The Untold Story of California’s Mighty Predator

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Today, we’re going to talk about apex predators, but we’re starting at a place that you wouldn’t normally expect to find large carnivores roaming around right in the heart of Los Angeles. Griffith Park is this famous urban park in LA, so picture sprawling hills covered in trees and shrubs, just an island of greenery surrounded by freeways. And nestled in these hills is the iconic Hollywood sign, and all around it are wilderness areas where you’ll find native wild animals roaming around, including this one particular mountain lion. And you might know the exact mountain lion I’m talking about, especially if you’re from Southern California because this mountain lion made the news for traveling all the way from the Santa Monica Mountains down to Los Angeles, crossing 10 lanes of the freeway and then setting up camp at Griffith Park for over a decade.

And as impressive and fascinating as it is for a mountain lion to survive in the middle of Los Angeles, it’s actually really tragic because the truth is Griffith Park isn’t exactly a suitable place for a mountain lion to live. Even though it’s a big park, it’s not nearly big enough for such a wide-ranging animal to thrive. And in fact, it’s the smallest territory ever recorded for an adult male mountain lion. Like imagine how isolating and lonely it is to be a mountain lion, an apex predator that requires a wide range of territory, but instead you’re confined to this island of wilderness surrounded by impenetrable freeways and then having to spend your entire life alone, not able to find a mate. So originally we were going to do a whole story on this mountain lion, but then things got a little bit complicated.

Desiree Martinez:

I don’t know how it could be handled so that we’re not bringing his name up because the mention of his name in our belief system that hinders the journey of that relative into the afterlife.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

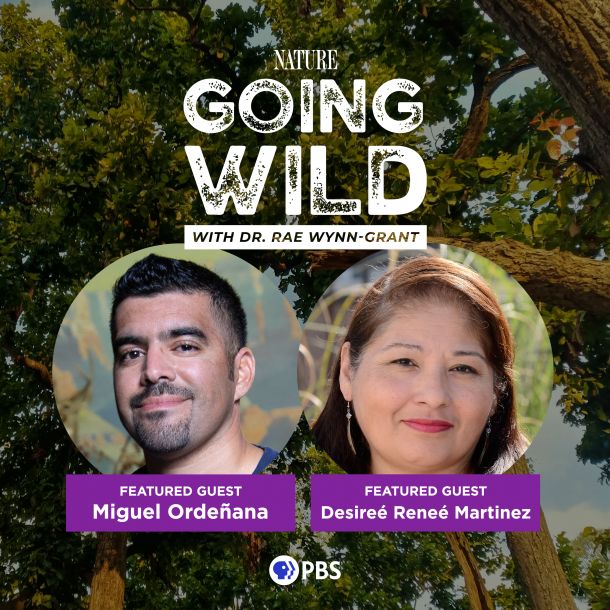

I’m Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant, and this is a different kind of nature show, a podcast all about the human drama of saving animals. This season we’re going to take a journey through the ecological web from the tiniest of life forms to apex predators. We’ll hear stories from scientists, activists, and adventurers as they find all the different ways the natural world is interconnected. And together we’ll explore our place in nature. This is Going Wild.

Desiree Martinez:

I see the importance of this topic, but I also want to be respectful of the request of the elders. It’s difficult to practice our cultural values in a modern world.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

This is Desiree Martinez. She’s an archeologist and a member of the Tongva community, which is one of the indigenous tribes in Los Angeles. If you’re a regular listener to this podcast, you know that on top of saving animals and conservation, we also talk a lot about how gender, race, someone’s history, and life experiences, all of those things cannot be separated from the science and the work that they do. And for Desiree, this is especially true because as a scientist and historian whose work often includes educating the public, sometimes that work clashes with her traditional Tongva values, which is exactly what happened as we were pursuing this story. So to help explain all of this further, I’m actually bringing in one of our amazing producers, Caroline Hadilaksono. So, Caroline, can you please help explain to us before we properly get started, what exactly happened?

Caroline Hadilaksono:

Yeah. So the Griffith Park mountain lion, he passed away this last winter in December 2022. And there was a debate between the Natural History Museum and the local indigenous communities about what to do with his remains. And I want to say upfront that after some talks between the museum and the tribes, this particular debate was successfully resolved. But this misunderstanding, even though it’s resolved, it really brings to light the longstanding exclusion and marginalization of indigenous communities from conservation, from wildlife management work, and from just the dominant culture as a whole. And for a little backstory, I called up Miguel Ordeñana from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. He was the wildlife biologist who first discovered this mountain lion living in Griffith Park. He had been tracking the mountain lion closely all these years, and Miguel had applied for a permit to collect his remains.

