TRANSCRIPT

[ethereal music] - [Narrator] They're ancient creatures in a changing world.

These evolutionary gems have been around since before the dinosaurs, but suddenly, they're slipping away.

As scientists race to find answers, amphibians are vanishing.

- [Speaker 1] We're going to lose perhaps half of the amphibians species and they go away for good, they don't come back.

- [Narrator] The implications are enormous.

- [Speaker 2] Some of these habitats will fall apart without their amphibians.

- [Speaker 3] It's an indication to us that there's something wrong.

At what point are we gonna turn around and say, "Well, hang on, we needed those frogs"?

- [Narrator] Across the globe, amphibians are walking a thin line.

If we act quickly, we might pull them back from the edge.

- [Speaker 1] This is the only chance we have.

[ominous music] [upbeat music] - This program was made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

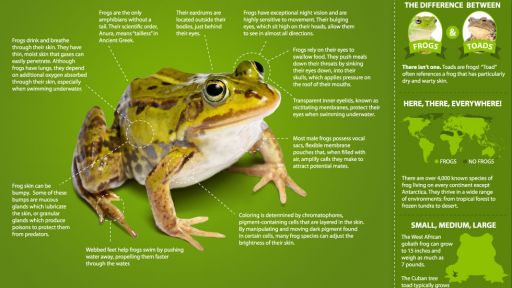

[ethereal music] - Frogs have managed to navigate life on earth for more than 250 million years.

They were the first of our ancestors to venture from the water to the world beyond.

But their fish like beginnings haven't hindered their progress on earth.

They've evolved into an explosion of species, each one unique.

These diminutive time travelers survived the dinosaurs, asteroids, and ice ages, adapting in ways that boggle the mind.

Some are masters of camouflage, while others avoid predators by carrying poisons in their skin.

Their survival tactics have splinted them into thousands of species scattered on almost every corner of the earth.

Whether salamander, frog, or toad amphibians are some of the most diverse and far flung animals on the planet, but they're disappearing and experts are worried.

Frogs are considered bellwethers for the environment.

Their double life makes them unique.

It's through their skin that they breathe and drink.

Because their skin is so permeable, they're especially sensitive to changes in the environment.

Today, more than a third of amphibians are in decline.

From Australia to South America, frogs are disappearing.

Why are species that have survived for eons suddenly collapsing?

Scientists are searching for clues before the next species slips away.

Frogs can be secretive, to find answers, one must probe the shadows.

[nature sounds] This glass frog's, translucent skin reveals her eggs.

Coupling can be a dangerous proposition.

Frogs and their offspring are key players in the food chain.

The parents will go their separate ways leaving their eggs to fate.

On a nearby leaf, another frog looks similar, but his species has a different tactic.

This father will stand watch over his young until they hatch.

He'll guard them night and day.

The extraordinary life history of amphibians has played out like this for millions of years, but conditions are rapidly changing.

Whether deep in the rainforest or on a sandy outcrop at the ocean's edge.

On the tip of Cape Cod, life is stirring with the first spring rain.

Spadefoot toads sprout like strange flowers from the sand.

They'll make their way to vernal pools delay their eggs.

If toads can't get to their breeding ponds, the population will gradually vanish.

In the northeast, spadefoot toads are being edged out by humans.

Here at the Cape Cod National Seashore, the land is protected, but the roads can still take a toll.

Amphibians all over the world face a deadly collision course when their habitat is carved up.

If a female is full of eggs, the next generation is lost as well.

Cape Cod National Seashore has begun to take precautions on warm rainy nights.

Every little effort makes a big difference.

Millions of amphibians are lost each year when they collide with humans.

How many millions of roads crisscrossed the globe?

Human population has doubled in the last 50 years, amphibians are getting hit from almost every front.

These super survivors can't evolve quickly enough to keep up with the changes.

We've stirred up the perfect storm for frogs.

Add a mysterious disease to the mix and the situation becomes critical.

We're now losing frogs even in the most pristine corners of the earth.

In Yosemite National Park, the mountain yellow-legged frog has maintained a foothold for millions of years.

They've survived ice ages and glaciers.

