It was an epic confrontation: a small slender shepherd named David facing off against a towering burly warrior named Goliath. The end of the contest is well known: it was an upset for the ages. The underdog David slew the favorite Goliath on the sands of the ancient desert of Judea.

But what is often overlooked is that David fled after his surprise victory. According to the Bible, he slipped into the cool crags of Ein Gedi, a moist oasis on the western shore of the Dead Sea. And as NATURE’s Lost World of the Holy Land shows, today Ein Gedi is still a refuge, this time for some of the region’s threatened wildlife.

Ein Gedi, a network of craggy limestone cliffs and deep chasms, is brought to life by water. Four springs bubble forth here, together sloshing about 3 million cubic meters of water a year across the rocks. It is a welcoming pool of green in an otherwise hot, dry desert.

Not surprisingly, the region’s earliest human settlers sought out the refuge, building encampments near the springs. By the fourth century, archeologists say Ein Gedi was a thriving community. Farmers tilled the land and built an extensive network of terraces, aqueducts, and reservoirs. Much of their wealth may have come from raising balsam, a fruit used to make a valuable perfume. Diggers have found the remains of palatial homes and extensive storehouses — all signs of prosperity that reigned for several hundred years.

Slowly, however, Ein Gedi’s prosperous community began to decay. By the 19th century, the region was considered a wild land populated by just a few nomadic families. After the creation of Israel in 1947, highly organized agriculture returned, and today a small community — about 500 people — lives in the area. But Ein Gedi is pehaps better known as a wildlife sanctuary.

In 1972, the government created a 7,000-acre reserve that is home to an array of plants of animals — including the horned Nubian ibex, the animal that probably gave the area its Biblical name: “Crags of the Wild Goats.”

As Lost World of the Holy Land shows, ibex display fascinating behavior. Males and females typically live in separate herds. But when the fall mating season arrives, there are ferocious courtship battles among the males. And come spring, mother ibex can be seen shepherding their newborn kids down from the desert to the springs.

Another intriguing resident is the hyrax — a small rodent-like animal that is actually a close relative of the elephant. And there are predators as well, from two kinds of foxes to the shy striped hyena and the endangered leopard.

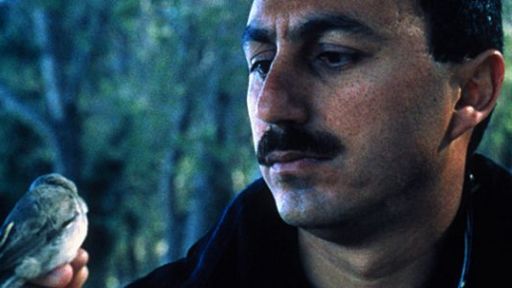

Ein Gedi’s skies are also alive. During migration season, thousands of hawks and storks soar over the reserve. Other species, from brash songbirds to watchful quail, are full-time residents. Some have earned their own mentions in the Bible, such as a “dove, in the cranny of the rocks, hidden by the cliff.”

Today, like David long ago, some of these animals are the underdog in the struggle for survival. But reserves like Ein Gedi offer hope that they too will overcome the odds and prevail.