Modern Zoos

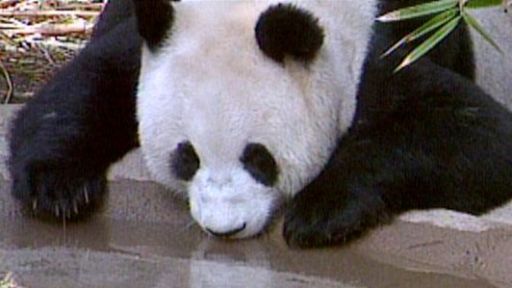

It’s not Australia, but koalas feel at home. If you are the sort of person who complains about overly large zoo exhibits that allow animals to stray from the most prominent viewing areas, you should take a closer look at what these wildlife parks are trying to accomplish. As “Gorilla Tropics,” “Polar Bear Plunge,” and other San Diego Zoo areas demonstrate in Animal Attractions, the zoo is not a “living museum,” but a place where animals should feel at home. Today, zoos combine educational exhibit areas with backstage research areas where zoologists study the animals under their care.

Visitors are captivated by animals at the zoo. During the latter part of the 20th century, zoos began to provide a new experience for visitors by replacing the iron bars and concrete walls of cages with protective moats, bigger animal areas, and recreated tropical rainforests. The San Diego Zoo, founded in 1916, helped pioneer this shift.

Zoos used to keep all animals in cages. In 1868, Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo was reportedly the first zoo in the United States to open its gates to the public, followed closely by the Philadelphia Zoo and New York’s Central Park Zoo. These parks filled their cages with wild-caught animals. As the burgeoning populations and growing industries of the 20th century began decimating wild habitats, zoos took on the role of housing remnants of once-thriving animal populations.

Zoos used to keep all animals in cages. In 1868, Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo was reportedly the first zoo in the United States to open its gates to the public, followed closely by the Philadelphia Zoo and New York’s Central Park Zoo. These parks filled their cages with wild-caught animals. As the burgeoning populations and growing industries of the 20th century began decimating wild habitats, zoos took on the role of housing remnants of once-thriving animal populations.

Then in 1907, Carl Hagenbeck, of the Tierpark in Hamburg, Germany, thought of using moats rather than bars to enclose animals, but this trend took more than a few years to catch on. Dr. Harry Wegeforth, founder of the San Diego Zoo, was determined to create moated exhibits, and in 1922, the first lion area opened, free of any enclosing wires. At first, visitors were afraid that the lions would escape and attack them.

Today, a walk through the Bronx Zoo’s “Wild African Plains” exhibit shows how this technique offers the public a seamless view of animals coexisting, as if side by side in the wild. The African antelope and its predator, the lion, appear to be in the same field, when in fact they are separated by a deep, wide gully. This type of gap deters the lions from hunting the antelope — not to mention hunting the visiting humans

An even better simulation of the safari experience takes place at the San Diego Wild Animal Park. Here, photo caravans transport tourists through a pasture of giraffes, zebra, ostriches, rhinos, and many other species visitors might have had to travel to Africa or Asia to see in the wild. But unlike a real safari, here visitors may safely feed the animals, which have been tamed through repeated human interaction and, in fact, seem to look forward to visits. This 2,200-acre park is home to more than 2,500 animals.

But since that kind of acreage is oftentimes not available, architects struggle to make exhibit areas spacious and interesting to their inhabitants and visitors. Since the 1960s, zoo horticulturists have built naturalistic habitats that reach new levels of creativity. A big issue is that of “psychological space” — the idea that the animal should feel that it is actually in the wild. Examine the case of the San Diego Zoo’s “Polar Bear Plunge,” featured in the NATURE program, which took two years and seven million dollars to build.

There is no way a zoo near a major city can approximate the vast distances of the Arctic. So, instead, the zoo architects who designed “Polar Bear Plunge” tried to give the bears a stimulating, varied environment that would prevent them from becoming bored. Zoo keepers provide toys and puzzles (such as fish stuffed into a column of ice for the bears to dig out), slides, pools, and streams, all in an effort to make the polar bears feel at home.

But designers must also keep the safety of the public in mind. Polar bears are, after all, powerful, 10-foot-tall wild animals capable of causing serious harm to people. The zoo walled the bears behind solid concrete and constructed a thick glass barrier, so visitors could watch the bears underwater and feel that they were getting as close to them as possible. Interestingly, they found out that the bears seem to be as fascinated by the public as the public is by them.

According to Fred Beiner, president of the Association of Zoological Horticulture, designers must tackle issues of insect control, drainage, plant toxicity, and durability, and also must depict the animal’s natural habitat accurately and provide it with an interesting environment. Most importantly, he states, a good zoo exhibit should combine these elements with a clear view of the animals for the public and educational signs that describe what they see.