Christian Cooper:

I was actually dealing with the fallout about National Audubon not changing the name. And my sister happened to text me about something completely unrelated, and she didn’t know about the Audubon controversy. I texted back to my sister, and I put it in pretty non-partisan terms. I’m like, “Well, Audubon was a slave owner and a racist. So some people think that it might be time to lose his name from the organization, but National just announced that they decided that they were going to keep the name.” And my sister texted back that, “(beep) that.” And I’m like, “Okay. So this is what we’re dealing with.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

I am Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant, and this is a different kind of nature show, a podcast all about the human drama of saving animals. This season, we’re going to take a journey through the ecological web, from the tiniest of life forms to apex predators. We’ll hear stories from scientists, activists, and adventurers, as they find all the different ways the natural world is interconnected. And together, we’ll explore our place in nature. This is Going Wild.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

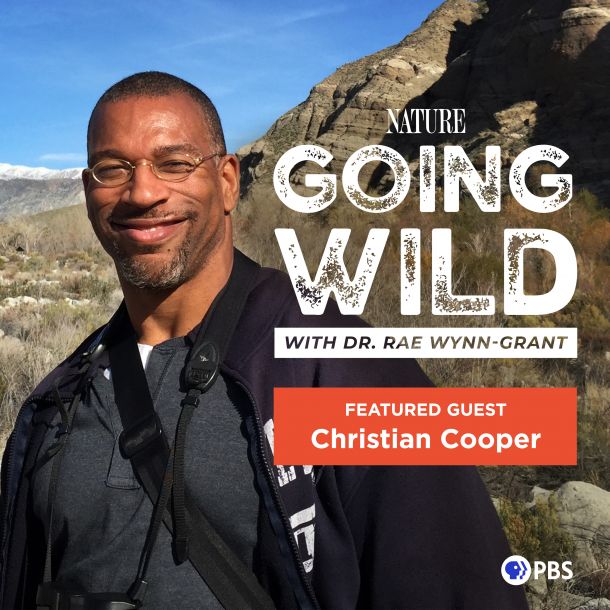

Christian Cooper is a birder, conservationist, writer, and nature show host. And even if you’re not a big birder, you’ve probably heard of Christian.

Woman in Park:

And there is a man, African-American, who has a bicycle helmet. He’s recording me and threatening me and my dog.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Back in 2020, at the height of the pandemic, he recorded a video of a white woman, threatening to call the cops on him at Central Park, after he asked her to put her dog on a leash.

Christian Cooper:

Please, don’t come close to me.

Woman in Park:

Sir, I’m asking you to stop recording me.

Christian Cooper:

Please, don’t come close to me.

Woman in Park:

Let me take your photo.

Christian Cooper:

Please, don’t come close to me.

Woman in Park:

And I’m taking pictures and calling the cops.

Christian Cooper:

Please, call the cops. Please, call the cops.

Woman in Park:

I’m going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.

Christian Cooper:

Please tell them whatever you like.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

His sister tweeted that video, and it went viral. It was all over the news and overnight, Christian became famous. The newfound fame has certainly changed Christian’s life, but one thing that hasn’t changed before or since the infamous Central Park incident is the fact that Christian knows how to keep his cool during a heated controversy. And when I talked to him recently, he was dealing with a new controversy, this time, surrounding the Audubon Society, an environmental organization dedicated to bird conservation. The Audubon Society is named after the naturalist and ornithologist, John James Audubon, who famously created detailed illustrations of American birds in their natural habitats. His book, the Birds of America, was originally published in 1827 and really put North American birds on the conservation map.

Christian Cooper:

So why do we care about the name “Audubon?” Well, it’s become sort of synonymous with North American birds and birding. But in recent years, Audubon’s history with racism, with slave owning, with desecrating Indigenous graves, all of that has come to light. And so, that’s raised a lot of questions as to whether or not you continue to use the name “Audubon.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

The National Audubon Society’s Board of Directors debated this issue for a year. And then, in March, 2023, after that year long conversation, the board voted against changing the name.

Christian Cooper:

They decided that the name Audubon transcended the man and his flaws and that they were going to keep the name.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And honestly, I wish I could say that I was as neutral as Christian was when he was explaining this to his sister, because when I found out about this, I kind of had the same reaction his sister did.

Christian Cooper:

“(Beep) that.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But Christian reacts to things differently.