Miguel Ordeñana:

The goal was to make sure that his body wasn’t destroyed because the traditional thing that happens with even study animals is that there’s a necropsy done when they die and tissue samples are collected and then they’re cremated. But the museum’s role is to act as a repository for future research opportunities. But if he’s cremated, there’s no opportunity. So that was the intention, but because it was such a popular story, as soon as it hit the media, indigenous groups were very concerned.

Caroline Hadilaksono:

They didn’t know what the museum was planning to do with the body, and the tribes wanted the body to be returned to them so they could perform a burial ceremony because the indigenous communities in the area, don’t view animals the way a lot of us do. So this mountain lion wasn’t just a predator that roamed Griffith Park, he was a respected member of their community. They see this mountain lion as an ancestor, one of their relatives, which isn’t some small thing. It’s actually a fundamental way of how they view the world. That’s very different than the mainstream American worldview where we don’t have that same kind of reverence for animals and nature.

Miguel Ordeñana:

Even though my intention was to have those conversations with tribal groups once he arrived at the museum, they didn’t know that that’s kind of really, I don’t know, arrogant of me to assume that tribal groups or any group knows my intentions when I’m writing a permit.

Caroline Hadilaksono:

In the end, the museum and the tribes did reach an agreement, and the tribes were able to perform a burial ceremony for the mountain lion. But that’s where things got a little bit tricky for us in terms of producing this episode because when I called Desiree, this is what she told me.

Desiree Martinez:

Part of our morning ceremony for humans is that we don’t speak the name of the relative for a year.

Caroline Hadilaksono:

As you might expect, given their worldview, this morning tradition doesn’t only apply to human relatives. The Tongva and other indigenous tribes in the area consider all kinds of life to be a relative including mountain lions. And that means for the next year, they will be observing this morning tradition for the Griffith Park mountain lion as well, which means they can’t mention his name and we can’t mention his name.

Desiree Martinez:

I don’t know how it could be handled so that we’re not bringing his name up because the mention of his name in our belief system hinders the journey of that relative to the afterlife.

Caroline Hadilaksono:

During our conversation, I could tell that Desiree was being careful, and referring to the mountain lion only as her relative. So she doesn’t have to mention him by name, but it’s more than just simply not saying his name.

Desiree Martinez:

Even me, just referencing him, I really shouldn’t be doing, but I’m not calling him by name or anything like that. And I might get slack from the elders about it, but I see the importance of this topic, but I also want to be respectful of the requests of the elders. And so it’s difficult to practice our cultural values in a modern world.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Yeah. Gosh. I can see how Desiree is wrestling with this double bind. On one hand, she wants to be respectful of her traditions by not talking about the relative that they recently laid to rest. And then on the other hand, she’s right, this is a really important topic to talk about.

Caroline Hadilaksono:

Yeah. But our team has also been wrestling with this double bind as we’re producing this episode. We weren’t sure what would be the best way to handle all of this, but Desiree actually had a suggestion, a sort of compromise where we could tell this story and still honor the morning tradition.

Desiree Martinez:

I think it’s not the focus. So if you were to open up the podcast summarizing what happened, making sure that the audience knows the reason why you’re being careful.

Caroline Hadilaksono:

And that’s exactly what we’re trying to do here. And because the tribes only performed a burial ceremony for the Griffiths Park mountain lion, they’re only observing the one-year mourning tradition for this one particular mountain lion. So I asked Desiree if it was okay for us to talk about other mountain lions in Southern California, even ones that have passed away.

Desiree Martinez:

Yeah, that’s fine. I mean, because we ceremonially put him to rest. We are not supposed to mention his name. For all of the other mountain lions that have passed, we did not do a ceremony for them. We don’t even know who they are other than a number that’s on a database somewhere.

Caroline Hadilaksono:

Because these other mountain lions in Southern California weren’t as famous, they didn’t really get the same kind of media attention, and their deaths didn’t receive as much scrutiny. So when they passed away, there wasn’t any public pressure to make sure that the local tribes were consulted. And so there were no conversations about what to do with the remains of these mountain lions.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So that means they never even got the chance to perform a burial ceremony for any of them.