Even their tadpoles are tough enough to weather multiple winters until metamorphosis.

But today they're in trouble and experts have been struggling to figure out why.

Dr. Roland Knapp was one of the first to identify one of the causes.

- [Dr. Knapp] Historically, there were lots of frogs here.

Records suggest that walking along the lake shore, you would just see frog after frog plopping into the water, and now you can walk the entire lake shore and not see a single frog.

In the beginning of the 19 hundreds, to create recreational fisheries, people began moving non-native trout into many of these naturally fishless lakes.

Trout prey on the frogs, and in most of these places, the frogs are now gone.

- [Narrator] Knapp has been part of an intensive effort to remove fish from Yosemite's lakes.

It looked like the frogs were making a comeback until they fell prey to something even more insidious.

- [Dr. Knapp] It wasn't long after we began the fish eradications that we realized that there was something else going on besides just fish, and that something is the amphibian chytrid fungus.

- [Narrator] 12 Years ago, Knapp started finding dead frogs at his study sites.

At first, the deaths were a mystery until a strange fungus was identified, it seems to attack the skin of a frog, depriving it of oxygen.

- [Dr. Knapp] It's really hard to see an animal that you've tagged, you've recaptured several times, you've watched them for hours sometimes, and then you find that same animal dead in a pool.

This disease is taking the species out.

- [Narrator] In a matter of decades chytridiomycosis or chytrid, has become a global epidemic.

- [Speaker 1] It's almost like we're seeing the yellow fever of frogs or the flu of 1918.

We haven't figured out how this disease even works, how it spreads so quickly.

- [Narrator] At UC Berkeley, Mary Styce is trying to uncover more clues about chytrid.

- [Mary] These little circles are zoospores, and that's the infectious stage of the fungus.

It swims through the water looking for its next victim, a tadpole or an adult frog.

The most puzzling thing about this disease is that we have no idea where it's from.

It's found in preserved specimens from the 1930s in Africa, from the seventies here in California, but it looks like it's a new disease moving into populations.

Up in Yosemite where I do my field work, it's looking pretty bleak, I am really worried.

- [Narrator] We know that the fungus needs water to survive.

It also needs a host, but we don't know how it moves or how to contain it once it arrives.

- [Dr. Knapp] Unlike the fish where we actually had some control over those fish populations and we could remove them from selected lakes, we don't have that ability with the amphibian chytrid fungus.

All we can do right now for the most part is watch it do its thing.

This is a frog that has incredible staying power.

They're incredibly well adapted to this harsh environment, and now, on our watch, they're disappearing.

- [Narrator] The team is rushing to collect as much data as they can, but chytrid is a puzzling enemy.

While some species appear to be resistant, others are being devastated.

The mountain yellow-legged frog is losing ground fast.

- All right, 57.

- [Narrator] The fungus that causes chytrid known as BD, can extinguish a population in a matter of months.

It seems to thrive at high altitudes where it's cool and moist, but no one knows how it travels or how to stop it.

The disease is sweeping through the Sierras.

It's well established in Mexico, and it's been moving through Central and South America, devastating amphibians.

- [Dr. Lips] Central and South America harbored 50% of the world's amphibian species.

This was the place with the greatest amount, and now we've potentially lost a huge portion of that.

- [Narrator] In Costa Rica, Dr. Karen Lips was one of the first to witness a mysterious die off of frogs.

- [Dr. Lips] One day I was walking down the stream and I found a dead frog, and I was a little concerned, but over the next couple weeks I found a couple more.

I went back the next year and they were gone.

The frogs had disappeared.

Essentially, the same story played out a couple years later across the border in Panama.

- [Narrator] While Lips was witnessing die-offs in Central America, a similar story played out in Australia.

By the time chytrid was identified, amphibian populations had already crashed throughout the world.

The fungus has been stealthy reaching into untouched areas that hold some of Earth's greatest treasures.

Frogs might be diminutive, but the stakes are enormous.

Medical science has begun to realize that frogs are little gold mines.

To ward off infection most frogs secrete chemicals from their skin, they can actually be poisonous.

These bright colors are a frog's warning to predators that they could be a dangerous meal.