Christian Cooper:

I have a very Vulcan mindset.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So for those of you who aren’t Star Trek fans, Vulcans are those guys with the pointy ears. Like if you’ve ever heard of Mr. Spock, well, he’s a Vulcan. Anyway, the Vulcans are known for being these super rational beings. As someone with a Vulcan mindset, instead of getting caught up in the emotional reactions, Christian tries to parse things out logically. Following the news that National Audobon isn’t going to change its name, a handful of local chapters of the organization have dissented, and they are determined to change their names.

Christian Cooper:

Especially urban Audubon chapters, and that includes Seattle Audubon, Portland Audubon, Madison, DC Audubon, and then, I’m a board member of New York City Audubon, full disclosure. So in our laps, we too had to make this decision.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And for me, the answer is super obvious. Yeah, get rid of that name. If you can show up as an ally and fight racism by changing this one thing, why not just do it? But for Christian, this is actually a pretty fraught issue.

Christian Cooper:

I really was divided on the issue, because as a Black man, I’m repulsed at what he did. And then, there was the other half of me, who’s been a birder since I was a little kid, who has grown up with Audubon being nothing but birds and birding. That’s what it means, nothing else. And that part of me is like you can’t abandon that name, that’s invested with all kinds of things for all kinds of people, that are only about birds and birding. So here are my two halves. How am I going to vote when this comes up for New York City Audubon?

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And this decision is such a big deal to Christian, because back when he was just a kid, the Audubon meant a lot to him.

Christian Cooper:

My dad was a science teacher, a biology teacher. So nature was always big in our household. We ended up taking a cross-country camping trip. Me, my mom, my dad, my sister, and the family cocker spaniel all poured into a little Volkswagen Westfalia Camper, one of those little van things. So there wasn’t much room for stuff, but one of the things my dad made sure to bring was a field guide to the birds. And that was exciting, because it had the pictures of the birds right opposite their description. And it had all the birds in North America, not just the eastern birds, but the western birds too. So you’re spending hours driving across the country. There’s not much going on.

You’re watching farm fields pass by for hours. So I would flip through the book, and at the time, I had a decent memory and not much else as a kid that had occupied the brain space. And by the time we reached the west coast, I would see this bird fly by, and I’d go, “Oh, look, mom and dad. There goes a black-billed magpie.” And they’re looking at me, and they’re like, “How the hell does he know that?” I’m like I remembered the book. So that was sort of the basis of my interest in birds, and it just kind of grew from there.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And the person Christian can thank for nurturing these initial sparks is his father.

Christian Cooper:

My relationship with my father was very complicated. He could be very difficult and remote, but at the same time, as a school teacher, he works very hard five days a week. Weekends were his time off. Yet he would get up at the crack of dawn on Sunday mornings, his day off, so that he could take me out to the bird walks of the South Shore Audubon Society. And that was huge. That was for me.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Because not only did Christian’s father spark his interest in birds by giving him that field guide, but he also introduced him to the Audubon Society, an organization full of people who are just as obsessed with birds as he was. The first Audubon walk his father took him to was at the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in Queens, New York.

Christian Cooper:

That was absolutely my first time being in a group of other birders, and one birder in particular, I would be remiss if I didn’t highlight his influence and his presence there on that first walk-in. And that’s Elliot Kutner. He saw this little kid coming on the walk, all white people, except for my little brown face and my dad. And he saw a bird. I think he took a quick look, and he said, “Oh, okay, there’s a woodcock over there.” And I’m like, “Oh, a woodcock. I’ve never seen a woodcock.” And I’m looking through the scope. It’s far away, but I could see enough of it, probably because I had very young good eyes back then.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And what Christian saw through his binoculars was this pudgy bird with short, stocky legs and brown stripes across its head.

Christian Cooper:

And I’m like, I said to my dad, “I don’t think that’s a woodcock. I think that’s a snipe, because of the stripes on the head.” And my dad said, “Well, go tell Elliot,” because Elliot was the leader of the walk. And I’m like, “Oh my God, here comes a humiliation factor from beyond.” But I go up to Elliot and I’m like, “I think that’s a snipe, not a woodcock.” And he looked at me and he stared at me. And he looked in the scope, and then, he said, “You are right. Those are snipe. Everybody, these are snipes.” And he just beamed. And after that, he was like, he took me under his wing, and he was my birding godfather for my youth.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And I can speak from my personal experience that having a mentor who sees your potential is truly life-changing. When I was in grad school, I had a mentor who really fought for me to be accepted into the PhD program, and she held my hand through my early career as a scientist. And as a young Black scientist like me, who had just started in a field that was so white, knowing that someone had my back, it made a huge impact. And it was the same for Christian too.

