Craig Packer is a Professor at the University of Minnesota’s Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior. Research interests include ecology of infectious diseases, ecosystem processes in African savannas, and conservation strategies for mitigating problem-animal conflicts. Packer is the Director of Lion Research Center and a co-founder of Savannas Forever Tanzania (SFTZ). Packer received a J.S. Guggenheim Fellowship in 1990, became a Distinguished McKnight University Professor in 1997, and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2003. He is the author of “Into Africa,” which won the 1995 John Burroughs medal, and more than 100 scientific articles, most of which are about lions.

How did you first get interested in lions and how long have you been involved in lion research and conservation?

I took over the Serengeti lion project in 1978. I was first attracted to lions by their reputation for cooperation and the fact that they are the only social cats.

Why do you think there has been historically less attention given to lions than other species that are facing population decline?

They are found in most East African and South African parks and reserves and they are much easier to observe than, say, leopards or any of the other wild felids. But it has taken time to realize that the tourist areas of the major parks are about the only place where lions are reasonably well protected – so they are no longer the tip of the iceberg but pretty much the only lions left in the wild.

What are the primary factors that have attributed to the decline of lion populations over the past fifty years?

Loss of prey, persecution in retaliation for cattle killing and man-eating and sport hunting.

You conduct daily monitoring of lion populations for research purposes. How do you track the lions and what have you learned about the species through this process? How does monitoring lions help in your conservation efforts?

We have discovered why lions have manes, why they live in groups, why they nurse each other’s young, why they do (or don’t) hunt cooperatively, and what regulates their population size in natural ecosystems. By monitoring the lions on a daily basis we have also been able to document the effects of close inbreeding, identify the diseases that threaten their health and measure the extent to which local people kill lions in retaliation for livestock losses.(Find out more.)

Why is there a growing risk of inbreeding among lion populations? Why is this harmful to the species and what can be done to prevent it?

As the lions inside national parks become cut off from larger populations they inevitably start breeding with their close relatives. This increases the risks that harmful genetic variants will be expressed in their offspring and reduces genetic variability. We suspect that the lion population in Ngorongoro Crater is adversely affected by inbreeding through an increased susceptibility to infectious diseases.

What are human-lion conflicts? What can be done to limit or assuage these types of conflicts?

Lions eat thousands of livestock and may attack over a hundred people in Tanzania each year. It is essential to improve livestock husbandry practices so that people don’t need to retaliate in the first place. In places with high levels of man-eating, we have found that the lions are drawn to agricultural areas in pursuit of bush pigs – a nocturnal crop pest. Poor farmers sleep in their fields to protect their crops against the pigs, and the lions stumble on to an opportunity for an easy meal. We are exploring cheap ways to exclude bush pigs from agricultural areas.

Is it possible to regulate trophy hunting in such a way that it would have low-impact on lion populations?

Trophy hunting has a greater impact on lions than on buffalo or impala because a male lion is someone’s father and female lions spend two years rearing each litter. As long as dad remains with his pride, his cubs are reasonably safe. But replacement males refuse to be step-fathers and instead kill cubs so as to be able to mate with the females right away. So by killing the keystone individuals in each pride, trophy hunters may end up causing the death of the next generation. Because males generally take over their first pride by their 4th birthday and it takes 2 years to successfully rear a set of cubs, males shouldn’t be “harvested” until they are at least 6 yrs of age. Unfortunately, lion trophy hunters have routinely shot males as young as 2-3 yrs of age and have therefore had a serious impact on lion populations throughout Africa.

What work are you doing with the Whole Village Project? How does this work relate to your work with lions?

The root cause of the Conservation Crisis in Africa is rapid human population growth. The population of Tanzania has quadrupled since I first went to work with Jane Goodall in Gombe in 1972. The growing rural population needs to eat, thus large tracts of wildlife habitat have been converted to agriculture and bushmeat remains an essential source of animal protein in many parts of the country. But we are nearing the point of no return, and I doubt that many of Tanzania’s game reserves and national parks will remain viable 100 years from now. The one sure way to reduce human population growth is economic development. Currently 90% of Tanzanians live in poverty and the growth rate is nearly 3% per year. Whenever a nation crosses a threshold in economic development, people reduce their preferred number of children from about 6-8 kids to only 2 or 3. This is called the “demographic transition” and it is the only hope for African wildlife. I helped start the Whole Village Project because numerous well-intended, well-funded economic development projects are being implemented in rural Tanzania – but their outcomes are not measured. Time is short and the development agencies need to be as effective as possible, so we are trying to develop a system whereby their impacts can be measured objectively.