Caroline Hadilaksono:

Yeah. But because there was no burial ceremony, the tribes aren’t observing the one-year mourning tradition for them, which means we are actually able to share their story.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

I hate that the local tribal groups never got a chance to properly lay to rest so many of these mountain lions who are considered to be their relatives. But since we are able to respectfully share their stories, I believe one way to honor the local tribe’s relatives is by telling their stories. So instead of the Griffith Park mountain lion, we are going to tell you about all the other mountain lions in Southern California, the ones who don’t live in Griffith Park and who aren’t in the spotlight because all of these mountain lions are actually a big part of the history and the future of this state. Here’s Miguel again.

Miguel Ordeñana:

Mountain lions have been here since the ice age and before the ice age.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

That’s 40,000 years that they’ve been around. And there were several different species of big cats in Southern California during the ice age, including the saber-toothed cat and the scimitar-toothed cat with their long sharp teeth. But those sharp teeth didn’t ultimately help them through the centuries, it was the mountain lions that proved to be the most resilient of these apex predators.

Miguel Ordeñana:

Mountain lion was the only one to survive the ice age extinction,

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And they’re still here today roaming the hills of Southern California. And that’s because mountain lions are super adaptable. They can eat different types of prey and survive in different types of habitats.

Miguel Ordeñana:

So to this day, you can find mountain lions in wetland ecosystems, mountainous areas, and deserts, and that speaks to the animal’s resilience. And they really worked hard and adapted well.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But here’s the kicker. Despite outlasting all the other big cats and surviving in California for some 40,000 years-

Miguel Ordeñana:

It’s finally meeting its match because of our selfishness and our need for convenience and other luxuries that have fragmented its habitat through the building of freeways, and residential areas up against mountain lion habitat.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Mountain lions are solitary wide-ranging animals. Their average territory is around 200 square miles, which for reference, Griffith Park is way smaller than that, like 25 times smaller. I mean, imagine if your house was 25 times smaller than it is now. But Griffith Park is not the only wilderness island that’s cut off by freeways and urban development. This kind of habitat fragmentation is also happening outside of Los Angeles County and all along the southern California coast. Since 2002, the National Park Service has been studying how the increasingly urbanized landscape of Southern California has affected the mountain lion population. Researchers have collared and tracked more than 100 mountain lions in and around the Santa Monica Mountains, which is 40 miles north of Los Angeles.

Speaker 5:

Wildlife lovers are mourning the death of yet another iconic mountain lion P-81.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Earlier this year, in January 2023, one of the collared mountain lions passed away.

Speaker 5:

Wildlife officials believe P-81 was killed by a passing car.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Researchers called him P-81 since he was the 81st mountain lion to be studied. And because the local tribes weren’t informed about his death at the time, P-81 didn’t receive a proper burial ceremony, which is why we’re even mentioning his name. P-81 was only four years old when he died. His body was found on the Pacific Coast Highway in the Western Santa Monica Mountains. Vehicle collisions are one of the leading causes of death for California Mountain Lions.

Speaker 5:

P-81’s death now means nine mountain lions have been hit and killed by cars since March of 2022.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

P-81 was notable in the mountain lion study because of a physical abnormality that he had. The end of his tail was shaped like the letter L, and this kinked tail is the physical evidence of the lack of genetic diversity in this mountain lion population. And that’s due to the fragmentation of its habitat. When a mountain lion reaches one and a half to two years old, they leave their mothers to find new territory. But because freeways and urban development have created these impenetrable walls, mountain lions aren’t able to move freely to other territories. And then this leads to inbreeding. The inbreeding is the reason why these Southern California mountain lions have the lowest genetic diversity of any mountain lion population on the West Coast. And not only will this lead to birth defects like P-81’s kinked tail, but eventually it’ll lead to the inability to reproduce altogether. And without reproduction, these mountain lions won’t continue to survive in California.

Miguel Ordeñana:

And so mountain lions, although they were such a resilient animal or still are, are on the verge of extinction here in the LA area.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Imagine after surviving the ice age extinction and being on this land for 40,000 years, and now this population of mountain lions might just disappear forever. But California mountain lions aren’t the only native inhabitants of this land that have been systematically pushed out. The Los Angeles basin and the four Southern Channel Islands off the coast of California are the home of the Tongva Tribe, also known as the Gabrieleño Tongva.