The compounds on frog's skin have turned medical science around.

An extract from the skin of this little frog blocks pain more effectively than morphine, and it's not addictive.

The properties of frog's skin are being explored for everything from treating infections to preventing HIV.

We've just begun to mine these little treasures, and now they're slipping away faster than we can study them.

But the impact on earth's ecosystems is even more troubling.

Karen Lips has returned to her former study site in Central Panama to measure the changes.

Without the frogs, there's an eerie silence.

In El Copé reserve a concrete statue may be all that remains of Panama's spectacular golden frog.

- [Dr. Lips] Before the big crash this was a great place.

I think our total list here was something like 64 species of amphibians.

It didn't matter really where you went in the forest.

You would find 'em on the ground on the leaves.

You'd hear 'em up in the canopy.

You could walk any trail, any stream, and you would hear frogs calling day and night, and now there's just nothing here anymore.

- [Narrator] Chytrid is having a domino effect.

Frogs sit right in the middle of the food chain.

Without them, other creatures are disappearing too.

- [Dr. Lips] We're just beginning to understand what a forest is like and how it functions without frogs.

Ever since all the tadpoles disappeared, these streams have been really slippery and there's green algae growing all over the place.

That's just another example of the big changes that we see after all the frogs that tadpoles disappear.

The tadpoles not only eat the algae, but they also disturb all the sand and the mud, and so all that gets flushed out with the current and now there's no tadpoles, we see changes in some of the insects as well.

We're seeing lots of big changes in these ecosystems.

It's affecting fish and water quality, snakes, birds, you name it.

Basically everything we've measured has changed.

- [Narrator] Chytrid is on the move, while it's sweeping down through Central America, it's also traveling North from South America.

There's only a small area left in Panama that still seems to be chytrid free.

Two hours south of the Panama Canal there's a small patch of forest called Burbayar.

For the frogs here, life plays out as it has for millions of years.

While chytrid draws closer, miracles are still unfolding.

This father has been guarding his young for two weeks now.

The tadpoles on a nearby leave don't have a guardian.

They're more mature, but still days from hatching.

A healthy habitat is full of predators and pray.

No matter how big or small, every creature plays a role.

The forest holds thousands of insect species, some can destroy an egg clutch in a matter of hours.

Even if an intruder doesn't have a taste for eggs this father is fiercely protective.

Though the other species doesn't guard its young, it's developed another defense.

When attacked the tadpoles will break free, giving them at least a fighting chance.

Here in the stream, the tadpoles will spend most of their time feeding on algae in small plants.

A fantastic array of survival tactics has allowed frogs to brave the millennia, but chytrid is a predator like none other, and it's moving in fast.

- [Dr. Lips] The clock is ticking, and that's really what it's felt like more than anything since that first frog in '92 is the rush.

The rush to get out, to do as much as you can before another site goes.

- [Narrator] Lips and students have established a new study site here at Burbayar.

They're hoping that chytrid and the BD that causes it haven't arrived yet.

- [Dr. Lips] We're here to try and get more data to figure out what is happening.

How does this thing get around?

Can we stop it?

- [Narrator] The forest appears to be healthy with frogs, and insects, and snakes, but for how much longer will it remain intact?

- [Dr. Lips] We're running out of places where frogs are healthy.

We estimate within 10 years all of Panama will be gone.

We're talking upland areas, but as fast as you move, it's continuing its passage.

- I got a frog.

- [Dr. Lips]} As soon as we catch a frog, we take its body temperature because there's a debate about climate change and how it's affecting frogs.

33.5, ext we're gonna swab it and we'll send this sample off to the lab and they'll tell us whether or not this frog is infected with BD.

All right, so we're just gonna take this little Q-tip, swab the frog.

We do his belly, we do his feet.

If there's any BD, it'll pick it up and we send this off to the lab, and the lab will tell us if BD's on this frog.

- All right, I'm gonna let you go, buddy.

- [Dr. Lips] We think this site is still clean.

Look at that, that's [indistinct].

They're really rare, that's a big one.

They're a frog eater, he's out foraging and you can see him tongue clicking.

