Speaker 1:

Hurricane Earl drenched Belize on Wednesday night, packing winds of obscene-

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

In 2016, Hurricane Earl had devastated Belize.

Speaker 2:

We’re speaking about major structural damage-

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Just hours after the storm, National Geographic Explorer Jamal Galves got a call to go rescue a manatee.

Jamal Galves:

We started making our way to the city and the way I could have seen disaster, light poles down, trees broken, leaves everywhere, cars underwater, roofs on the road. There’s a huge boat in the middle of the highway.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And that’s when he saw a baby manatee in the parking lot of a motel.

Jamal Galves:

I’ve never dealt with a manatee that small before, so I looked at it, checked it out, and I realized it still had its umbilical cord attached. So that tells me it could not have been more than one or two days old, a newborn calf, and it’s just panicking, flapping around, probably wondering where is its mommy, scared out of its mind. The first exposure you get to life is this.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

I’m Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant, and this is a different kind of nature show, a podcast all about the human drama of saving animals. This season we’re going to take a journey through the ecological web, from the tiniest of life forms to apex predators. We’ll hear stories from scientists, activists, and adventurers as they find all the different ways the natural world is interconnected, and together, we’ll explore our place in nature. This is Going Wild.

If you find yourself needing a transcript, we’ve got one in the episode show notes.

Jamal Galves:

You’d be surprised how excited I get every time I see a manatee.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

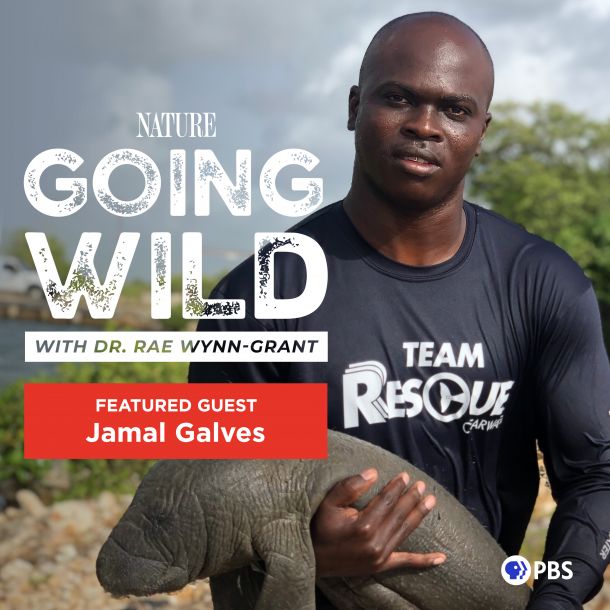

This is Jamal Galves. He’s the Program Director at the Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute in Belize, and he’s been working on manatee conservation since 1998. To say that he loves his job would be a huge understatement.

Jamal Galves:

It’s kind of embarrassing actually. When I’m out with people or out with kids specifically and I see a manatee, I go, “Hey, manatee, manatee!” And then I have to catch myself and compose and act all professional, like, “Oh, this is normal.” You know?

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

If you haven’t seen a manatee before, they’re very charismatic animals. They look a little bit like a walrus, but they don’t have any tusks, and they have these big, brown nostrils, so when they come up to the surface to breathe, you could mistake one of them for a floating bowling ball with whiskers.

Jamal Galves:

They are also referred to as sea potatoes because they’re kind of big, they eat a lot, so they tend to be chunky, but they’re generally slow-moving, docile, gentle, caring, cute creatures.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

I’ve worked with all kinds of animals in my career, from African lions and primates to North American bears and cougars, but Jamal has been laser-focused on one species ever since he was 11 years old, and with good reason. While I was reading about bears and lions in books and watching them on nature shows, Jamal was already getting up close and personal with the mammals that would become his life’s work. He was born in a small village of about 300 people right on the Belizean coast named Gales Point Manatee.

Jamal Galves:

Ironically named after the species, or are the species named after the village? But I believe it’s the other way around.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal says that his hometown got its name because it has one of the highest populations of Antillean manatees in the region.