Desiree Martinez:

Our community emerged from these lands, and so we’ve been here since time immemorial.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

This is Desiree again, as a member of the Tongva Tribe and an indigenous archeologist, Desiree works to protect sites that tribal communities find important and sacred. And a big part of this work is in covering the history of the Tongva community.

Desiree Martinez:

One of the reasons why I chose archeology as my profession was because of a trip that I took to the Southwest Museum in the fourth grade. At the time, in the mid-1980s, the Southwest Museum was the only place where you could learn about California native people. And so we went on a field trip with my class, and as the docent was talking about the Mission Indians, one of my friends raised our hand and stated, “Are there any Mission Indians left?” And the docent said, “No, they’re extinct.” And the Gabrieleño Tongva are considered part of that Mission Indian group.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

At the time, the different indigenous tribes in California were grouped together and referred to as the Mission Indians because they were forced by the Spanish to convert to Christianity and become part of the mission system.

Desiree Martinez:

And so at that time, I knew that my family and I were still alive, so we weren’t extinct. And I had a lot of classmates ask me, they just said, “You’re extinct, so how could you be Gabrielino?” And also at the museum, they had little dioramas of what Indian life was, so half-naked people living in traditional houses. And it’s like, “Well, you don’t live like that, you live like us, you dress like us. So how can you be native?” And so I knew that I wanted to do something in order to change that opinion that we were extinct.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And because historians rely on archeological and anthropological findings, Desiree knew that the way to rewrite the history of the Tongva people would be by uncovering and reconstructing the true history of her people. And that’s not an easy task because the indigenous peoples of California, along with their cultures, have been systematically erased.

Desiree Martinez:

One of the big things about being a native person here in California, there were actually bounties on Indian heads and scalps. And so a lot of our communities went underground. And because they were part of the mission, a lot of our community spoke Spanish. They were wearing the clothing of what would be considered a Spanish or a Mexican peasant, and so it was easier to just blend into the community that surrounded them hiding in plain sight.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And the fact that they had to hide their culture has huge repercussions. Even to this day, the Gabrieleño Tongva and a lot of indigenous tribes in California aren’t able to get federal recognition.

Desiree Martinez:

We never had a written language. We, in some instances, a lot of the communities were illiterate. And so you didn’t have people from our community writing our own history. So that lack of documentation is the biggest stumbling block to getting federal recognition.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Without federal recognition, the Tongva tribe doesn’t have access to the resources they need to reclaim their culture and sovereignty.

Desiree Martinez:

Federally recognized tribes have reservations, lands that were set aside in which the population could live on. The Gabrielino Tongva don’t have that. And because we lack a land base, it’s very hard for us to reestablish that relationship that we have with our relatives and to create spaces to meet as a community, whether it’s to perform ceremonies or to have cultural gatherings, or talk to the public about our history.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Without federal recognition as a sovereign tribal group or a designated central gathering space, what’s left of the Tongva culture is kept alive within each family passed down through generations by practicing their traditions in private.

Desiree Martinez:

Although you would be a practicing Catholic, you still had various ceremonies, naming ceremonies, puberty ceremonies, mourning ceremonies that would occur like sometimes in the dead of night or out of the public view in your backyard or somewhere else on the lands where there was nobody around.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And on top of continuing to practice these ceremonies, the Tongva community is also reclaiming their culture by reconnecting with their ancestors, especially those who’ve been harmed and disrespected by colonial institutions through the destructive excavation of their burial sites.

Desiree Martinez:

And so a lot of times these excavations were done under the cloak of night without the permission of the people who were related to these individuals. And these items would be placed in cabinets of curiosity, is what they would end up being called. So anything that was weird or they had never seen before would be put on display. And these cabinets of curiosities were basically the first museums. One of the big things that was instilled in me is the sanctity of the grave, that if you are anywhere near where ancestors were buried, that you’re not supposed to disturb them, that you’re going to be quiet, you’re going to be respectful. And that’s what we’re trying to get other people to recognize as well, is that we have rights as human beings to continue our journey after our death and not have to worry about being dug up or our graves being desecrated. And so this has caused a lot of trauma and both spiritual, physical, emotional trauma to those communities, and still continues to create that trauma.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

All of these colonial forces that pushed the Tongva and other indigenous peoples off their native lands, fragmented their communities, and destroyed their ways of life have shaped and are continuing to shape California’s landscape to this day, both culturally and also literally. This colonization is fracturing ecosystems and thus pushing California’s native inhabitants, including its wildlife off their land and destroying their way of life. And for the mountain lions, this fractured landscape might lead to extinction unless we take action. When we come back, we’ll find out just how southern Californians are taking action by literally paying the price to undo the damage that’s been done to the land.