- [Narrator] Once chytrid arrives, this snake may well disappear along with the frogs.

Based on what Lips finds here, they might take emergency measures.

- [Dr. Lips] If we have to, we will put some frogs into captivity as a safeguard against the eventual arrival of the fungus.

- [Narrator] This is exactly what took place in Central Panama three years ago.

With chytrid fast approaching biologists evacuated frogs from the surrounding forest.

These refugees are so close and yet so far from their cloud forest.

At the foot of the mountains sits a humble building that's serving as an arc.

The El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center is an international project launched by the Houston Zoo.

EVACC shelters 58 species of frogs, some of the rarest on earth.

This beautiful golden frog is unique to Panama.

It lacks eardrums and communicates by waving its arms.

They're considered good luck by Panamanians, but because of chytrid, they may be gone from the wild.

Edgardo Griffith runs the center with his wife, Heidi Ross.

They have to try to replicate the cloud forest light, temperature, humidity, everything has to be right.

And feeding so many mouths is a never ending challenge.

- [Heidi] We just rinse some off just because the worms might have chytrid on them.

- [Edgardo] We try not to put anything like dirt without disinfected before we put it inside the building.

- [Narrator] Everything entering EVACC has to be chytrid free.

Every person, every worm, every rock, and plant.

These horn tree frogs mimic leaves in the forest.

Even the froglets are brilliantly disguised, but the best of camouflage can't protect a frog from chytrid.

In the quarantine room, new arrivals are put through a grueling process.

We don't yet know how to rid a habitat of chytrid, but individual frogs can be treated.

- [Edgardo] It's okay, my friend, it's okay, it's okay.

Look at you.

When we started collecting the animals in 2006, we lost 50% of them.

These frogs can live for years and probably 20, 25 years.

The treatment equivalent would be for a person going under chemotherapy.

I will leave it there, you sit there for 10 minutes, It's a very invasive process because we have to keep the frogs in contact with this solution, which is a really strong solution, for 10 minutes, for 10 days.

I'm pretty sure that she doesn't like to be in that little cup with that nasty solution.

But something that tells me that she knows somehow that we are trying to help her.

For most people, they wouldn't think that this is important 'cause this is a brown, bumpy, little ugly frog.

But this animal here is telling us that we are doing something wrong.

- [Narrator] At EVACC, success is measured by egg clutches and tadpoles.

They recently celebrated the first golden froglet to metamorphose, but there are also the inevitable setbacks.

- [Heidi] It's over here.

- [Narrator] This was one of the center's first rescues.

- [Edgardo] There's always parasites and such lined up just waiting, so the first mistake that will show us that we are not doing things right.

- [Heidi] Once they present the symptoms, it's oftentimes too late.

- [Edgardo] See this?

- [Heidi] Oh my gosh, there's a gigantic parasite that was internal.

When the host died, I'm sure the parasite came out.

- So many things that we don't know about these animals, so many new species of parasites we can never get used to things like this happening.

- [Narrator] The ultimate goal is to return these frogs to the wild someday Scientists are working to find ways to control chytrid in the environment, but for now, it's still a distant dream.

And things in El Valle are changing quickly.

Housing developments might be rewriting the future for Panama's frogs.

- But they're develop in this area.

Last year I came this way and I got lost, so many new roads here that I didn't even know where I was going anymore.

Less than a year ago, there was only one road.

Two years ago when we started the EVACC project, we came here and we collected some frogs from this particular place and in less than a year they clear the whole thing.

This is gonna be somebody's house.

I feel just panic 'cause when I look up that way, there's a lot of forests, but the same thing that happened here can happen to that forest in less than a year.

It doesn't matter how many safe, healthy frogs we have at the center.

If habitat loss continues, where are we gonna put the frogs in the future?

If we figure out how to help them so they can fight their fungus in the wild?

There's not gonna be a place for the frogs anymore.

- [Narrator] There is hope that a few individual frogs might be resistant to chytrid, but runoff from the development is making the stream unhealthy for frogs.

- [Edgardo] I will never give up.

I will still come every time when I have the opportunity because there's always a possibility for us to find frogs.

That's one of the things that morning you think about it.

