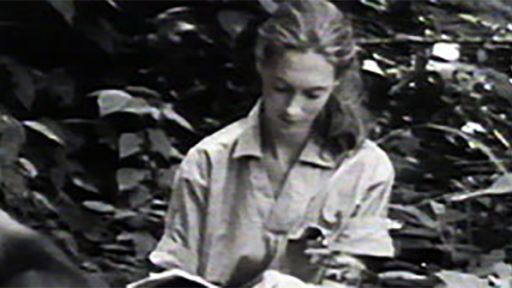

While we may believe that we have nothing but ancestors in common with our primate relatives, Jane Goodall’s research into chimpanzee behavior shows that, in areas from warfare to parenting, our two species are closely linked. For example, she found that, like us, chimpanzees create tools to make their lives easier — such as the carefully chosen grass stems used to “fish” for tasty insects, as shown in this NATURE program.

While we may believe that we have nothing but ancestors in common with our primate relatives, Jane Goodall’s research into chimpanzee behavior shows that, in areas from warfare to parenting, our two species are closely linked. For example, she found that, like us, chimpanzees create tools to make their lives easier — such as the carefully chosen grass stems used to “fish” for tasty insects, as shown in this NATURE program.

Goodall followed up this discovery with stunning evidence that the seemingly peaceful chimpanzees in fact systematically hunted smaller primates, such as colobus monkeys, for meat: one such hunt is grippingly documented on NATURE. In addition to killing for food, Goodall also found that some female chimps also kill the young of other females in their own troops in an effort to maintain dominance.

But aggression is only part of chimp life. Goodall has also documented affectionate touching instantly recognizable to people: hugs, kisses, pats on the back, even tickles. “They show gestures that we’re so familiar with,” Goodall noted in a recent speech to the National Press Club in Washington, DC.

These caresses are evidence, she said, of “the close, supportive, affectionate bonds that develop between family members and other individuals within a community, which can persist throughout a life span of more than 50 years.”

Goodall’s research “has far-reaching implications that have revolutionized the fields of observation biology and conservation,” says Dr. Robert Sullivan, who chairs the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, a $150,000 award that Goodall and two other primate researchers shared in 1997. In particular, say scientists, Goodall’s practice of following individual chimps for decades has yielded an unprecedented wealth of information for current researchers.

In 1997, for instance, University of Minnesota researchers Anne Pusey and Jennifer Williams used 25 years’ worth of data from Goodall’s project to show, for the first time, that higher-ranking female chimpanzees do indeed produce more offspring than their lower-ranking troopmates.

The researchers were able to confirm this long-debated idea only because Goodall’s project has consistently documented the reproductive success of specific females, including groundbreaking work on their use of “pant-grunts,” chimp sounds that indicate rank. Apparently, higher-ranking chimps get better access to food, and that translates into increased survival rates for their young.

Goodall’s Gombe data have also led researchers to take a closer look at the role that hunting plays in chimp feeding habits. One recent Gombe study, for instance, concluded that the 45 members of one troop ate a ton of monkey meat per year. During one hunting binge, chimps killed 71 colobus monkeys in 68 days; one chimp alone killed 42 monkeys over five years. All told, chimps may kill and eat a third of the Gombe’s colobus population each year. Researchers have also found that lower-ranking males often trade the meat for mating privileges; such trades may help prevent inbreeding by keeping a single group of males from fathering the majority of a troop’s children.

Goodall’s Gombe data have also led researchers to take a closer look at the role that hunting plays in chimp feeding habits. One recent Gombe study, for instance, concluded that the 45 members of one troop ate a ton of monkey meat per year. During one hunting binge, chimps killed 71 colobus monkeys in 68 days; one chimp alone killed 42 monkeys over five years. All told, chimps may kill and eat a third of the Gombe’s colobus population each year. Researchers have also found that lower-ranking males often trade the meat for mating privileges; such trades may help prevent inbreeding by keeping a single group of males from fathering the majority of a troop’s children.

Goodall’s legacy has especially inspired women, like Minnesota’s Pusey and Williams, to become biologists. She lectures relentlessly in an effort to get young girls and boys involved in understanding and protecting chimps and other wild animals. “If children get education, they are more likely to spread the word about conservation,” Goodall says.