If Gordon Buchanan ever writes an autobiography, the Scottish filmmaker behind NATURE’s Leopards of Yala could title it “From Dishpan Hands to Distant Lands.” As a teenager on the rural island of Mull, Buchanan took a job in an eatery owned by a woman whose husband, Nick Gordon, was a wildlife filmmaker. “I’d be scrubbing pots and pans and I’d answer the phone — he’d be calling in from these exotic locations in deepest Africa,” he recalls. “It made quite an impression.” Soon, Buchanan was accompanying Gordon to West Africa on a lengthy assignment — and the beginning of a career in the field.

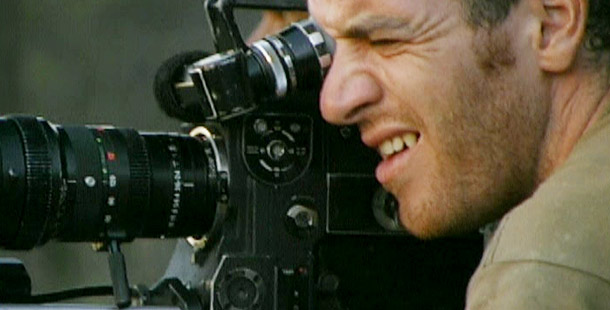

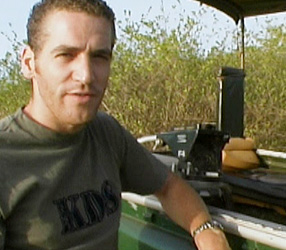

Today, the 31-year old Buchanan is one of the field’s rising stars, filming human and animal subjects around the world, from South American jungles to Africa’s Serengeti. He’s hung from ropes and hid out in blinds to capture a shot, and filmed from moving cars and soaring aircraft. In the last few years, he’s become known for his work with big cats, capturing the secret lives of lions, tigers, and leopards — particularly at night, when the large felines are often most active and special equipment is required.

Buchanan spoke with NATURE in 2003, just days after he returned to Scotland from a lengthy sojourn in India filming tigers.

NATURE: What was that first trip to West Africa like?

Well, we left in January of 1990 and spent almost a year in Sierra Leone, then were evacuated [due to civil unrest]. We were on an uninhabited island in the middle of rainforest in the southern part of the country. But we had a chance meeting with [an aide official] in the middle of the forest, and he advised us to leave due to increasing rebel activity. We weren’t really convinced, but managed to get our short wave radio working and heard that the rebel activity was getting worse jut about 40 miles away. We left, thinking we’d be back in a couple of weeks, but I never went back. I would dearly love to, but every time [there has been an opportunity] things have always flared up.

What did you think of that experience?

Culture shock doesn’t describe what I went through. I come from a very small place — there are maybe 1,000 people in Tobermory, my town, and the entire island has 2,500. I had never really traveled. So it was quite strange to go from this island community to the middle of West Africa. It was very difficult at first. I was 17 and all my close friends were just finishing school and going to university. They had an apartment together — and I was out in the middle of nowhere in a tent.

But I had always enjoyed the outdoors, and I loved watching wildlife documentaries. I had no in-depth knowledge. Still, I just thought that it would be a great job [to make them]. I love wild places and wild animals, and would like to think that I have a creative side, and there are not many jobs where you can combine those things.

How did you come to film leopards in Sri Lanka?

I had been working in the Serengeti, using low light cameras to film lions and hyenas, and I was approached about filming leopards at night in Yala National Park. Leopards had rarely been filmed during the day, much less at night, so they wanted someone who had experience with big cats and filming at night — and someone with enough drive and enthusiasm to see the project through!

We didn’t know what to expect. There was a huge sense of anticipation because we had permission to go into the park at night. People had seen all these animal tracks in the morning, or maybe a kill had disappeared over night. So we assumed there was a lot of night activity. But initially, it was huge disappointment; there was much less activity than we expected. The reality was that it was as hard to find leopards during the night as it was during the day.

Out of maybe 200 days filming, we spent at least 150 days in the park until 11pm — and got relatively little footage. I would wake at 4:30am to prepare my equipment and try to wake up enough to be in top leopard-spotting mode. I’d grab a couple of hours sleep in the hottest part of the day, when leopards are doing likewise. If nothing was happening, I would go back to my room to write up notes, clean the gear, and would go to bed normally before midnight for another four hours sleep, and repeat the same routine day after day.

If there was something happening, such as a kill, we would stay in the park pretty much round-the-clock, breaking only for food and sleep. [In retrospect], there was a bit of wasted effort. If I were to do it again, I would conserve my energy for those nights when there was definitely a chance of something happening. Any tiredness during the day meant that you wouldn’t be as vigilant when spotting leopards.

Leopards can be hard to spot.

You have to be alert all the time. You couldn’t switch off and hope one was going to run across the road. Leopards can be anywhere — in the top of the tree, behind the tree, at the bottom of the tree. Just anywhere. So there isn’t one square inch of an area that isn’t worth scanning to try and spot a leopard — it, above and beyond any of the big cats, is a master of disguise.

What will you remember most about filming in Yala?

The highlight certainly was the night filming the leopard kill when the sloth bear came along. I’ll put that in my top three close shaves. It wasn’t a moment of real panic but I was certainly worried. When the leopard cleared off and the bears showed up, all there was between me and them was a flimsy piece of canvas. I’d been in there all day with some food, and they came over and tried to get in. I was glad I decided to clear out.