Native to North America , the common turkey was tamed between 800 BC and 200 BC by the people of pre-Columbian Mexico. However, these early Americans weren’t the only ones to breed the bird.

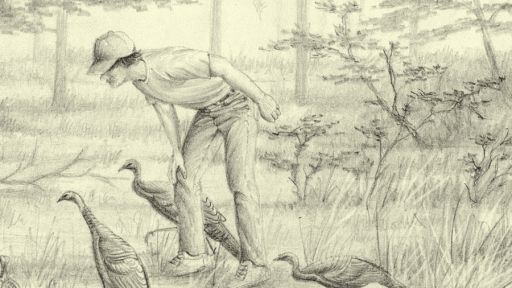

Scientists conducting DNA analysis of ancient turkey remains recently discovered that the Pueblo peoples of what is now the southwestern United States achieved their own distinct domestication around 200 BC. For more than a millennium, Pueblo turkeys were raised primarily for their feathers, which were used in rituals, ceremonies, and textiles; it wasn’t until around 1100 AD that the turkey became an important source of sustenance for the Puebloans.

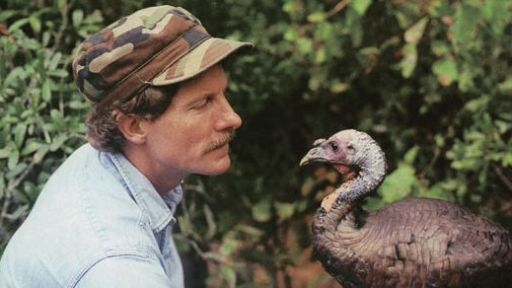

Despite centuries of successful breeding, some researchers believe that the Pueblo turkey may have become extinct, but no one knows for sure. DNA tests indicate that it is most closely related to two modern subspecies of wild turkey, the Eastern and Rio Grande, which roam U.S. forests and fields to this day. What is clear, however, is that the Pueblo breed did not become part of the modern domestic turkey’s bloodline. Instead, the distinction of “closest cousin” goes to the Aztec turkey, a direct descendent of the breed that was first domesticated in pre-Columbian Mexico.

When Spanish conquistadors encountered Aztec turkeys in the early sixteenth century, they promptly shipped the bird back to Europe. Here, esteem for the Aztec turkey rose with remarkable speed – no small feat, as New World fare was often embraced rather tentatively in the Old World. According to food historian Andrew F. Smith, there are number of factors that likely contributed to the turkey’s surprising popularity: it tasted good, it reproduced quickly, it was easy to care for, and it was relatively inexpensive to produce.

When Spanish conquistadors encountered Aztec turkeys in the early sixteenth century, they promptly shipped the bird back to Europe. Here, esteem for the Aztec turkey rose with remarkable speed – no small feat, as New World fare was often embraced rather tentatively in the Old World. According to food historian Andrew F. Smith, there are number of factors that likely contributed to the turkey’s surprising popularity: it tasted good, it reproduced quickly, it was easy to care for, and it was relatively inexpensive to produce.

By the mid-sixteenth century, turkeys were common throughout Europe. When the first English colonists set off for what is now the eastern United States, they brought their turkeys with them – and so the bird crossed the Atlantic once again.

Fortunately for the colonial turkeys, the wild breeds encountered in North America were plentiful and large – significantly larger than the domestic birds shipped in from Europe. Settlers focused their attention on hunting rather than breeding until the supply of wild turkey was all but exhausted, at which point they began incorporating untamed birds into their domestic stock. This experiment produced the predecessors of the large-breasted domestic turkeys we are familiar with today, including the modern Thanksgiving turkey.

And which breed (wild or domestic) was served at the first Thanksgiving? The answer, most likely, is neither. Instead, the menu seems to have featured venison, seafood, duck, and goose. Though it is unclear exactly when turkeys and Thanksgiving became so closely entwined, the one thing that is obvious is that the turkey’s place on the table has been firmly established.