As apex predators, mountain lions have a huge role to play in the ecosystem because the population of organisms on the bottom of the food chain is controlled by the organisms at the top.

Miguel Ordeñana:

It is the primary predator of at least one or a few species of prey. In the case of a mountain lion in Southern California, at least they eat about a day or a week.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So apex predators keep herbivore populations in Czech and in turn, that ensures that vegetation in the ecosystem isn’t being overly exploited.

Miguel Ordeñana:

Also, it’s one of those predators that is very timid and a lot of times abandons its kill. And when it abandons its kill, those remains benefit the rest of the ecosystem all the way down to decomposers.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And mountain lions are not only crucial to the ecosystem as apex predators.

Miguel Ordeñana:

Another thing that is important to note about big cats and large carnivores is that because they’re wide-ranging animals, they have these huge territories. To save those species, you’re going to be setting aside huge areas that not only benefit those mountain lions but also benefit the thousands of other species that also share that habitat.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And this is what Miguel, and other scientists, and conservationists have been trying to do for many years. Along with conservation organizations in southern California, Miguel has been campaigning to save California mountain lions by building a massive wildlife crossing. A wildlife crossing could be a tunnel or a bridge dedicated exclusively for wildlife so they can safely cross human-made barriers like freeways. And because urban development cuts through so much of California’s landscape, a wildlife crossing is a big step to help stitch back this fragmented ecosystem. It’ll create a safe passage through heavily trafficked parts of Los Angeles leading to vast open spaces to the north, significantly expanding wildlife habitat beyond these urban areas, which is why this wildlife crossing is so critical. And you know what? The Los Angeles constituency agreed the wildlife crossing campaign was a huge success.

Miguel Ordeñana:

And I think this bridge is unique because it’s going to be the biggest wildlife crossing ever built.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Like the biggest in the world. But a construction project of this scale also comes with a huge price tag, a hundred million dollars.

Miguel Ordeñana:

It’s also being built in the most urban setting in a very, very famous location, it’s in Los Angeles, and people know where that is.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Once completed, this crossing will be a very prominent visual landmark that’s hard to miss. I mean, picture a giant bridge above the 101 freeway in Los Angeles, one of the busiest highways in the world. And unlike a traditional freeway overpass, this bridge will be covered in nearly one acre of native vegetation. It’ll be a green wilderness area floating on top of 10 lanes of freeway, and it’s going to provide all kinds of wildlife from mountain lions to bobcats, lizards, and even low-flying birds with the shelter, food and water they need to survive. And for the mountain lions, this means they’ll be able to travel safely to new territories to mate, which will help prevent any mountain lions in the future from being stuck alone in an urban park their entire life, or from meeting the same fate as P-81, born with a kinked tail and killed in a vehicle collision along the highway.

Miguel Ordeñana:

What’s big about this is, not too long ago, people really discounted urban areas as places for conservation period, whether it’s for protecting mountain lions or any other species. But now all of a sudden, this place that’s known for movie stars, traffic, of course, smog, et cetera, is now known as a really important location for wildlife conservation. When you raise a hundred million dollars to build a crossing to basically right some wrongs that the human population committed by cutting these mountain ranges in half with freeways, and now we’re literally paying the price, a very expensive price, but it’s the least we can do because we’re not giving up on our wildlife.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

It really is the least we can do, I mean, there’s no doubt that this wildlife crossing is a huge win for conservation. But if we’re going to undo the damage that we’ve inflicted on these native habitats along the California coast, one wildlife crossing, even if it is the biggest in the world, isn’t enough.

Miguel Ordeñana:

We’re putting this massive bridge, investing in this huge connector, and that it, hopefully, acts as not only a bridge for these animals but a bridge for communities historically excluded from conservation work and the conservation movement.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

On top of being a wildlife biologist, Miguel is also the community science manager at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, and he’s doing the work of bridging communities within his own institution.

