowded in, the bearded vulture makes an entrance.

It's a bone specialist, not really part of the competition for meat.

[vultures screeching] Bearded vultures have a wingspan of nearly 10 feet.

This one is carrying a load of five or six pounds in its talons.

But its beak is not strong enough to crack bone.

Getting to the marrow calls for a special solution.

[bone thuds] Bearded vultures drop bones deliberately to shatter them into pieces.

[vultures screeching] They can completely digest bones, which will be dissolved by extra strong acids in the vultures' stomachs.

Marrow makes up 90% of their diet.

Next morning, all that will be left of these bones will be a bright white splash below the vultures roost.

[vulture screeching] [group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] These big birds are master gliders.

with hardly a wing beat, they surf the thermal upwinds along the Drakensberg's sun-baked cliffs.

These dark faced juveniles are still experimenting with their new flying skills.

[person sings in foreign language] - [Murray] From these cliffs pours the world's second highest waterfall, the Tugela Falls.

The falls drop more than 3,000 feet to the point where the water becomes veil of rainbows.

[waters rushing] In spite of the fact that the Drakensberg is Southern Africa's main watershed, some of these waterfalls are only here for part of the year, during the rainy season that is now bringing the vast grassy plateaus into green.

[bright music] After a steady climb, the eland have reached the lofty midsummer pastures halfway up the Drakensberg.

Here the grass is getting greener by the day.

Range of wild flowers on these slopes reflects the mountains' harsh climate.

Most of them are perennials.

The same deeply rooted plants will blossom year after year.

Plants that die each year and depend on seeds to germinate in the next have little chance up here, because in a bad year, unreliable weather will frustrate germination and flowering.

But this year, a sweet fragrance in the summer breeze mobilizes an army of tiny monsters, a beetle from the Scarab family senses that the special flower it lives for is ready for a visit.

This is the Drakensberg's most distinctive flower, the protea.

It attracts protea beetles like other flowers attract bees.

The beetles come to feast on its nectar.

And as with bees, the hairs on their bodies brush pollen from the flower, for seeding the next protea they land on.

Insects are not the only pollinators.

With its long bill, the sugarbird dips deeply into the flower to satisfy its appetite.

And, like the beetle, receives a dusting of pollen on the feathers of its head.

Where shallow soil offers few nutrients, a plant depends on a sinister trick to flourish.

To a fly, the sundew looks irresistible.

But instead of enjoying a feast, the fly will soon be a feast itself.

It's trapped by the sundew's sticky pads and will be digested by the plant's enzymes.

The gentle mountain breeze carries other scents as well.

And the big eland bulls find them most exciting.

[eland grunts] The females are ready to mate again and they signal their readiness with pheromones.

They may be ready, but not for just anyone.

Venting his frustrations in the grass has left this suitor with a hat.

[group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] Unlike the roaming eland, the chacma baboons never venture far from their rocky terrain.

Watching their mothers gather food, the youngsters learn what plants are edible and where to find them.

Not all meadows are the same.

Vast green areas are now covered with grass that's hardly edible for baboons or eland.

What was left of their nutritional value after they produced seeds has been washed out by the rain.

The quality of the grazing changes with the weather.

And there are few places in Africa where the weather is as changeable as in the Drakensberg range.

Too much or too little rain can both mean hunger for the herds.

[emotional music] At the height of summer, rain and thunderstorms move in almost every noon.

The baboons are stoic about it.

Now that the rain and the wind are warm and not unpleasant, they simply go about their daily routine, and having a shower is part of it.

[baboons grunting] [group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] Within weeks, the green flanks of the Drakensberg will turn to autumn brown.

The eland now turn from grazing to browsing, but bushland and trees are scarce on the roof of South Africa.

The pressure big plant-eaters exert on any vegetation is obvious.

Yet over time, the shrubs have found a way of pitting one enemy against another.

Ants that inhabit these ou-hout bushes have a fiery bite.

By defending their habitat they spoil the browsers' appetite.