- [Narrator] Chytrid has been devastating, but it's by no means the only threat to amphibians.

In parts of the US where frogs haven't been lost to the fungus, they're being hit by other forces right here in our own backyards.

In Minnesota, 13 years ago, a group of school kids took a field trip to look for frogs.

What they found was the stuff of nightmares.

They found frogs with extra limbs, missing limbs, deformities that seemed to defy nature.

Similar reports began to surface from around the country sounding an alarm.

At Yale University.

Dr. David Skelly and his students have been collecting deformed frogs for the past eight years.

Their findings have disturbing implications for frogs and humans alike.

Scientists have discovered that a kind of parasite can cause multiple limbs, but Skelly is concerned about other deformities that have yet to be explained.

- [Dr. Skelly] This is a leopard frog and this is what happens when they're infected with a parasite called Ribeiroia.

This is one of the causes for limb deformities in the natural world.

While the animals with the extra legs get a lot of attention, this is the animal that really concerns me.

This is a leopard frog metamorph as well, and it's got only one hind limb.

This is the animal's tail here.

What makes these animals so significant is we really don't know what causes these kinds of deformities.

The parasite is not found where this frog was collected, so that can't be what's going on here.

It's gotta be something else and we don't know what it is.

- [Narrator] Skelly has been looking for answers in some unlikely places.

Here in suburban Connecticut, he's finding that life might not be as sheltered as folks once thought.

The average resident might be hastening the demise of frogs while they undermine their own health.

- [Dr. Skelly] We started sampling this pond a few years ago and we're finding reproductive deformities in the frogs.

- But there's another one.

- In suburban ponds like this, we're finding that about 21% of all the frogs have deformities that is male frogs are growing eggs inside their testes, and that is not normal at all.

- [Narrator] The duckweed that's choking this pond is probably caused by chemicals like fertilizers, but Skelly is also concerned about compounds that are less conspicuous.

- I think a lot of people don't realize that when they use chemicals or if they flush medications down their toilet, that it could end up passing right out of the house, right through a septic field, and right into a pond.

It's just not something people thought about and to be fair, it's not something that scientists, and regulators, and policy makers have thought about very much either.

All of that water collects in these basins.

Things like medications, there are a huge range of drugs that people take and many of them leave our bodies intact.

We're starting with the most obvious candidate, birth control pills.

We know in the laboratory that synthetic estrogen can cause these kinds of problems.

Now we just need to figure out if that is what's going on in places like this.

- [Narrator] Skelly's alarm is shared by Dr. Tyrone Hayes at UC Berkeley.

- [Dr. Hayes] If an entire class of animals that's been around for millions and millions of years is rapidly declining and potentially going extinct, we really need to think about what we've done and if our advances will eventually harm us all.

I really like the science.

I like solving the puzzle, I like the CSI.

I also like frogs and so I also feel a real drive to help understand how pesticides and other chemicals are affecting amphibian populations.

- [Narrator] Hayes and his students have been looking for clues in the Salinas Valley.

- [Dr. Hayes] 50% Of the USS Agricultural products come outta California.

It's something like 85% of the country's lettuce come outta Salinas, 90% of the almonds, it's called the salad bowl of America.

California uses more pesticides than any other state.

The second biggest is Florida.

Things like chloropicrin that's used out here in the strawberries.

Chloropicrin is a nerve gas.

These are guys who are applying it, they're out there picking it.

Methyl bromide is a fumigant, something they pump into the soil.

What are some of the other big ones you guys?

- Diuron.

- Diazinon.

- [Dr. Hayes] This will all end up in the river that we're working in here.

It might look like we're out in the bush somewhere, but 15 feet on either side, we're surrounded by agriculture and the runoff ends up in this river.

All of the algae as a result of all the nutrients, 'cause a lot of fertilizers are used in agriculture, and once those fertilizers get into the water, you get these blooms of algae.

I wouldn't say it's a sign of a healthy river.

This is a site where we typically find compromised immune systems, tadpoles that aren't able to fight off disease.

Our data so far suggests that the mixture of pesticides causes and increase in stress hormones and those stress hormones cause immunosuppression, which leads to the inability to respond to any kind of disease pathogen.