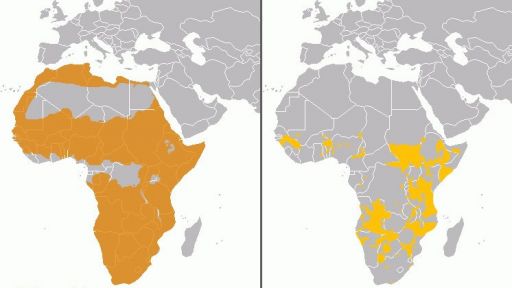

Are there specific areas in Africa that researchers and conservationists are targeting to carry out their work? Why?

There are four key ecosystems where lions must be protected if the species is to survive for the next hundred years: Kruger National Park in South Africa, the Okavango Delta in Botswana, Serengeti National Park in Tanzania and Selous Game Reserve, also in Tanzania. Each of these reserves still holds over 1,000 lions (large enough to prevent risks of inbreeding and to withstand environmental perturbations) and their associated herbivore communities are safely protected. If these four areas can be protected, the lion will be far better off than tigers. But while Kruger, Serengeti and Okavango are reasonably well managed, the Selous relies on revenues from trophy hunting and is seriously underfunded.

George and Joy Adamson were big proponents of taking previously captive lions and reintroducing them back into the wild. What are some of the strengths and weaknesses of rehabilitation programs?

Lions can only survive in areas with adequate prey and no human persecution. If lions have been eradicated from an area, the source of the conflict must be resolved before attempting any sort of translocation. Finally, the lions must be completely self-sufficient and must not view humans as a source of provisions or comfort. This eliminates any sort of return to the wild by captive-born animals.

Lion translocation has been highly successful in South Africa where dozens of former cattle ranches were returned to their natural state, first as game ranches then as fully restored wildlife areas. The first step of these translocations always started with a lion-proof fence and the complete approval of the communities surrounding the reserves – with the understanding that the lions would be destroyed if they escape. Importantly, though, these always involve wild-caught lions.

Do you consider George and Joy Adamson the first modern-day lion conservationists? How has their work impacted future generations of lion experts and conservationists?

The Born Free story has certainly inspired numerous imitators, but I’m not aware of any cases where the captive-born lion successfully survived. Some were shot by trophy hunters, some were killed by poachers, some had to be destroyed after attacking people. Translocation works because it focuses on re-establishing lions in a well-defined area using wild-caught lions. Rescuing a captive lion fails because it tries to make a sow’s ear out of a silk purse.

Do you remember when you first learned about Elsa? Did her story affect you or change your perception of lions at the time?

I was a kid when the film came out and I remember thinking that the theme song was rather pompous and corny. Then I met Bill Travers on the plane to Kigoma during my first trip to Gombe in 1972 and heard a lot about George Adamson’s later re-introduction projects in Kora from friends in Kenya in 1978. Elsa’s cubs were released into the Serengeti in 1961 and though Adamson thought he might have seen “Little Elsa” in the following year, it’s likely that they were all killed by Serengeti lions shortly after release. Lions are highly territorial and readily attack strangers; young nomads seldom survive after leaving their natal prides.

Do you think the Born Free story perpetuates a kind of myth about wild animals and our relationship to them?

Biographical stories always seem to resonate with the general public whereas concerns about populations and habitat seem to leave people cold. Best of all, Born Free involved people touching lions and somehow made it seem like we can fix nature if only we prepare enough chicken soup. Politics, villages, broad swathes of wild Africa – these are much harder to manage. But if the world can’t find ways to protect a place like the Selous, you can forget about the lion, no matter how many cute cubs we cuddle.

Finally, what are some of the things that people can do to help save Africa’s wild lion populations?

Rural poverty in Africa is a profound moral challenge with enormous implications for global health and security. If Africa can develop economically to the same extent as Asia and Latin America, the resultant drop in human population growth would reduce pressure on Africa’s savannas and wildlife. Lions breed like rabbits, as long as they have a safe place to live. There are still a few places in Africa with 20,000-55,000 km2 of healthy habitat. Keep these large parks intact until the next millennium, and the lion will go on forever.