The ants are here to care for their livestock, huge aphids that suck the sap from the bush and in turn produce a sugary secretion, which is consumed by the ants.

[gentle music] again and again, an ant will eagerly receive the sweet and nourishing droplet released by the aphid.

Tenderly the ants care for a vulnerable member of their herd, an aphid that has just malted its shell.

In the balance, both the aphids and the ou-hout bushes seem to profit from the ants' presence.

The young leaves may be tasty and nutritious, but every mouthful is bitterly seasoned with the ants' chemical weapon.

The eland have to move on, but all too often, some of them fall by the wayside.

[crows cawing] It's another calf, and the crows have found it first.

Some 70% of eland calves may die within their first year.

Getting enough food is the first key to survival.

The mothers have clearly lost weight.

Fresh, tender grazing is sparse and the calves keep coming back for milk.

[somber music] [vulture screeching] The herd is under constant surveillance.

Scavengers are watching them waiting for the weak.

[vultures hissing] The thriving vulture population of the Drakensberg is a good indication of the high mortality rate among big animals here.

[vultures hissing] Competition over the carcass is fierce.

Once more, the jackal has to give up in frustration.

[somber music] The plateaus and slopes are dry at this time of year, but there is still a constant flow of water down in these canyons.

Drawn by the green vegetation along the river banks, the eland have followed a river upstream.

But the strip of green along the river is narrow, and pickings are not great.

Soon the herd will have to move on again, and track in earnest up the mountain.

By now, calves have to feed themselves.

Their digestive systems have switched from milk to grass.

They have become ruminants.

The eland bull is hardly aware of the strange world below the reflecting surface of this little mountain river.

The wide-mouthed river frog is a ferocious predator, the top predator of this watery realm.

A river crab.

There are not many places in the world where frogs hunt crabs.

Digesting this bite will take a good while.

The crab has been swallowed whole.

It's still alive in kicking.

[waters rushing] The eland set out on the last and hardest leg of their epic track.

[hopeful music] For the calves, every step of this journey is new.

The older animals have been through this annual cycle before.

They know that the grass is truly greener on the far side of the hill.

[group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] A steep slope is not a safe place to stop and rest, so they keep going until they reach level ground.

As they climb past the mid-level plateaus, they leave the baboons behind.

[bright hopeful music] The highest peaks of the Drakensberg reach up more than 10,000 feet.

Most of the pastures up here are well above 6,000.

As soon as they arrive, the animals reap the rewards of a long, hard climb.

The grass is sweet, nourishing and delicious.

But these high alpine meadows are a danger zone.

The weather can lash out in an instant.

[thunder booming] The baboons seem to know what's coming.

[bolt strikes] They've seen many thunderstorms, yet each new one seems to terrify them.

Lightning may strike anywhere, and the fire can race across the land faster than any animal can run.

[fire raging] [dramatic emotional music] Rain would usually accompany a lightning strike and help quench the fire.

But the atmosphere above this part of the Dragon Mountain is dry.

So dry, that rain raindrops evaporate long before they reach the ground.

The fire sweeps on mile by mile.

Soon the entire mountain is shrouded in smoke.

Even when the animals can escape the flames, there is a danger of suffocating.

Within hours, the mountain paradise has turned into a fiery hell Drakensberg, the Dragon Mountain, earns its name.

In the long run, such grass fires are a blessing for the eland, because they clear the ground for fresh new growth and good grazing.

But for now, the pasture is gone.

[soft somber music] The fire has spent itself.

The smell of charred vegetation will fill the air for weeks to come.

The bearded vulture glides over scorch slopes and smoke-filled canyons knowing there will be a rich aftermath.

[solemn music] The eland have escaped the fire, but now the Drakensberg seems set to starve them out.

Instead of fresh pasture, all they can smell is cold smoke.

Anything that survived the fire is now underground.

This is difficult terrain at the best of times.

Finding another place where the grass is still green will mean a long and hungry hall.

The fire has reached down the slope into baboon country.

The eland are natural nomads, but the baboons stay put and make do.

Their intelligence makes the baboons versatile.