Christian Cooper:

There was no doubt that Elliot embraced me full on, and he took one look at my interest in birds and he made it his business to nurture that interest.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Elliot gave Christian birding tips that were super useful for a newbie.

Christian Cooper:

One thing I remember vividly is, Elliot talked about how he had taken a garbage can lid and dug a trench in his backyard, and then, he had hooked up a garden hose above the lid and let it drip into the lid, so that water spilling over from the lid into the trench, it created a little stream. And that sound of the dripping water would bring in the birds, including the migrant birds that wouldn’t come to a feeder, because they don’t eat seeds. They eat insects. But they all want to bathe and drink and refresh themselves, particularly when they’re migrating. I was like, “Elliot, that’s brilliant.” So here I am, this little kid, and I get a garbage can lid. And I go in the backyard, I dig a trench, and I hook up a hose and let it make my own little mini Mississippi down in the backyard. And I would spend hours sitting on a stool at my window, which overlooked my little mini Mississippi trench, and I would just wait and see what would come.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

His mini Mississippi brought all sorts of migratory birds to his backyard. But even just seeing the usual neighborhood birds became a different experience.

Christian Cooper:

The neighborhood robins would come in, and I would get a view of them and study them. I’m like, “Oh, wow, I never noticed. They have a little broken white ring around the eye, and they’ve got two white spots at the corners of their tail at the back. And all these…”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Christian was noticing all these little details that he never paid attention to before.

Christian Cooper:

That was Elliot’s gift to me was my backyard trench and the birds it brought right up close to my window.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But birds weren’t the only gift he received from Elliot. Knowing there was someone who cared and had an interest in him felt really good. And these early experiences Christian had, meeting other birders, learning from his mentor, this is what the Audubon means to Christian, even to this day. It’s not just an organization. It’s about finding that small sense of belonging, which is huge, because in many other ways, growing up, Christian felt like he was out of place.

Christian Cooper:

There are no kids in my world that went birding, and I’m a Black kid. There were no Black people in my world who go birding.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Back then, even more so than now, Black birders were rare. For the same reasons Black and brown people today don’t have equal access to nature, this was even more true when Christian was a kid, which meant there weren’t a lot of Black folks out in nature, hiking, exploring, let alone nerding out over birds. So it’s not surprising that Christian felt so out of place being the only Black birder around.

Christian Cooper:

Already being sort of like a smart Black kid, who was into science fiction and really nerdy, and now, I’m birding too. It’s like, “Okay, he’s lost. He’s lost to the world.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But it wasn’t just about being a nerd, that feeling of being lost to the world as an outsider was compounded, because Christian also knew, from a very young age, that he was gay. And back then, in the seventies and eighties, when he was growing up, being gay was truly unspeakable and sometimes even dangerous.

Christian Cooper:

When I was a kid, on the rare occasion that a gay person showed up, it was as the shorthand for decadent evil or some mentally disturbed, troubled, “Oh my God, that poor individual” character.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Even in the privacy of his own home, with his own parents, Christian knew that he needed to keep his queerness to himself. He recalled this one conversation he had with his parents. He couldn’t remember how the subject of homosexuality came up exactly, but he never forgot his parents’ reactions.

Christian Cooper:

I would say, I must have been probably about 12 or 13 when this conversation came up at the dinner table, and they said what a homosexual was. And I just remember I didn’t say anything. I knew better, somehow, and I just went into my room. And I shut the door, and I thought, “But that’s what I am.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Throughout his childhood, Christian played it straight, and he kept that secret inside of him for what felt like an eternity.

Christian Cooper:

Knowing I was queer from the age of five or something like that, the way I always describe it is I felt like I was buried alive. And that was a horrible feeling. It felt like you were suffocating every minute.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And in those moments when he felt suffocated, he took refuge in the things that he loved, comic books, science fiction, and of course, birding.

Christian Cooper:

You can be wrapped up in all your problems, and then, you step outside and you feel the breeze and you see the sky and you’re amidst these green things. Or maybe you’re in a gray swamp somewhere, but you’re seeing sort of this whole natural world, that has nothing to do with your problems. If you’re birding, you’ve got to be noticing motion out of the corner of your eye. You’ve got to be attuned to a particular kind of motion that distinguishes a falling leaf from a bird flitting from branch to branch. So as you do this, you are just drawn out in a very meditative way. It reminds you that there’s a whole world out there that is doing its business, regardless of what’s going on in your life. And for those moments that I was out in the field and paying attention to birds, I wasn’t suffocating anymore.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Those moments when he was drawn out of his misery and loneliness into his fascinations, be it birds or comic books or science fiction, they were like exercises to achieve that Vulcan mindset, where he learned to pause and distance himself from the storm of his emotions. And these little moments of refuge were what got him through the worst parts of his teenage years.

