Deep in the Guatemalan jungle, there’s an organization whose staff works around the clock to try to save and care for injured, orphaned and endangered animals brought to its facility from all over the country. This rescue center, known as ARCAS, is at full capacity with over seven hundred boarders of all shapes and sizes, chiefly victims of the illegal pet trade. However, the team still tries to accommodate additional rescued animals arriving daily.

The program centers on the work and challenges faced by jungle veterinarian Alejandro Morales, his zoologist girlfriend Anna Bryant, and their group of dedicated staff and volunteers, as they try to rehabilitate and prepare all types of wildlife for a return to the wild.

Filmmakers spent a year documenting the work being done at Guatemala’s busiest rescue center so they could follow the challenges faced by the staff, such as Anna Bryant’s efforts to make sure a troop of spider monkeys would finally be ready to go back to the wild after several years of rehabilitation. Her observations indicate that an adult male, called Bruce, still needs to learn to socialize more with his troop and spend more time up in the trees where it is safer if he has any hope of surviving in the jungle.

Bryant, who cares for all of the young orphaned animals at ARCAS, is also seen bottle-feeding a new arrival, a month-old spider monkey, whose mother was killed trying to protect her baby. Bryant explains how she has to strike a balance to form just enough of a bond to care for these babies, and yet not to be a constant presence hindering the rehab process. After three months in quarantine, the baby orphan will join other rescued spider monkeys to form their own troop and begin the five-year process of preparing for a return to the wild.

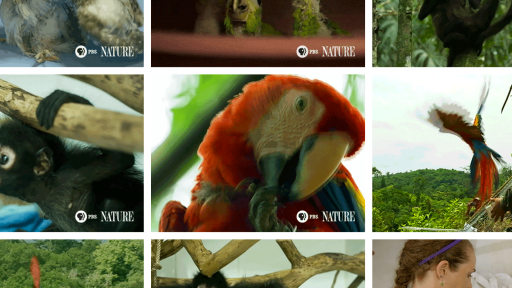

As a veterinarian treating such a variety of wild animals at the rescue center, Alejandro Morales is used to improvising when necessary. The film shows him anesthetizing a rare bird, a baby northern potoo, with a makeshift gas mask in order to operate on its broken leg. It is the first potoo ever sent to ARCAS. Although the surgery went well, attempts to figure out what food it likes did not and Morales worries the potoo can’t heal if it won’t eat. The vets also work with authorities at checkpoints on roads leading out of the jungle to locate newly-hatched baby parrots being smuggled out on buses. During the breeding season, more than a hundred baby parrots a month arrive at the center and Morales believes most can be returned to the jungle in two years as long as the team can rehydrate and feed them.

The program also documents the first time that captive-bred scarlet macaws are released into the wild in Guatemala. This history-making event marked the culmination of the center’s first captive-breeding program, led by ARCAS Director Fernando Martinez, to increase the scarlet macaw population. There are plans to release 40 more over the next five years.

Meanwhile, work never stops for the rescue center team as they continue to rehabilitate more monkeys, jaguars, armadillos, crocs and gray foxes for release; to receive new arrivals in need of care; and to track those spider monkeys and scarlet macaws, fitted with satellite collars, to determine if they are succeeding in the wild.