Miguel Ordeñana:

You have to realize that this institution here, for example, has been around for over 100 years, and there are communities within a mile of this museum who’ve never stepped foot inside because of that lack of trust.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And Miguel really understands where this lack of trust is coming from because, as a Latino scientist working in academia, he’s familiar with feeling othered.

Miguel Ordeñana:

Although I will never understand what it is like to be an Indigenous person, I do know how it feels to feel voiceless and feel excluded from conversations being disrespected.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

If you’re a listener to this podcast, unfortunately, none of this is news to you. Historically, Black and brown people have been excluded from many stem fields. Latinx people make up just 8% of the people doing science, technology, engineering, or math. And so it’s no surprise that throughout his career, Miguel often felt out of place being the only or one of the few Latinos in the room.

Miguel Ordeñana:

And so as a member of one of these historically excluded communities, even though very different community, having that perspective hopefully allows me to be a bridge, which is ultimately my goal.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So building these bridges with different communities is a big part of Miguel’s conservation work. And for some communities, this is the first time they’ve been invited to the table.

Miguel Ordeñana:

Indigenous communities have been historically excluded from conversations about wildlife management and whether it’s the permitting process, how to manage wildlife that are still living, how to study animals, how to incorporate indigenous science into ongoing research and management of animals and their habitat.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And we see how the exclusion of indigenous communities from these conversations creates gaps in communication and can lead to real misunderstandings.

Desiree Martinez:

This past year, we just found out that there’s actually a law that’s in place that determines how mountain lions in particular are tracked, studied, and in the end, disposed of when they die. And at no time when that law was being contemplated, was there any tribal consultation?

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And this law dictates that when study animals like P-81 for instance die, their remains are to be cremated, which doesn’t align with the tribal tradition that aims to give departed relatives, humans, or animals, a proper burial ceremony. And remember what Desiree mentioned earlier.

Desiree Martinez:

All of the other mountain lions that have passed, we did not do a ceremony for them. We don’t even know who they are.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

This is because there isn’t an official protocol to inform tribal communities when a study animal has died, so they don’t get a chance to give a proper burial or even just have a voice in deciding what to do with the remains. Well, at least not yet, because giving local and indigenous communities a voice and having them be part of these conversations is exactly what Miguel is striving for. For Miguel, including indigenous perspectives in his conservation work is a continuous learning process. And as we’ve seen, the lack of trust that indigenous communities hold toward colonial institutions shows up despite the best of intentions, which is unfortunately what happened when Miguel applied for that permit without consulting the local tribes because based on the historical track record, the tribes could only assume the worst.

Miguel Ordeñana:

They see, okay, this is kind of triggering because you are treating my relative just like you treated my own human ancestors by putting them in your collection, putting a tag on them and a label, and dehumanizing them. So I think that’s an important perspective to consider, and I think it’s a perspective that for many years has been just pushed under the rug or discredited or ignored.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But starting up these conversations to have more indigenous involvement in conservation is a slow process.

Desiree Martinez:

As with anything, it’s always about capacity. We just don’t have the capacity within our communities to do it. Everybody has the day job and people have taken on leadership positions in the tribe as a second job. And so there’s only so much time and energy in order to do that.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And Miguel is very much aware of this lack of capacity and the uphill battle that he’s in for.

Miguel Ordeñana:

We have 35 million specimens here in our collections, from insects to lizards to mammals, you name it, and they’re all significant. But for us to consult with them every single time we collect a specimen is not a sustainable thing. We need to figure out a way that is manageable for the museums to be able to incorporate into their policies and procedures, but how do we curate our collection or go about collecting in a more culturally sensitive way? And so no matter how awkward and how much I’m seeming like a squeaky wheel, I am very committed to getting people to listen, and to start acting more respectfully, and to do science differently, to do wildlife management differently.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Bringing cultural sensitivity into academic and other historically colonial institutions is a start, the first step for reducing harm. But doing this work is not just beneficial to indigenous tribes and other marginalized communities. If we learn anything from the colonial history that’s shaped California’s landscape, both culturally and literally, there are real problems and the way we’ve been socialized to view nature. But there’s another way of looking at the world that could save not only mountain lions from extinction but all of us.

Desiree Martinez:

One of the big things in terms of thinking about Tongva traditional values is seeing each other as being humans. I’m talking about what the general public considers are resources. So the water, the air, the Animals, the plants, the ground, those we consider our relatives. And because our relatives can’t speak for themselves, we have the responsibility to speak on their behalf to make sure that they can survive on the land.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Seeing the humanity in all living things, this is what colonialism refuses to do.