Christian Cooper:

I didn’t get to kiss a romantic partner or go on dates or anything like that, because I was in terror that somebody would find out.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

It wasn’t until he got to college that Christian finally saw the light at the end of the tunnel. Like a lot of young people who are eager to reinvent themselves when they get to college, Christian did the same. Though for him, it was less about reinventing himself, but becoming more of who he had always been. So he slowly began to come out to his peers, to his roommates, and eventually, even to his dad. One day in college, when Christian was visiting his dad, they were driving home, and right there in the car, Christian decided to bite the bullet.

Christian Cooper:

I really felt I needed to get this out of the way and let him know where things stood. So I told him, and he just kind of said, “Oh.” I was like, “That’s it?” And then, he added, “Well, do you want to see somebody about that? Do you want to see a therapist, a psychologist, whatever?” And I was like, “No, I’m good with it.” “Oh.” And that was it. That was the extent of the conversation.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And other than that one conversation, his being gay was never mentioned again between him and his dad for many years.

Christian Cooper:

He was so inscrutable to me in so many ways. His dark moods, the source of them was unknown to me. And I think I had internalized the idea that, okay, maybe he picked up on the fact that I was queer. And that is one of the reasons why he was so difficult when I was a kid. Whether that was true or not, hard to say, but because I was so unsure and our relationship was so tenuous to start with, I was like, “I’m not going to bring this up. I don’t feel like dealing with this with him.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So for a long time, Christian kept the queer part of his life away from his dad, because the idea that he had internalized as a kid, that there was something wrong with him, took a long time to overcome. He had to consciously unlearn those beliefs, even after being out and living openly as a gay person. And it was his lifelong Vulcan training that helped him in this process.

Christian Cooper:

I try to parse things unemotionally, and I’m like, “All right, so who is being harmed here? Being this way and living this way, what is the harm to others?” And as I thought it through more and more and more and more and more, I was like, “There ain’t none. There is no harm. So why waste energy fighting it?”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And once he made that rational decision to stop shaming himself for being gay, instead of fighting himself, he began to channel that anger outside of himself. And when we come back, we’ll talk about how Christian went from being a queer kid buried alive in the closet to being the person he is today, an everyday superhero who stands up for himself and others. On top of his love for the outdoors, there was something else Christian’s father passed down to the Cooper family, his activist gene.

Christian Cooper:

And there were pictures of my mom holding my sister’s hand and pushing me in a stroller at a protest. Even though we didn’t see a lot of it by the time we got older, it was there. We knew it. And nobody ever said this explicitly, but it was just very clear in our lived experience that, if you saw something wrong with the world, it was your personal responsibility to try to do something to fix it.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And during that time in his life, as a young gay Black man living in New York City in the eighties, Christian saw a lot of things that were wrong with this world that he wanted to change.

Christian Cooper:

I, at the time, was co-chair of the Board of Directors of the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, or GLAD. And we sponsored a rally, and it was actually a rally against anti-gay violence that had happened in Manhattan. And afterwards, they were going to block traffic on the streets and sit down and do a sit down protest, the kind of thing my parents would’ve done back in the civil rights day. And I was just like,” I, as one of the organizers of the rally, cannot let all these people sit in the street and get arrested and stand on the sideline.” So I sat down in the street, joined the sit-in protestors, and we all got arrested. To me, it was like, “Oh my God, I’ve never been arrested in my life. What’s going to happen?” And they take you to the police station. They give you a little desk appearance ticket and send you home. And I’m like, “Oh, okay.” So anyway, so I got home later that night, and there was a message on my answering machine. We had answering machines back then, and I played it back. And it was my dad.

And he said, “Oh, I saw on the news that there was a protest in Manhattan and that people got arrested. So I just wanted to call and make sure that you were okay.” And this was huge for me. This was the first time we had talked about my being gay. That part, I had kept carefully sequestered. Even though I had come out to him, we had never talked about it ever since. And this was him bringing it up. And here he was reaching out to me, connecting on something that was so important for him, because he had done the same thing in his youth. He had been arrested in civil rights protests back in the day. So that was, to me, a big sign that, “Okay, maybe I don’t have to keep this part of my life sequestered from him anymore.”

