In the early dawn of March 31, 2005, researchers from the Monterey Bay Aquarium made history. Standing on a small boat far off the coast of California, they carefully lifted a sling carrying a six-foot-long great white shark over the side and — splash! — the powerful fish was back in the wild, after spending a record 198 days at the aquarium.

As NATURE’s Oceans in Glass shows, displaying a great white — one of the sea’s most impressive predators — has long been a dream of aquariums around the world. But previous efforts to care for the sharks — which can grow to weigh two tons and measure 21 feet long — have largely ended in failure. The great whites proved too big, too aggressive, or too sensitive to live penned up. Some wouldn’t eat, says biologist Dr. Randy Kochevar of the aquarium, “and sharks can’t survive long if they aren’t feeding.”

In Monterey, however, biologists working on the aquarium’s shark conservation and ecology project believed it was possible for a great white to survive — and thrive — in one of the facility’s giant display tanks. They also believed that letting the public see these magnificent hunters up close could pay big dividends for their efforts to protect sharks, which are under increasing threat.

With this goal in mind, several years ago the aquarium’s researchers began experimenting with ways to keep a captive shark happy. First, they built an enormous 4-million-gallon pen in the ocean off Malibu, California. When commercial fishing boats accidentally caught a great white, the aquarium arranged for it and several others to be moved to the pen. There, researchers learned to feed the sharks and understand how they behaved in captivity.

Those lessons bore fruit in August 2004, when a commercial halibut fisherman caught a young, five-foot long female great white in the waters off Huntington Beach. After being held in the Malibu pen for three weeks, she was moved to the aquarium for display. Over the next six months, nearly one million people came to see her. “She was an incredible ambassador for white sharks and shark conservation,” says Kochevar.

But the young shark was also growing bigger and more restless. “She basically grew more than a foot and gained 100 pounds,” according to Kochevar. “And one day she apparently decided she needed to increase the breadth of her diet,” which consisted mostly of salmon and other fish fed to her by aquarium staff. The great white began stalking other animals in the tank, eventually attacking two smaller soupfin sharks. The staff decided it was time to release the growing animal back into the wild, but not before she provided one last service to science.

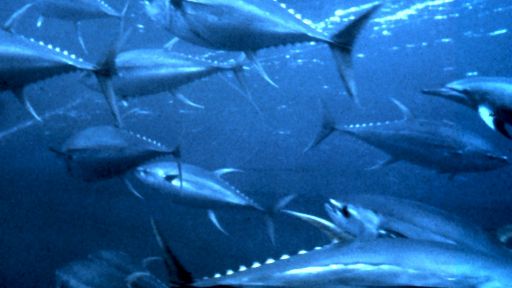

On their way to the release site, researchers attached a sophisticated electronic tag to the shark that would record her movements for 30 days and then pop off, transmitting its location to a satellite for retrieval. Similar tags have helped revolutionize our understanding of the habits of a myriad of animals, from sharks and sea turtles to seals and bluefin tuna. Indeed, the aquarium is part of an innovative effort — called the Tagging of Pacific Pelagics (TOPP) project — that is harnessing all kinds of marine animals to carry sensors into the ocean.

In the great white’s case, the tag worked perfectly. After popping off the shark on schedule, the tag was retrieved from surly seas off the coast of Santa Barbara by Stanford University doctoral student Kevin Weng. “They lose container ships out there!” he exclaimed after using a long-handled net to scoop the tag out of the whitecaps.

The researchers say the tag showed that after being released, the shark swam more than 100 miles offshore and to depths of greater than 800 feet. “It’s clear she survived and thrived,” says Kochevar, adding that the shark first swam several hundred miles south along the California coast, “then took a hard right and headed offshore for a while, then returned to the coast. … There’s no question that she was hunting and feeding on her own.”

Similar data from other young sharks is beginning to give scientists a picture of how these animals use the ocean and how people could improve conservation efforts, according to Kochevar. There is little question that the great white’s brief stay at the Monterey Bay Aquarium has helped stoke public support for shark research and conservation, he adds. Not long ago, the aquarium’s trustees decided to increase their shark research budget by half a million dollars.

To learn more about the TOPP project, visit http://topp.org/.