Desiree Martinez:

From the very beginning, when European settlers came to our lands, they didn’t see us as human. They saw us as something other than. We were animals. We were something to be tamed or in controlled. And we always come to the premise that we are all human beings and we should all be treated as such. And so part of that is also teaching the general public that not only do we have a responsibility as indigenous people because this is our land, but now that they live on our land. And our settlers, they also have that responsibility.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Exactly. We all live and work and struggle and thrive on this land, and it’s our responsibility, all of us, to be stewards of the land too. And what that looks like in practice is collaboration because indigenous communities couldn’t and shouldn’t do this work alone.

Desiree Martinez:

It takes a lot, including financial resources, in order to manage lands. So even if, for instance, we were to get all of the Santa Monica Mountains given back to us, we wouldn’t be able to manage it. I mean, particularly here in Southern California, there’s always the fire threat. So any land that’s wild, you’re going to need some type of fire prevention, and we don’t have the knowledge on how to do that, and so there’s no way that we’re going to be able to take thousands and thousands of acres back. We just don’t have that capacity, new tribe does. But that doesn’t mean that there can’t be collaborative relationships with tribes. So that’s when you start to partner and become co-stewards, co-stewardship of the lands with the goals of making sure that those animals and plants that are on the lands continue to survive.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And one of the best ways to achieve true collaborative relationships is not just by giving indigenous communities a seat at the table, but also ensuring that there are indigenous peoples in leadership positions within these historically white institutions, visionaries who can guide us to a better way of looking at the world because to truly save our environment on top of building connective structures to unite our landscape back together, we also need to unite ourselves back together with nature so that when we talk about sustainability, it’s not just sustainability for us at the expense of other species, the land, and other things we think of as resources because the truth is there’s really no way to make our insatiable need for growth and urban development sustainable. These resources are dwindling and continuing in this direction will have ripple effects that will impact ecosystems far and wide.

Desiree Martinez:

I like to think about us as being that story about the bird in the mine. We are the ones that are bringing up and warning about what could happen to the people, that our history is reflective of what people can do to other people, that it was very easy to take our land, it was very easy to take our water. Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it. We have lived through that history. We all need to work together to make sure that we do everything possible in order to ensure our survival here on this land.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And Desiree’s right, it’s our survival that’s on the line here. On our next episode, we’ll find out just how much we have to work together and find solutions by conserving the health of our most precious resource, water. We would like to take a moment to acknowledge that the Los Angeles, California area, the locations where the stories from this episode took place. California was densely populated in pre-contact times. Every mountain, every field, every region was inhabited. The California indigenous were everywhere. Los Angeles in particular is the homeland of the Chumash Tonga and Fernandeño Tataviam peoples, they were, and still are, the caretakers of the land on which they live. The indigenous peoples of the area were noted for their peaceful traditions and for harvesting the bounty of the land. Their connection to the natural environment was so intimate. Some even called it eloquent. For example, the Tongva people referred to the abundant vegetation of their domain as the plant people. They had elaborate protocols for the handling of plants used for medicinal and other purposes.

The Chumash people have lived in the Los Angeles area since time immemorial, the California coast has been home to indigenous peoples, including the Chumash for at least 11,000 years. By intentional burning of certain parts of the landscape, the Chumash people transformed the region into one of the most resource-abundant areas on earth. The Tongva, also known as the Gabrieleño, was considered one of the most culturally sophisticated societies upon European contact. All good land acknowledgments must reference the past, present, and future. That said, the 19th-century past of indigenous California is ghastly. With the American annexation of California in 1848, outright genocide prevailed for decades. Within two years of the Gold Rush of 1848, 100,000 indigenous people were exterminated by the gold seekers from a population of 150,000 at the beginning of the Gold Rush, less than 30,000 indigenous people were still alive 10 years later. The state’s first elected governor, Peter Burnett, openly called for the genocide of the state’s native population. The extermination continued unabated until 1873. It has been termed the worst genocide in American history.

Today, Los Angeles has a large urban indigenous population of over 50,000 composed mostly of peoples who originated outside the state and many from Latin America. The native people continue their struggle for land reclamation and the end of discrimination. There are many indigenous organizations in Los Angeles working in the interests and needs of the native people. Contact can be made for information for those who want to assist in much-needed cross-cultural understanding.