NATURE: You’ve studied elephants for more than 15 years, could you give us a sense of how elephants are doing overall? Is there some yardstick by which we can measure how African elephants are doing as a species?

Unfortunately, elephants are facing their bleakest moment in the last 100 years. This is a dark time in the history of elephant conservation. I’ve just finished flying an epic aerial survey called the Great Elephant Census, that has attempted to estimate how many elephants are on the African continent. And the results from that study are really shocking. Over a seven-year period, it’s estimated that 144,000 elephants have been killed, largely because of the ivory poaching crisis. That number translates to about 30 percent of Africa’s elephants.

NATURE: How many elephants do we think existed in Africa before human civilization had taken hold there?

It’s difficult to get reliable estimates, but in my estimation the African continent would have been riddled with elephants–possibly in the tens of millions. We know that when Iain Douglas-Hamilton conducted his elephant census in the 1970s, he estimated close on 1.2 million elephants. Our Great Elephant Census, nearly 40 years later, has estimated just under 400,000 elephants. So that is a catastrophic decline over a relatively short period.

NATURE: So you’re saying that even more recently that this decline has increased, is that right?

It has indeed. Our mortality rate suggests that the elephant population is declining by eight percent every year. For the first time in nearly 40 years, elephants are dying faster than they can recruit, so the death rates are higher than the birth rates.

NATURE: Could you tell us a little more about the Elephant Census? And how did you arrive at these numbers?

The Elephant Census was flown across nearly 18 elephant range states, involved nearly 100 scientists from across Africa, and it involved flying at low-level altitude in a fixed-wing plane mounted with high-resolution digital cameras and typically three observers, a data recorder. Every time an elephant herd was observed, it was counted. And to verify the observers’ call outs, photographs were also taken, so we could subsequently go back and accurately estimate how many elephants were seen. So we used state-of-the-art technology, and running complicated statistical analysis, we were able to come up with a really precise and accurate estimate on the number of African [savanna] elephants are left on the continent.

NATURE: How long did that take to scan that much area? A year or longer?

It took us two years, and it was a daunting exercise. When I first announced the Great Elephant Census, there were a lot of naysayers, and people thought it would fail within the first year. But secretly, I didn’t share their doubts. There was a lot at stake. This is an animal that’s in peril and armed with accurate and robust information, we hoped that data would shock people out of apathy. And it certainly has. We’ve seen a huge transition in the last year. The public are certainly more aware. Governments have come on board. China has agreed to close down all its ivory carving factories. So there’s genuine concern for the plight of the African elephant.

But unfortunately, many of the populations are still threatened, if not by ivory poaching, by rapidly growing human populations. Elephants need space. This is the world’s largest land mammal, weighing nearly six tons, and they have huge home ranges. They can embark on epic journeys. Our elephants in Botswana can move upwards of nearly 600 miles in a month. Unfortunately, land that used to belong to elephants has been converted to development, farming, and just human population pressures. Half of the elephant range states’ human population are projected to double in the next 50 years, meaning that many small, isolated elephant populations will probably become locally extinct.

NATURE: Even if we were able to stop poaching completely, which doesn’t seem feasible right now, but would this habitat encroachment still be put elephants at risk? How big of a role does poaching play in the decline that we’re seeing?

Certainly, the ivory poaching crisis is exacerbating the rate of decline in African elephants. It’s made worse by habitat fragmentation. Elephants need space, and Africa’s human population is just growing at an increasingly rapid rate. The highest human population growth rates in the world are found in Sub-Saharan Africa. So if we, by some miracle, happen to stop elephant poaching, elephants would still be endangered by habitat fragmentation and that’s the great tragedy of elephant conservation. They’re just facing incalculable odds from climate change, poaching, habitat fragmentation, human-elephant conflict, droughts, and increasingly being pushed into smaller, smaller islands in which to eke out a living.

NATURE: You’re saying this combination of all these human activities, it’s putting great pressure on them.

It is. There are some beacons of hope. People have asked me after flying the Great Elephant Census if I’m an optimist or a pessimist about the future. I’m a die hard optimist. I have faith that elephant biologists and the public around the world are genuinely concerned about the plight of the elephant. If I take my country for example, Botswana, my home, we have a government and politicians who are extremely dedicated and committed to preserving African elephants and our wildlife because we understand that ecotourism is a large foreign exchange earner and brings in hundreds of thousands of tourism visitors to our country every year. So our tourists are seeking out Botswana’s wildlife, its large elephant population, the largest in Africa, and wilderness areas, and we’re gaining from successful conservation practices.