- [Narrator] While investigating chemical runoff, Hayes stumbled on another culprit.

- [Dr. Hayes] We started going to Salinas River looking for the native red-legged frog and it turns out that it has been completely replaced on the river by bullfrogs.

This invasive bullfrog itself is one of the causes for a decline in many of these areas.

And so we're studying them in areas where they're not doing well to try to understand what may be driving some of the native species to extinction.

- Entrepreneurs transported Bullfrogs from the east coast hoping to farm them for food.

Instead, they unleashed a carnivore that has decimated California's native frog.

- Six, 25.

- [Narrator] It seems that even the tough bullfrog isn't doing so well with the toxins in this water.

- Did you take that out?

- [Narrator] Back at Berkeley, Hayes is studying another non-native.

African claw frogs were once used in human pregnancy tests, but when they became obsolete, many were discarded.

These were collected from streams around California.

- [Dr. Hayes] We're removing an invasive frog and we're studying them to try to understand declining amphibians.

- [Narrator] Hayes is testing the effects of chemicals like atrazine, a common herbicide.

- [Dr. Hayes] We have a whole family of animals where we've eliminated the female chromosome.

- Specimen zero one.

- [Dr. Hayes] These animals that we know are genetic males have been exposed to atrazine for their entire life, and many of these genetic males now are turning into females.

You can see he's got eggs that look like they're in a sack.

These are actually yoked eggs ready to be laid.

What's happening is you're skewing sex ratios.

You can get genetic bottlenecking, which can cause crashes and quite frankly, if you're a genetic male, it'd be nice if you're developed as a genetic male.

And now we have a chemical, very common and the environment that's effectively sex reversing animals.

I'm gonna show you something pretty amazing, scientifically speaking.

The one that's sort of remarkable is this pair.

These are both males, the one on the bottom acting as the female we affectionately refer to as Darnell.

He's a genetic male that not only acts like a female, he lays eggs like a female.

He, she has been exposed to atrazine all of her, his, her life, I don't even really know how to reference it.

This is Darnell's third clutch.

So Darnell has sons and daughters that we've grown up.

You can see eggs in the bottom.

This is actually her second clutch for today.

He, she has been copulating for getting close to 24 hours now.

This is probably one of the most remarkable things I've seen in my work.

But I personally have mixed emotions.

I'm very excited about the science and trying to understand the mechanism, but on the other hand, I am worried.

This is the most common contaminant in ground and surface water, and drinking water.

And the level of atrazine that it took to make this male turning to a female is three times less than what's allowed on our drinking water.

I really think that the global amphibian decline is telling us something about human health.

- [Narrator] The toxins in our waters are reaching well beyond frogs.

Reproductive abnormalities have been reported in everything from alligators, to polar bears, to humans.

- [Dr. Hayes] It's not just a problem with frogs we should be concerned about.

The water that's causing their problems it's the same water that we're drinking and using to water our crops.

- [Narrator] Frog or human, we all breathe the same air and drink the same water.

For their sake and ours, experts agree, we have to take action and there's no time to lose.

Australia has been hard hit by the deadly fungus, chytrid.

Seven species have been lost and more are on a fast track to extinction.

Now, add climate change to the mix.

Australia is experiencing its worst drought on record and amphibians are feeling it.

In the South, a population of Booroolong frogs was evacuated when their river dried up.

Jerry Marintelli has been breeding the frogs to hedge against climate change.

- [Jerry] We have some good eggs here.

They are fresh, but they're good, some new ones.

- Just outside of Melbourne, Marintelli and his wife Erica, have created an unusual arc.

- [Jerry] We couldn't afford buildings when we started and we thought, what do we do?

We bought shipping containers.

Shipping containers like this are waterproof and insulated and we can convert them into a perfectly useful lab for these frogs.

Installing irrigation systems, all the things that the frogs need, but they're a fraction of the price.

And to top it off, they're portable so we can ship them anywhere in the world where frogs need help.

- [Narrator] Here at the arc, our Australia's most endangered frogs, the booroolong frog, the spotted tree Frog, and the extraordinary corroboree.

