Each spring, the skies above the rugged, volcanic shores of Iceland’s Lake Myvatn echo with the sound of whispering wings. Like ponderous ghostly kites, great white swans dip and glide to splashy landings in the crisp waters.

Wildebeeste migrate in search of food and water. Wildebeeste migrate in search of food and water. A continent away, great silvery fish leap frothy waterfalls. The sockeye salmon are battling their way upstream, back to their ancestral spawning grounds in Alaska. And on the other side of the globe, great herds of broad-shouldered wildebeest tramp across African plains, following age-old trails to food and water.

Spurred by seasonal changes, each of these animals is partaking in one of earth’s greatest, and most mysterious, rites: migration, the subject of NATURE’s Earth Navigators. It takes viewers along for a sometimes breathtaking ride on these remarkable treks, which can be as short as a walk across the street or as long as a 20,000-mile flight from pole to pole.

Four travellers are the stars of Earth Navigators. One is the whooper swan of Britain’s Norfolk Marshes, which takes off each spring on a hazardous 400-mile flight across stormy seas to nesting spots in Iceland. Another is the fragile Monarch butterfly, which can take a year and three generations to complete its 6,000-mile trip from Mexico to Canada and back. Africa’s wildebeest is a bit more robust, but its 2,000-mile circuit includes plenty of hazards, from hungry lions to ferocious crocodiles. Then there are the salmon, which have a sense of smell so acute, they can find the streams where they were born after years at sea.

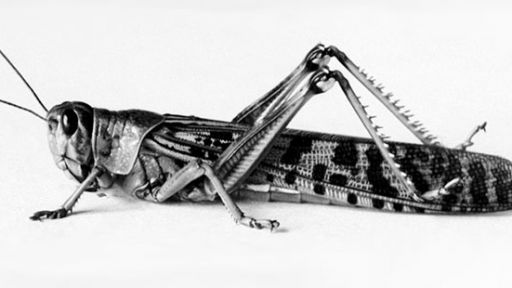

But other travellers also take a turn in the show’s spotlight. They include the amazing Arctic tern, a seabird that each year flies nearly pole to pole in search of warm weather and adequate food. And the grasshopper-like locust earns some memorable scenes, in which it tranforms from a homely hopper into a seething million-strong swarm that can swoop down on a farmer’s field and devour the crops in just hours.

For many animals, the urge to move when the days change length and temperatures vary is programmed into their genes. Somehow, young birds can unerringly fly from summer nesting grounds toward wintering ranges they’ve never seen — and then fly back again the next year. Monarchs butterflies perform an even more amazing feat: the flappers that return to the wintering grounds in Mexico are actually the granchildren of those that left the previous spring. It takes three generations for the insects to complete the trip.

Just how these animals find their way around, however, remains mostly a mystery. Researchers have evidence that some migrating animals use visual landmarks — just the way people do — while others steer by the sun, the stars, or even by following smells and the earth’s invisible magnetic field. But “we don’t really understand how these things are actually done,” says researcher Howard C. Hughes of Dartmouth College in Hanover, NH. Even sophisticated sonars, computers, and satellite positioning systems, he notes, sometimes barely equal the navigational power of a bird’s tiny brain.

Some seabirds use “smell maps” to navigate. In his award-winning SENSORY EXOTICA: A WORLD BEYOND HUMAN EXPERIENCE (MIT Press, 1999), Hughes explores the highly specialized senses that may help some animals along their journeys. German researchers, he notes, have collected evidence that some songbirds carry biological compasses that detect magnetic fields. Each spring and fall, the scientists found, the caged birds they were studying became agitated, hopping and flapping about their cages. Careful observations showed that in fall, the birds typically tried to move south, while they seemed to feel the urge to fly north in spring. Somehow, the birds were able to maintain a sense of direction even when shut inside a room, away from clues provided by the sun, stars, or weather patterns.

When the researchers installed shielding that blocked the earth’s magnetic field, however, the birds appeared to lose their sense of direction. And, more tellingly, says Hughes, when the researchers used powerful magnets to alter the magnetic roadmap, the birds could be fooled into trying to fly in the wrong direction. Such exotic senses, Hughes says, may allow the birds “to navigate with astonishing accuracy.”

Similarly, the salmon and some seabirds use “smell maps” to navigate. Biologist Gabrielle Nevitt of the University of California, Davis, has suggested that such odor paths may be particularly useful to animals that must find their way over relatively featureless landscapes, such as huge tracts of ocean. Together with other scientists, Nevitt has shown that high seas birds known as petrels can home in on a gas emitted by tiny plants that grow in the sea’s surface layers. The birds are “navigating through an olfactory landscape,” she says. But it is unclear if the birds use the smells, which can be useful in finding food, during migrations.

Why haven’t people evolved similarly powerful navigation systems? “We’re not really a migratory species,” says Hughes. “We might be nomadic, but we don’t make these long trips on a seasonsal basis. So there was no [reason to evolve] a long range navigation system that would help us pinpoint our location on the globe.”