Walk into the Monterey Bay Aquarium and you may find yourself surrounded by a ghostly swarm of luminous, pulsing phantoms. The specters are actually moon jellies — common marine creatures — swimming in darkened, mirrored tanks that give visitors the illusion of strolling through a shadowy ocean. “It’s a marvelous feeling — people love it,” says aquarium biologist Dr. Randy Kochevar, who appears in this week’s NATURE: Oceans in Glass: Behind the Scenes of the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Moon jellies, however, are just one species in the aquarium’s dazzling collection of jellyfish — boneless, gelatinous creatures that may be warning us of trouble in the sea.

Jellies live in virtually every part of the ocean and come in a dizzying array of shapes, sizes, and colors. Some, like the aquarium’s box jellies, are no bigger than a thimble. Others, like the Arctic lion’s mane, have umbrella-shaped bells that reach 7 feet across and tentacles that stretch 100 feet or more. Jellies often use their tentacles to sting and snare prey, such as small fish, while drifting with the current. The flower hat jelly, another species on display in Monterey, has even grown a colorful tentacle fringe to help it lure in prey.

Not all jellies rely on their tentacles for food. Some have joined forces with specialized microorganisms that live beneath their bells. These cooperative jellies simply turn upside down and rest on the bottom of shallow seas, letting their guests soak up the rays and produce food. In tropical waters, it’s not uncommon to see thousands of these inverted, sun-loving jellies on the sea floor, creating a scene that looks a bit like a marine flower garden.

In some waters, however, an explosion in jelly populations, or blooms, has scientists worried. They say more jellies may ultimately be a sign of fewer fish — and a less healthy ocean.

One of the first warnings came more than 20 years ago, when researchers studying the Black Sea, which straddles Eastern Europe and Asia, began to notice huge numbers of a jellyfish named Aurelia aurita. They suspected these massive blooms were due to increasing pollution and massive irrigation projects that reduced the amount of fresh water flowing into the Black Sea, making it saltier.

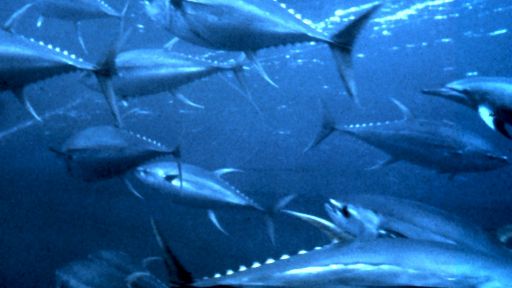

Soon, the scientists found that the jellies were eating up to two thirds of the sea’s zooplankton (microscopic animals), which meant they were competing directly for food with several kinds of commercially important fish, including anchovies. A number of researchers believed this competition was one reason anchovy stocks had begun to dwindle.

Some help arrived in the late 1980s, when engineers increased the amount of fresh water flowing into the Black Sea, making conditions less favorable for the jellies. But the story wasn’t over. Cargo ships apparently carried another kind of jelly — a species typically found in the Atlantic — into the Black Sea, where it also began blooming in huge numbers. Ultimately, the two species began to alternate, with one numerous in some years and the second swarming in others.

As a result, “nearly all of the zooplankton production in the Black Sea appears to have gone from feeding fishes to feeding jellyfish,” concludes marine biologist Claudia Mills of the University of Washington, a leading expert on the organisms. She also believes that the jellyfish may be one reason anchovy populations remain low.

Mills and other scientists have also documented unusual jelly blooms closer to home, in the waters off Alaska and New England. In recent years, the Gulf of Mexico has also been plagued by invasions of a spotted jelly native to the Caribbean. Few people have ever seen them in such numbers — swarms so big that Gulf states have been forced to shut down parts of a shrimp fishery worth tens of millions of dollars.

The jellies are so thick that “the weight stops even a 90-foot boat cold,” one shrimper told the magazine One Earth. “It’s like crashing into a brick wall. You can’t go forward. You can’t back up, because the nets get tangled in propellers. And the nets are too heavy with jellyfish to even pull them up.” Some scientists even joke that, the way things are going, people will need to start eating jellies instead of fish or shrimp.

On a more serious note, researchers contend that the causes of jelly blooms are often mysterious, although overfishing, pollution, and climate cycles are probably playing a role. In part, the mystery is due to a lack of understanding of basic jellyfish biology. Scientists don’t know exactly how many species live, breed, and survive. At the Monterey aquarium, researchers are solving some of these riddles by raising jellies for display in a specialized “jelly farm.” The tanks allow scientists to fiddle with everything from water temperatures to food supplies to find the perfect conditions the creatures need to thrive. Eventually, they say, such studies could reveal what these ghostly, pulsing organisms are telling us about the health of the ocean.