It's name is an Aboriginal award for celebration or gathering where the elders often wear black and yellow paint.

Corroborees used to be plentiful, but chytrid has pushed them to the edge.

The Merintellis are vehement about returning frogs to the wild.

- [Jerry] The quicker we can understand the problems they face, fix the problems, and get these frogs back into the wild, the better.

They can't live in a fish tank for a hundred years.

We disrupt the things that eat the frogs, the things that the frogs eat.

They are part of an ecosystem and this tank is not an ecosystem.

- [Narrator] These little frogs are headed back to their stream.

The drought has finally broken, at least for now.

- These are booroolong frogs from Burrowye Creek.

So with climate change, Burrowye Creek dried up in the last drought, so we had to bring them into captivity and breathe them.

And these are all the young ones that we're taking back to Burrowye Creek, and we've got a little bit over 500 frogs to go back.

Few of you back to Burrowye Creek tomorrow.

Are you excited?

Relax, you look excited.

For the booroolong frog climate change, warming conditions, and the prolonged drought, all of that came together and made the stream stop flowing.

The fact that those habitats are changing right now means something's going wrong, and that means we've gotta do something about helping the little guys.

Look at that.

You wanna see some booroolong frogs?

Have a look, you know what they are?

There's your new friends, you listen to them tonight.

- [Narrator] Marintelli has kept some frogs back at the center as a safeguard.

With climate change, they might need help again.

- [Jerry] Welcome home.

- [Narrator] They released some of the froglets in the afternoon light.

They'll share the rest with the locals.

- [Jerry] Not up there, the bird will eat you.

You go and find a little crevice, go home.

[indiscernible chatter] - Oh, look at this fat one, Harry.

- [Jerry] I love it when kids are looking at frogs.

- There, that's a huge fat one.

- [Jerry] That's what we do.

We feed them lots and lots and lots of crickets.

More crickets than you've ever seen in your life.

If they're not interested, then the project falls apart in 50 years.

Put the lid down on the ground there.

It's really important to make sure the community's on board, particularly when the community lives amongst the frogs.

Tip everything up and tip them out.

They're out there watching the habitat and they'll look after those creeks now that the booroolong frogs are back.

We're just the bridge across a bump for all of these frogs.

Whether it takes us a year to help them out, or 10 years or 20 years, we should always be trying to put them back.

- [Narrator] Even the most dire situation won't deter Marintelli.

These spotted tree frogs have been struck hard by chytrid.

On the stream where they once lived the fungus wiped out an entire population.

Only one male was spared.

With the help of captive females, Marintelli bred them back from extinction and three years ago they began returning frogs, despite the presence of chytrid.

Each spring, the team comes back to look for survivors.

- [Jerry] We have no other choice but to help these frogs develop resistance.

Even if we have to breed so many frogs and put 'em out there where 95% of them die.

Who doesn't die?

The resistant ones.

What we are trying to do is drive evolution so these frogs will be able to live with chytrid.

Don't you move Little froggie.

- You catch him?

- Yep, it's one of our babies.

- Like it a lot.

- This is where they were wiped out by the chytrid Fungus.

We've just brought a frog back from extinction.

You can't do much better than that.

They grew up in our lab, we put 'em back and we've been able to find them even two and three years after we've let them go.

To find them surviving with the chytrid Fungus shows us that we can put frogs back.

They can live here with the fungus and it gives us some real hope.

- [Narrator] It looks like the frog might be winning this round, but with pressures coming from so many directions, stemming the crisis means attacking it on every front, whether it's chytrid or habitat loss.

Here in the heart of Georgia, the Atlanta Botanical Gardens used to focus only on plants.

12 years ago, they decided to give amphibians some much needed help.

Today they house over 30 species.

Many of them rescued from Panama when chytrid swept through.

But these days some of Georgia's very own frogs are in trouble.

The gopher frog has lost almost all of its habitat.

To bring it back from the edge, the gardens is part of a Head Start program, they're raising froglets.

Now that they're past their most vulnerable stage, these little guys are about to hit the road.

They were raised from eggs by Robert Hill and now they're going back to the wild.

