In the world of migrants, the petite Arctic tern is a champion. Each year, the robin-sized seabird, featured in NATURE’s EARTH NAVIGATORS, travels up to 20,000 miles from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back. The feat is even more remarkable, researchers say, because the bird almost never rests. It is constantly either in the air, diving for fish, or bringing food to its nestlings.

Why such a long journey? It’s probably a by-product of the earth’s geologic evolution. Millions of years ago, when the continents hadn’t yet drifted into their present positions and the climate was different, the birds may have had shorter trips between agreeable summer and wintering grounds. But as the earth changed, areas with the favored conditions grew further and further apart. The birds adapted, slowly developing the ability to survive the long commutes. Eventually, it became a routine part of life.

The tern isn’t the only long distance traveller. Animals ranging from giant humpback whales to tiny eels make massive journeys in search of food and mates. Some don’t eat for weeks or months while traveling, plumping up before starting out and arriving exhausted and hungry at their destinations. Others snack along the way, stopping now and again for a rest.

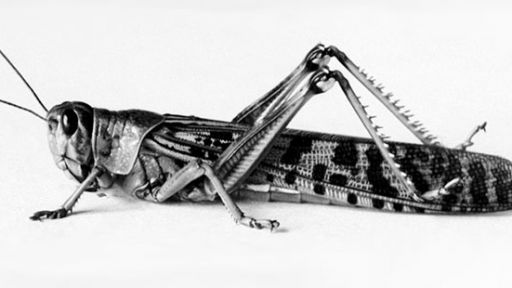

But some animals, particularly smaller ones, don’t migrate very far at all. There are insects, for instance, that may simply move from the top of a tree to its base when the weather changes. And some seashore species that live amidst the waves, such as lobsters and urchins, may move just a few hundred feet offshore when the pounding storms of winter arrive. Similarly, some tiny coral reef fish may move into deeper or shallower water, depending on the season. But these “micro migrations,” as one researcher has called them, are no less important than the longer ones — just shorter.

It takes generations of monarchs to complete a journey. Other migratory species have discovered ways to almost completely do away with their annual trips. In suburban areas with plenty of bird feeders and ornamental berry bushes, for instance, some birds don’t need to go anywhere to find enough food. As a result, a few birds that might once have moved south for the winter now stay to brave out the colder months. Similarly, ducks and geese that once honked their way north and south now stay on some ponds year round, waiting for the daily visits of bird-fanciers with bread crumbs.

Will such cushy lives dull the senses of these stay-at-homes, making them unable to migrate should conditions change? Researchers aren’t sure. But there is evidence that it can take hundreds of years for wild animals to lose the instinct to migrate. Some farmers, for instance, say their herds of cows and sheep become fidgety at the change of season, perhaps driven by a buried urge to find greener pastures. And some researchers suggest, mostly in jest, that a “migration gene” explains why some people like to set off on globetrotting expeditions, while others prefer to hang out near home.