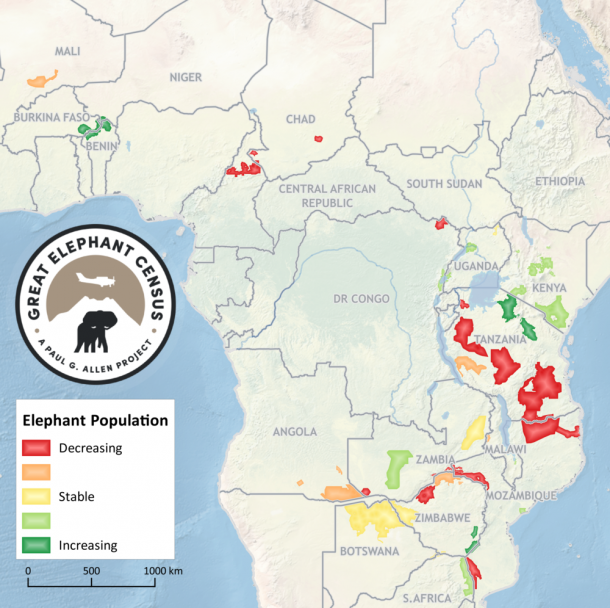

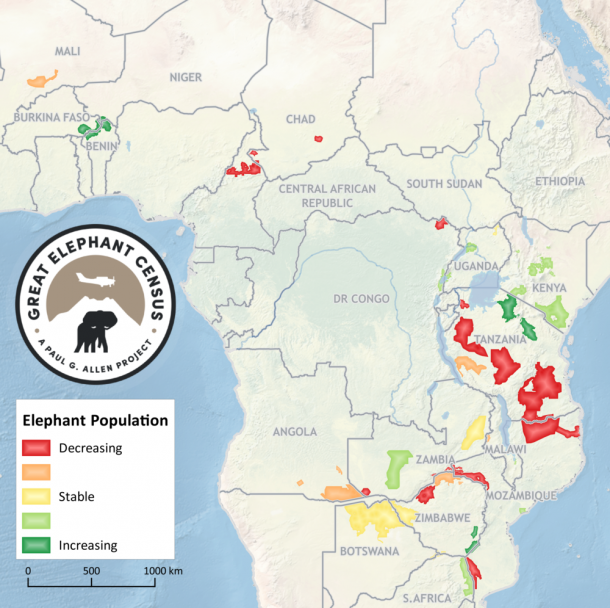

NATURE: The Great Elephant Census found that overall, elephants have declined, but you have a great map [see below] that was a result of this study, which show that some countries seem to be doing better in terms of elephant conservation. Could you talk a little bit about that and why is there this disparity between different countries?

Credit: The Great Elephant Census

That’s the great irony of elephant conservation. They’re doing well in some countries, we have healthy populations, and in others, they are all rapidly declining. This can largely be attributed to the commitment and dedication of the governments who are less corrupt, are determined to safeguard their wildlife population because of its importance to ecotourism. We can’t be complacent. Here in Botswana and in Southern Africa, what we have seen is that the poaching pressure that was in West, Central, and East Africa is now filtering south. And we are seeing early warning signs of the poaching crisis possibly extending well into Southern Africa, into southeast Angola, southwest Zambia, parts of Namibia, and certainly parts of Botswana.

NATURE: What are governments doing that is most effective to protect elephants?

I can only speak of my experience in Botswana where the government has ensured that the Botswana Defence Force have been deployed to protect our wildlife along our international borders and indeed well within the elephant heartland, the elephant range, so we have effective anti-poaching units. Our wildlife laws and arrests and prosecutions have made it increasingly more difficult for people to commit these crimes. Wildlife trafficking is being given a lot of attention. I can only speak of the case in Botswana where we have very dedicated statesmen to protecting our wildlife heritage.

NATURE: Elephants tusks, known as elephant ivory, are what drives poaching. Some animal products like rhino horn are worth more than their weight in gold. Is that true for elephant tusks as well?