- [R. Hill] The gopher frog is right here on our own backyard.

That doesn't take millions and millions of dollars.

They just need a helping hand.

- [Narrator] John Jensen, with a Department of Natural Resources, knows that returning these frogs is not as simple as it might sound.

The gopher frog has lost 97% of its habitat.

- [J. Jensen] When you have 3% of this habitat remaining and all these animals that depend on it, it's obvious why they're disappearing.

- [Narrator] The Gopher tortoise also lives here.

Remarkably, the frogs share the tortoises burrows, which can reach 10 feet Deep.

Gopher frogs depend not only on the wetland but the surrounding forest.

Thanks to the Nature Conservancy, they now have nearly 2000 acres of protected habitat.

Now it's up to the frogs.

- [R. Hill] When you've spend a lot of time raising these little guys up from little tiny black dots in a jelly, it's like sending your kid off to school for the first day.

This is what conservation is all about.

It's not just keeping it alive in a zoo, it's breeding it and being able to put it back where it belongs.

- [Narrator] If we can ease at least some of the pressures on frogs, we might be able to help them weather the storm.

Back in Yosemite Knapp has decided it's time to take some chances with the mountain yellow-legged frog.

A few populations seem to be holding their ground with the fungus.

Could they be resistant?

And if so, could they recolonize some of the ponds where the frogs have been lost.

Knapp feels it's worth taking the risk.

The team is collecting frogs from a healthy population to relocate them.

- [Dr. Knapp] We're gonna be moving these frogs five or six miles to some new sites, and then we'll return to those lakes throughout the summer, recapturing those frogs, and then swabbing each frog.

Trying to get a sense of how well they're surviving in that new environment.

- 10.5.

- [Narrator] Each one is swabbed for the fungus and given an ID.

- [Dr. Knapp] We insert this little tag that's the same tag that some people put in their pets.

It essentially gives each frog a unique identification number and that allows us to identify individuals through time.

It is a little nerve-wracking to move these frogs because chances are good in the next two or three years following their move to a new lake, they're all gonna disappear.

In the worst case scenario, sacrificing those individuals to learn something that might benefit the species as a whole and amphibians around the world as a whole.

But it's pretty hard to sacrifice those individuals.

They're not just a number.

- [Narrator] The frogs will be airlifted to the relocation site to avoid the stress of a five hour hike in a backpack.

Back in Australia, the race continues.

Chytrid has swept through these mountains.

Here in the Australian Alps, Kosciuszko National Park shelters the last of Australia's corroboree frogs.

Parks and Wildlife of New South Wales is on a mission.

With the help of Jerry Marintelli, they hope to save this remarkable species.

These little guys have survived the eons.

They outlived the dinosaurs, but now they're blinking out.

Fewer than 200 remain in the wild.

As an emergency measure, last fall, a thousand corroboree tadpoles were released into tubs of chytrid free water.

In these protected nurseries, it's hoped that the youngsters will make it through their most vulnerable stage and develop a resistance to the fungus in the wild.

Marintelli and Dave Hunter from Parks and Wildlife are back to see if any survived the icy winter.

- Oh, there's one.

Yeah, I see tadpoles here too.

- It's a huge relief.

- Little Tatties, Oh, well there's two in there.

- Oh, there's some in this one.

And lots of tatties in this one.

- And tadpoles here too.

- Fantastic, and tatties in this one.

- We're gonna save some of them and we're gonna save as many as we can.

I hope that we get it right before these guys go extinct.

We have to do something about fixing this problem.

If we don't do that as humans, then there's something wrong with all of us.

Everybody has to act locally to do something about it.

If we don't act now, there might not be time to turn it around.

It's incredibly sad to wander through a habitat and see where a frog once lived.

I've stood in streams that were silent and I've listened all over the world to places where frogs have vanished, and the the ghosts are there, I feel the ghosts of those creatures.

We just can't keep letting that happen.

- It's amazing, there used to be as many as 100 of these to every square meter, and I really hope one day I can bring my kids back here and find 100 to a square meter once again.

But it's not looking too good for this guy at the moment.

Good luck a little fella.

- This program was made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

[upbeat music]