Please, call the cops. Please, call the cops.

Woman in Park:

I’m going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.

Christian Cooper:

Please tell them whatever you like.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Looking from the outside, it might seem that the viral video that Christian shot in 2020 with its 40 million views was the thing that changed Christian’s life. But the thing is, Christian’s transformation came before that day at Central Park. It was actually a series of many transformations that happened over the course of his life.

Christian Cooper:

I think we all have to slowly unlearn the self-loathing that we are taught by society.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

When Christian’s dad left that message on his answering machine, something changed. It was the first time Christian felt like his dad really accepted the queer part of him. And Christian realized he doesn’t need to hide himself anymore, not from his dad and not from the world. And fast forward to that fateful day in Central Park.

Christian Cooper:

Please tell them whatever you like.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

All of the transformations that Christian had cultivated throughout his life really prepared him for that moment.

Christian Cooper:

I just tried to deal with it as any good Vulcan would, very rationally. I just tried to… As fraught as all the emotions were at that moment, I was like, “Okay, I’m not going to deal with this emotionally. I’m going to stick to my guns.” I think that served me well.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And it did serve him well.

Christian Cooper:

For better or worse, with what happened in Central Park, a certain degree of power fell into my lap. And my attitude was, “If you’re going to shove microphones and cameras in my face, I’m going to use them to say what I think needs to be said, and I’m going to try to use it for what matters.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And what matters to Christian is, of course, advocating for birds.

Christian Cooper:

Since 1970, since I’ve been birding, the number of birds total in North America has gone down by about a third. And I see it. I feel it, when I’m out there.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

There are birds that Christian and that none of us would ever see again, because they’re gone forever. And that loss is growing.

Christian Cooper:

They’re part of us. And to let them go, we’re not getting them back. Imagine how impoverished that would be.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But the declining bird population is not just bad news for the birds.

Christian Cooper:

They are our early warning system for the environment. So they are a very visible part of the ecology. Often relatively high up in the food chain, they are literally the canary in the coal mine, that, when there is something wrong with the ecosystem, we can see the impact in the birds. So the birds are sending us a warning that our ecology is in trouble.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And when we work to preserve the bird population, it will have ripple effects through the entire ecosystem.

Christian Cooper:

To protect these birds, we protect their habitats, and that means we’re protecting a whole range of other species’, big and small. And we’re protecting ourselves, because, for example, when you allow there to be a wetland in a coastal area, that wetland can serve as a barrier to flooding, which is a growing problem, as sea levels rise, because of global warming. So we have to stop thinking in such discreet terms of, “Oh, there’s us humans and then, the rest of the world. And let the rest of the species be damned.” No, that’s not the way it works. This whole planet is a big web of connections, and the birds can serve as our early warning system in that web.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And for Christian, part of bird conservation is actually advocating for the Black and brown people who’ve been left out, not only from birding, but from having access to nature.

Christian Cooper:

A lot of Black and brown people these days are in urban environments, where nature is not immediately apparent. So I think, for our organizations, we need to be in those urban settings to try to reach out to folks and make sure that they know that nature is for them too and is right outside their window.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

For Christian, this means getting more people to notice the birds. And the way Elliot, his birding godfather, had nurtured his interest in birding, Christian hopes to do the same for the young people in his city.

Christian Cooper:

I’ve been going into schools for years in New York City public schools and getting kids outside, away from concrete, pavement, and cement, and into green spaces looking for birds. There was a group of kids we took out for the first time, and we showed them sparrows, just the regular old house sparrows that you can see on any city street. And they’re like, “Oh, you mean those aren’t baby pigeons?” “No, that’s actually a different species.” And then, suddenly, the idea of species comes up, and then, you start teaching them little mnemonics for the songs. One of my favorites was teaching kids in the Bronx that they should be listening for. (Singing).

And suddenly, they realize, “Oh, wait a minute. You mean I can tell birds apart by the sounds they make?” And then, suddenly, they’re out in the park, and they’re like, “I hear a warbling vireo. I hear a warbling vireo.” And then, they’re going, (Singing). And I’m like, “Okay, mission accomplished.” So this is when you say we’ve got to get people involved. How do we get Black and brown people involved? How do we reach into other economic groups, besides the middle class and the upper middle class? You meet people where they are, you bring birding to them and make them realize that, you know what? This is for you too. And the birds are for everyone. (Singing)

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And you know what? Christian is right. The birds are for everyone. Nature is for everyone. But if the goal is to make sure that Black and brown people know that they too have a place in nature and in birding, it’s not enough to just get Black and brown people to notice the nature outside of their windows. The birding community has the responsibility to actively draw people in. They need to make nature and birding and conservation not just welcoming, but also, safe for everybody, which is why the Audubon name controversy is such a big deal.