Arguably, this is the most precious and expensive organic material on the market after rhino horn, is elephant ivory, elephant tusks, which are extensions of their upper incisors and can weigh anything from a few pounds up to 100 pounds. It’s these large tuskers which poachers are typically identifying. We’ve lost some really iconic, mammoth African elephants in the last five years to poachers who have sought them out specifically because they’re carrying long symmetrical ivory that reaches down to the ground. Unfortunately, contrary to popular belief in Asia … They think that you can harvest these teeth without actually killing the elephant, but all evidence is to the contrary. Poachers leave African landscapes littered with rotting carcasses from elephants that they’ve killed to cut out these tusks.

NATURE: Do we know what we can do to curb the demand for this ivory?

Well, we have campaigns around the world, which have gained momentum, documentary films, popular news articles, interviews like the one I’m giving you. People in Africa giving voice to the plight of elephants is frightfully important. We’ve just got to carry on. We can’t give up. We’ve got to let people know that these animals are really on a knife edge. And if we continue the rate that we are going, in 10 years time, Africa will have less than 200,000 elephants, and certainly, many will be locally extinct in many parts of their ranges. And that the poaching crisis is extending. Poachers and wildlife traffickers find new hot spots throughout the continent in which to focus on, and currently, it appears that they are moving further down south.

NATURE: People probably aren’t aware that poachers target specific area and basically wipe out entire local populations of elephants.

In many cases, in areas that we flew over, I’m sad to say that we counted more dead elephants than live elephants. That wasn’t uncommon. There were days when I thought that the only good I was doing was recording the disappearance of one of the most remarkable animals that walks our planet. That was really depressing. I thought that the Great Elephant Census, a project which, when I started, was filled with romance and anticipation and excitement about possibly counting vast herds and numbers of elephants. It dawned upon me halfway through the Great Elephant Census that all I was doing as an elephant biologist was recording the annihilation and slaughter of one of the most charismatic animals that walks our planet.

NATURE: That is depressing.

Any wildlife biologist or conservationist who comes to the realization that he’s maybe fighting a losing battle, that’s a very daunting and difficult thing to get over, but we persevered. I’m using the Great Elephant Census now, the power of incredible data to drive and motivate for change. We are seeing reduction in poaching in Tanzania, Kenya, Mozambique. The Great Elephant Census really motivated those governments to realize, “Wow, if we don’t do something now and act very quickly, these elephants and these populations could disappear from our countries.” These are symbols of Africa. African elephants are emblematic of our struggle to save Africa’s wildlife, and if we can’t save the African elephant, what is the future for the rest of Africa’s wildlife?

NATURE: Your organization is called Elephants Without Borders. Why is this concept of “no borders” so important?

Elephants, to me, represent a massive liberty. I was fortunate during my PhD study to collar nearly 100 elephants which embarked on epic journeys, many of them across international borders passport-free. So this notion that elephants had the freedom of Africa, could wander across political boundaries really struck a chord with me. I came back home, and based upon the results of my PhD study, these massive free-flowing movements of elephants, started an NGO called Elephants Without Borders. That’s the world that I would like to see us humans, in some small way, replicate. They have the freedom to cross landscapes, contiguous ecosystems and are not constrained by political boundaries and barriers that are put in place.

NATURE: So as these elephant populations exist today, do they have that freedom of movement? Or are they more confined to sort of sanctuaries that keep them safe from poaching?

Unfortunately, the notion and philosophy which we built Elephants Without Borders on, has fallen flat on its face. Elephants within Botswana don’t embark on these epic journeys anymore. They stay within Botswana’s borders where they seek sanctuary and refuge because they are safe. So because of the poaching crisis, elephants are frightfully intelligent, know where they are being persecuted, know where they are safe, and so have sought sanctuary well within Botswana’s

NATURE: It really sounds like this is a very complicated problem, and there’s a lot of factors that contributing to the decline in African elephants. But for people that aren’t on the ground in Africa, what can we do to help? Do things like ecotourism help? It sounds like even tangential things like helping Africa slow its population growth could help.

I always encourage people to come and see elephants in their natural habitat, so eco-travel. Take a safari to where you can see elephants in the wild, and your money is well-spent on conservation efforts. A lot of the tourism lodges that you will stay at have a bed levy, which contributes to conservation, pays for anti-poaching units, pays for schools and clinics, education and awareness programs. At the same time, the travelers gain a greater insight into the challenges and threats of conservation in Africa, and you get to see the most remarkable land mammal in person. So I would certainly encourage people to take a safari to Africa because that would be money well-spent, not only on them but in preserving an extraordinary animal.