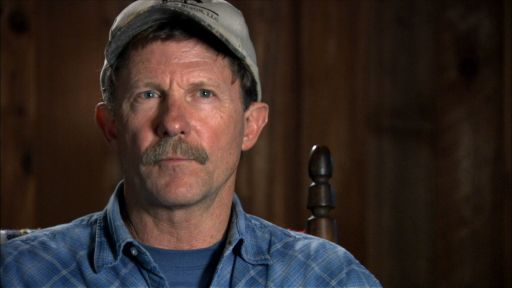

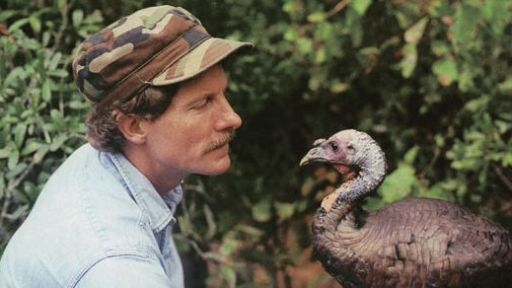

When naturalist Joe Hutto became “mother” to a flock of wild turkeys, it gave him a unique opportunity to immerse himself in their lives and see the world through their eyes. He was not a stranger intruding, but rather the heart of the flock. He was able to do this by taking advantage of a biological phenomenon known as “imprinting.”

Imprinting refers to a critical period of time early in an animal’s life when it forms attachments and develops a concept of its own identity. Birds and mammals are born with a pre-programmed drive to imprint onto their mother. Imprinting provides animals with information about who they are and determines who they will find attractive when they reach adulthood.

Imprinting has been used by mankind for centuries in domesticating animals and poultry. In Rome, in the first century B.C., agriculturalist Lucius Moderatus Columella wrote a treatise on agrarian practices and suggested that “anyone wishing to establish a place for rearing ducks should collect wildfowl eggs in the marches and set them under farmyard hens, for when they are reared in this way they lay aside their wild nature.” For centuries in rural China, rice farmers have imprinted newly hatched ducklings to a special stick, which they then use to bring the ducks out to their rice paddies to control the snail population.

But, it was not until the early 1900s that any scientific studies were done of the phenomenon. Austrian naturalist Konrad Lorenz became the first to codify and establish the science behind the imprinting process.

Lorenz found that when young birds came out of their eggs they would become attached to the first moving object they encountered. In most cases in the wild, that would be their mother. But Lorenz replaced himself as the object of their affection. And it wasn’t just him that the young birds would attach to as a mother substitute. They would just as easily attach to inanimate objects and oddities, such as a pair of gumboots, a white ball and even an electric train – if it was presented at the right time. The hatchlings have been prepared by natural selection to form an immediate strong social bond.

Lorenz’s work with geese and ducks provided concrete evidence that there are critical sensitive periods in life where certain types of learning can take place. And, once that learning is ‘fixed,’ it is the least likely to be forgotten or unlearned. Lorenz’s geese responded to him as a parent, following him about everywhere, and when they became adults, courted him in preference to other geese.

Researchers building on Lorenz’s work have identified other such unique windows of opportunity for both animals and people to acquire knowledge. For birds like ducks, geese and turkeys, that hatch and begin walking around, the need to follow something for their own safety is vital to their early survival, so imprinting happens in the first few hours and days.

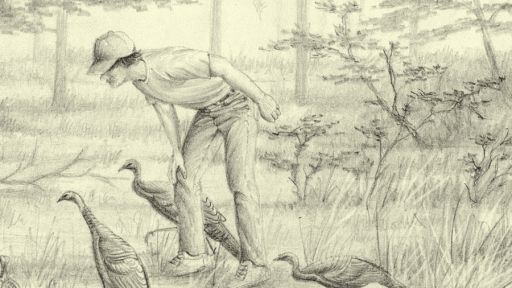

Joe Hutto used this sensitive time period to become the parent to his flock. When the poults are born, the first thing they do is look about for a parent to bond to. They are attracted to movement, sound and smell. Joe used all three of these to reinforce the poults attachment to him as their mother. While they were incubating, he spoke to them, in both “turkey” and English, to get them used to the sound of his voice. When the poults hatched, he was positioned to be the first thing they would see. When the first poult emerged, he made his turkey sound and, as Joe recounts, the poult turned its head, its eyes met Joe’s and “something very unambiguous happened in that moment.” A connection had been made.

The new hatchling made his way over to Joe and huddled up against his face. Over the next few hours this was repeated with all the baby birds. And, the attachment was reinforced as he spent 24/7 tending them as a parent would. They came to associate the sight, sound and smell of him as their mother.

But the biological imperative that drives imprinting can have its negative side. Conservationists and naturalists have become sensitive to the damage imprinting can cause in young animals who attach to people or objects instead of a parent. Birds that imprint on human ‘parents’ prefer their company to that of their own species. They are unlikely to ever return to the wild or socialize appropriately with their own kind.

This has led to the development of some novel approaches in captive breeding programs. In California and Arizona, at the Condor Recovery Project, eggs are incubated and the chicks are raised by caretakers using a hand puppet shaped like a condor head; while researchers at China’s Wolong Panda reserve take it a step further – dressing in full, furry panda suits whenever they have to interact with the animals, believing that the cubs must live devoid of all human contact if they are to have any chance of survival.

But the implications for imprinting extend far beyond geese and pandas. Researchers since Lorenz’s time have found that imprinting is a component in all animal and human interaction, and can be a more plastic and forgiving mechanism than was originally thought. It plays a role in determining who we love and who we live with – not just how a man can become mama to a turkey.

Photo © David Allen