When it comes to zebras, it’s not all black and white. These spirited, striped African horses have rich, complex lives, as NATURE’s Horse Tigers shows. There are actually three kinds of zebras that wander Africa’s grasslands and forests. By far the best known and most common is the Plains zebra, the stocky little grazer often seen milling amidst the herds of wildebeest and giraffes in many a wildlife film. Less known and rarer are the Grevy’s and Mountain zebras, which despite similar striping live very different lives.

Plains zebras, for instance, live in highly organized social groups, with a stallion overseeing a small group of mares and their foals. As Horse Tigers documents, the stallions forge remarkably close ties with other males, routinely greeting each other with elaborate, rubber-necked embraces and toothy nips. The mares, in turn, forge their own alliances, staying together even if their stallion dies and is replaced by another. The whole group moves together, often migrating across vast stretches to find greener grass and water. The oldest females appear to lead the way, probably because they have the best memory of where to find the best pickings. Herds of 100,000 or more Plains zebras — which are found across much of Africa south of the Sahara desert — may migrate together, creating a remarkable natural spectacle.

In contrast, Grevy’s zebras live more solitary lives in the drier climates of eastern Africa. The mares do not form strong social bonds, and the stallions don’t keep a harem. Instead, male Grevy’s stake a claim to territory, and then seek to mate with females that move into the area. This distinctly different behavior is partly explained by genetics. Researchers have found that the endangered Grevy’s zebra — just 5,000 to 10,000 remain — are more closely related to wild asses than they are to the Plains zebra. One difference that is apparent at first glance is that Grevy’s zebras have slimmer stripes than their cousins on the plains, giving them a less brash and more sophisticated look.

Mountain zebras also sport a different look. In addition to its own distinct striping pattern, the Mountain zebra is built more like a donkey, with long ears and an extra flap of skin on its throat. One variety of Mountain zebra, the Hartmann’s zebra of southwestern Africa, once appeared headed for extinction, but its numbers have rebounded from less than 10,000 to more than 15,000 in recent years. Another variety, the endangered Cape mountain zebra, is found only in protected reserves in South Africa.

Why these three different animals evolved their striking stripes (which have made zebras a popular exotic farm animal) is a mystery. Some researchers believe the pattern helps protect the animals from predators such as lions and leopards, either by helping them blend into the background, or by creating a confusing, dazzling mass of color when zebras move as a herd. The flickering confusion makes it difficult for the hunter to home in on a single animal. Researchers do know that the stripes serve other purposes. You can, for instance, literally know a zebra by its stripes. Every zebra has a unique pattern that enables baby zebras — and keen-eyed researchers — to tell it apart from the others. Within species, however, the stripes can vary dramatically in their boldness and color.

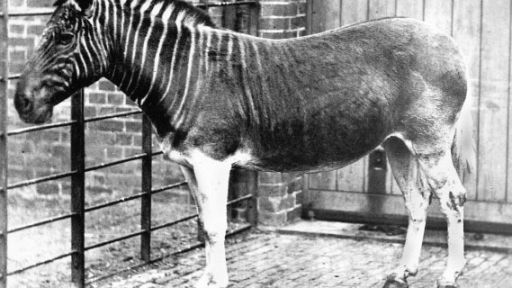

In some areas, for instance, Plains zebras may have no stripes on their bellies or legs. The variation, in fact, led some biologists to believe that there once was another kind of zebra — the Quagga, a brownish, lightly striped zebra that became extinct in the late 1800s and is now the focus of a restoration effort. The mystery of the Quagga and the marvels of zebra behavior continue to fascinate animal lovers and researchers alike. Some are focused on understanding how these Horse Tigers live, in order to protect them from hunters and habitat destruction. Others seek to document the many ways in which these sturdy animals have adapted to often harsh, unforgiving environments. Together, their observations are replacing our black-and-white images of these high-contrast horses with a colorful, detailed portrait of one of Africa’s best known animals. Online content for Nature’s Horse Tigers was originally posted August 2001.