Christian Cooper:

A lot of people say, “Well, but it was so long ago. Why worry about the past?” We’re not worried about the past. We’re actually trying to look forward, rather than back. And what we’re facing is a lot of Black and brown people who have never been active in birding, who we have to bring in, if we’re going to save the birds. And as the awareness of Audubon’s past and as racism gets out there, it’s going to make people think, “Why the heck do I want to join an organization named after a slave owner?” Black people have a very strong reaction to that. We do not respond well to that.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

No, we don’t. Because to me, it’s more than just about the name. If I’m encountering this organization for the first time, it would send me all kinds of red flags. Because if you’re okay with naming your organization after a man who’s a racist and a slave owner, well then, what else are you willing to overlook? What kind of micro and macroaggressions am I going to have to deal with when I step within your organization?

Christian Cooper:

Why would we choose to subject ourselves to that indignity, when we have other choices about what we can do with our time? And we cannot afford to make it harder for Black and brown people to get involved in birding? And if we do not expand birding beyond an all-white base, the birds are done, because there will be no constituency to fight for, to vote for, to support the birds and their habitats.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So despite the lifelong associations Christian had with the Audubon and all the things that the organization had brought to him, he knew what he had to do.

Christian Cooper:

And so, I had to really separate out the emotional aspect of it and really focus on, what is Audubon’s mission, which is to protect the birds. And to fulfill that mission, we’ve got to get more Black and brown people involved. And if we’re going to do that, the Audubon name is just going to make it harder. And that was what tipped the decision for me.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

In March, 2023, Christian, along with the other board members of the New York City Audubon, voted to drop the name “Audubon” from their local chapter. As of the recording of this episode, National Audubon has not shown any signs of reconsidering their decision. But I’m thankful for board members like Christian and all the other local chapters who are fighting to make this change on their own, because they’re sending a message to people in and outside of the birding community, that everyone’s safety matters. And to me, that makes them true heroes.

Christian Cooper:

You know what? We’re all superheroes. We all have a certain measure of power that we have in our lives. We have a lot more power than we are led to believe. And I think, in all of us, it is incumbent to take the power we have and use it responsibly to try to make the world better for everybody.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Christian Cooper’s new memoir is called Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World, and he has a new special on National Geographic called Extraordinary Birders.

We’d like to take a moment to acknowledge the native lands that make up New York City, the location where many of Christian Cooper’s stories took place. We acknowledge and honor the homeland of the Lenape, the Matinecock, the Maspeth, and the Canarsie peoples. Indigenous peoples have inhabited these lands for more than 10,000 years. From time immemorial, the native populations have been caretakers of their natural environment. Agricultural customs on these lands included farming, hunting, fishing, and gathering from the flourishing bounty that was provided.

But it has been a difficult and tragic history for the region’s indigenous peoples. The end of their lifestyle began with the arrival of European settlers in the early 17th century. The struggle over land began despite the efforts of the tribal peoples to live in peace with the newcomers. The so-called selling of Manhattan Island to the Dutch for $24 is a myth that remains nonetheless an iconic story of American history. The Lenape lands, called Lenapehoking by the original people, included the areas from New York City to Philadelphia, all of New Jersey, Eastern Pennsylvania, and part of Delaware.

Most Lenape now live in federal and state recognized political sovereigns in Oklahoma, Canada, Wisconsin, and New Jersey. Most Lenape were driven from their original homeland by settler encroachment in the 18th century. However, many Lenape still live in New York City where they continue to practice their traditions. In the 1930s, some Matinecock graves were discovered in a road widening project and reburied with a plaque that read, “Here rests the last of the Matinecock.” Obviously, someone forgot to check with the Matinecocks.

But Matinecocks still number some 200 families that live in and around the borough of Queens in the same area where they’ve resided for a thousand years. Although they’re not federally or state recognized, they are a thriving tribal community actively engaged in land reclamation. It must be said that New York City has the largest urban Indian population in the entire country with a population of over 180,000. The American Indian Community House of New York serves the interests and needs of the urban native people. It’s also where contact can be made for information on the public activities of the city’s indigenous people.