Each January, the people of Kundha Kulam, a parched farm town in southern India, raise their eyes to the sky, searching for signs of life-giving rain. But they are not looking for clouds. They are watching instead for the birds that arrive on the vanguard winds of the oncoming monsoon. At the sight of the first flick of feather, the villagers breathe a sigh of relief, knowing that their crops will soon get a welcome drink.

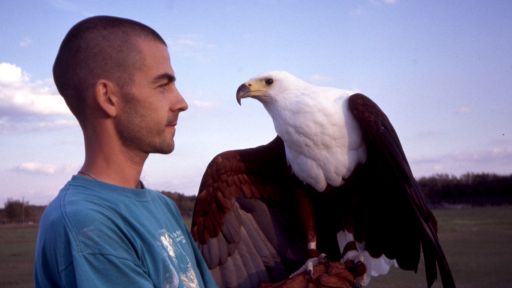

This week, NATURE takes you from Kundha Kulam’s vibrant monsoon marshes to the rugged American Rockies to explore the worlds of Extraordinary Birds. Along the way, viewers meet a Scottish father and son who have taken up the ancient hunting art of falconry, a performer who works wonders with a pretty smart parrot, and some senior citizens who have developed strong attachments to some feathered friends. There are also homing pigeons that deliver film, rat-catching barn owls that protect farmers from pests, and hummingbirds that show their prowess as long-distance flyers.

In each case, NATURE’s Extraordinary Birds highlights the intimate links that people have forged with birds. In Kundha Kulam, for instance, “if the birds come, we know we will be prosperous,” says a resident. Like the robin that is the harbinger of spring, or the lonely honk of a migrating goose that signals the arrival of another winter, the herons, ducks, and pelicans that swarm to the flooded fields around Kundha Kulam have become a powerful symbol of the cycle of life.

In many instances, however, birds are more than just symbols — they are companions. In a convent in New York state, for example, Sister Barbara Seaward has founded the group Feathered Friends. She, along with others in her community, conduct pet therapy sessions for those in nursing and retirement homes. The residents agree that there is nothing quite like a visit from a cockateil or a cockatoo to lift the spirits.

And in the whitewater rafting canyons of Colorado, guides use homing pigeons to safely deliver a valuable commodity — photos of customers splashing their way down the rapids — back to home base, so the keepsakes are waiting when the rafters return from their adventure. The flying film couriers have become an essential business partner.

In eastern India, homing pigeons play a different role: they are law enforcers. Despite the introduction of radios and e-mail, the state police force of Orissa still keeps nearly 700 pigeon police available to shuttle messages between far-flung stations, according to British Broadcasting Corporation reports. But the century-old pigeon force may not last long into the millennium, as budget makers are convinced the birds are no longer needed.

In Florida, however, sugar cane farmers are eager to enlist the aid of birds. With help from University of Florida researcher Richard Raid, who is featured on NATURE’s Extraordinary Birds, the farmers have encouraged ghostly-white barn owls to nest near their fields. The birds perform a valuable pest control service, with each nesting pair capable of catching and eating almost 3,000 rats a year. They are “nature’s rat traps,” Raid says. Each year, the rodents cost sugar cane farmers nearly $30 million in crop damage.

Like other birds, however, the barn owl is a powerful symbol for many. “Many people in the [Caribbean] islands and Central and South America believe that it is bad luck to see a barn owl, particularly during the day,” says Raid. “Rumor has it that to see one forewarns the death of a friend or a relative in the very near future.”

Despite their scary reputation, however, the once common owls are becoming endangered in some areas and need some human help, such as the construction of nesting and roosting boxes. Raid and his colleagues are testing models of barn owl boxes mounted on posts to see how receptive the birds are to such homes. Sugar cane grower Wayne Boynton, who has earned the nickname “Godfather of Barn Owls,” says owls have moved into all the boxes he has put up on his 3,000-acre farm. “It’s like [the movie] Field of Dreams,” he says. “If you build it, they will come. It’s that simple.”

Echoing a sentiment heard elsewhere around the world about other birds, Boynton believes that “you can’t have too many barn owls.” They are, indeed, extraordinary allies.