In the late 1960s, whale biologist Roger Payne and several colleagues did something a little unusual, and it paid off with spectacular results. The researchers dumped a microphone into the sea, hoping to listen in on the underwater conversations that Payne believed whales were having. But “some people weren’t sure we were going to hear anything — they said it was just a waste of time,” Payne recalled to a journalist at the time.

It worked better than anyone had imagined, however, capturing a remarkable array of creaks, groans, and moans produced by humpback and other whales. Recordings of the whale songs were soon selling out at music stores, and people around the world were debating the meaning of the haunting melodies. The discovery earned the humpback a new nickname: “Songster of the Sea.”

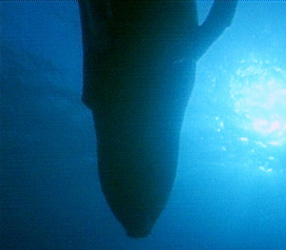

Today, scientists know more than ever about the song of the humpback. They know, for instance, that while both male and female humpbacks can produce sounds, only the males appear to produce organized songs with distinct themes and melodies, almost always on breeding grounds. As NATURE’s Humpback Whales shows, the males often sing while suspended deep below the surface, their long front flippers jutting rigidly from their sides. The songs can last up to 20 minutes, and can be heard more than 20 miles away. The male may repeat the same song dozens of times over several hours, and whales in the same geographic area sing in very similar “dialects.” Song patterns can change gradually over time, so that new songs emerge every few years.

Researchers still aren’t sure exactly how the whales produce the sounds. Whales don’t have vocal cords, so they probably sing by circulating air through the tubes and chambers of their respiratory system. But no air escapes during the concerts — and their mouths don’t move.

Scientists are also unsure about what the songs mean. Originally, observers believed they were a mating call, used to advertise the male’s availability to passing females. This idea was reinforced when divers observed other whales approaching the singers.

More recently, however, some researchers have come to believe that the singing humpbacks are actually issuing threats, not singing love songs. In part, that idea arose because scientists discovered that many of the whales approaching singers were other males, and the meeting would often end in a tussle. “It looks like the singing whale is telling the other males who is the boss,” says Gary Lyder, a whale biologist and whale watching guide.

Another recent theory is that the singing whales are simply finding out who is in the neighborhood, using the songs as a form of sonar for tracking nearby whales. But many scientists are skeptical of the idea, in part because the whales only seem to sing on breeding grounds.

Researchers may never be able to know for certain what the songs mean. But they continue to pore over recordings and replay the whale’s greatest hits. And in the meantime, the virtuoso whale singers continue to hit their high notes, serenading an unseen audience deep in the blue-black sea, returning again and again to the stage for haunting encores.