They realize that there are tubers to harvest beneath the scorched surface, and they will spend the next few weeks digging.

[baboon grunts] When misfortune strikes, the comfort of strong family ties means everything.

[crow caws] The baboon's social network seems to be a key resource in coping with the harshness of their environment.

From the early days of life, it's these tender and lasting personal bonds that support each individual in this struggle to survive.

Higher up where there is moisture the grass on the blackened slopes responds quickly and turns green.

The new grass is fertilized by the ash of the old, but there's not much and not enough for these herds of massive grazers.

[somber music] The herd has no choice.

It has to move on again.

Cold fog creeps up the slopes, following in the footsteps of the fire.

The temperature drops close to zero, and cold can kill the young.

[dramatic music] A vulture may have spotted what this male baboon is looking for.

[somber music] And finally finds.

[vulture screeches] Down below the mother knows something is wrong.

Baboons can carry dead infants for days not wanting to let go.

The father takes the little body back to the shelter off the cliffs.

[solemn music] Between the fire and the cold, the parents have lost almost everything.

The rugged basalt cliffs near the top of the Drakensberg bear the scars of generations of migrating eland.

[group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] The ancient paths lead along the cliffs to a plateau.

This late in the year, the top of the Drakensberg is the only place where there is enough edible grass.

The world's largest antelopes have become mountaineers to reach it.

[group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] Yet, one could not say that the eland have arrived.

These nomads never arrive.

Their entire life is a constant flow, and there is no place they will stay for long.

Even the bonds between them don't tie them down.

They drift in and out of herds as they please.

But today a grooming session is taking priority over precious grazing time.

They are being quite as unselfish as they may seem.

They're licking off each other's salty sweat for the minerals it contains.

Grooming also helps discourage parasites, and its greater purpose is to give and receive reassurance.

The autumn-born half is fortunate.

Its mother is still in prime condition and able to provide a rich flow of milk.

Even on this high plateau, the eland are not alone.

Ice racks also forage up here.

They're stockpiling seeds preparing their burrows for winter.

With their thick fur they could be Arctic rodents.

[bright music] And wherever there are lots of rodents, predators are on the prowl.

The super large ears of the serval will catch the slightest rustle in the undergrowth.

Underground, the ice rats are safe from the serval and from the approaching winter.

[group sings in foreign language] - [Murray] before the first winter storms hit, the eland will have to leave.

Each year, the ice rats see them come and go.

No matter who or what passes over this mountain, the ice rats will hold out in their safe bunkers.

If the Drakensberg is a strong hold of any sort, it's definitely theirs.

The eland are under pressure now to build up fat reserves for the cold season.

As the first Antarctic front rolls in from the south, the calves get their first taste of a high mountain winter, a hail storm.

[soft somber music] And then, silently, snow begins to fall.

Snow in Africa is something extraordinary.

The Drakensberg is one of the few places that receive it each year.

The herd may take a day or two of such whether, but they cannot stand the cold for long.

Again, the young and the weak are at risk, and some do remain behind as the herd moves on.

[dramatic majestic music] The worst of the Antarctic front has passed.

The ice rats emerge to appreciate every hour of sunshine.

These hardy little rodents don't hibernate, for although the winter may be harsh, it would only last about two months.

The snow melts away, peeling the last of this year's casualties.

[soft majestic music] The eland herds have moved down and away seeking the lower valleys.

The surviving calves have come safely through famine, fire, and snow.

On their way down to the foothills of the Drakensberg the eland once more pass the ancient record of their everlasting journey.

Their own record, legible only from the air, has been inscribed right into the mountain side of the Drakensberg.

Generation after generation thousands of hooves have left their mark on the delicate ground, winding narrow path to impossible terrain and enduring line across the seasons and down through the years.

This rock of ages stands as a timeless testament to the ancient and the everlasting.

Yet the Drakensberg is also a monument to change.

Cataclysmic at dawn, slow and steady over the eons, but always unpredictable, each and every day.

[epic music] [group sings in foreign language] [dramatic music]