Jamal Galves:

You can be swimming and you can have one that is coming close to you because they’re curious. In Belize, we refer to that as interfering. In America, I think it’s nosy, so these animals are very nosy. They hear something, they want to come check it out to see what it is.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Aside from being generally adorable, manatees are a vital part of a local ecosystem. They’re the largest herbivores in the sea, weighing in at an average of 1,200 pounds, and they eat roughly 10% of their body weight in sea grass and aquatic plants every single day. That’s a lot of greens. As well as keeping the waterways clear, they create literally tons of nutrient-packed waste, which small fish rely on for food.

Jamal Galves:

And small fishes and crustaceans are eaten by big fishes and we eat big fishes. So in other words, we’ve all had a little bit of manatee poop at some point in our life, but I don’t see anybody complaining. It makes you realize how important they are.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Thanks to Jamal’s work and the residents of Gales Point, the manatees living there are relatively protected, but the species in general are in terrible danger and their survival’s uncertain. Boat collisions, climate change, development, and habitat loss have all contributed to the crisis. Today, there are less than a thousand Antillean manatees left in Belize, and Jamal says that if we don’t act now, their disappearance will leave a devastating gap in the ecosystem, not to mention the loss in his community who’ve been stewards of the area for centuries.

Jamal Galves:

The species is really entwined in our entire life in that community. I think it’s in our DNA that you are born to know that you shouldn’t harm manatees. They are part of our family, so it’s kind of like you look after the people that you care about the most.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And it’s not just manatees that make the neighborhood so unique. Jamal and the people of Gales Point have a deep understanding of why preservation is important. It’s truly part of their history.

Jamal Galves:

Gales Point Malanti is the last, last Maroon Creole village alive that still practices our culture, still practices our food, our language as much as we do.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Gales Point is a Belizean village with strong ancestral roots. It’s one of several communities that were founded by formerly enslaved Africans in the 1700s. These men and women escaped British plantations and fled to remote parts of the country where they established their own communities and reclaimed their freedom. In these Creole villages, they felt safe to practice the West African language and traditions that they maintained despite their experiences with chattel slavery. Most of these historic places have long since disappeared or been consumed by the surrounding culture, but not Gales Point.

Jamal Galves:

So we are unique and I’m proud to be a part of that, proud to promote that. I’m proud to talk about that. I’m proud to see that I grew up there despite the fact that on the outside, it’s seen as just this poor village, our people there are happy. We don’t have economic value, we don’t have opportunities with jobs and ways of making income, but we are rich in our environment. We are rich in our surroundings, and rich in our people and our culture.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Now, you might think that growing up surrounded by manatees in a village that is literally named after the species, Jamal would’ve been fascinated by these animals from day one, but actually, his path to protecting them all began because of a strange boat.

Jamal was just 11 years old when he first spotted it, cruising past his grandmother’s lawn.

Jamal Galves:

I’ve grown up around boats my entire life and I’ve never seen a boat with an engine in the front.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

The boat said, “Manatee Rescue” on the side. Now, it had a tower on the top that could be removed, and the back of the boat came right off the body, but without making it sink. To Jamal, it looked like a giant transformer, one of those toys that turned from a car or boat into a robot.

Jamal Galves:

I would walk along the roadside to follow the boat as it gets out of my eyesight just to try and keep up with what they’re doing and where they are. So I spent a lot of time looking at them from the shoreline, just imagining, just hoping that one day I can actually get out there.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Eventually, Jamal gathered up his courage and went down to the water to meet the crew.

Jamal Galves:

At that point, these weren’t even my interests. It’s just being the first kid from the village to be on that boat.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

This is where he first saw the man who had become his mentor, Dr. James “Buddy” Powell, an American marine scientist and one of the foremost manatee researchers in the world.

Jamal Galves:

He’s just sitting there with his dark glasses and his usual glass of coffee, getting ready to go underwater, and this little kid, small, skinny, I didn’t even have on a shirt, no footwear, so that shows you how ready I was. I was ready to be in the water.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

There is actually video footage of Jamal at around this time. He’s wearing nothing but a pair of shorts, standing in knee-deep water next to the boat, and his face is totally serious. He’s laser-focused and so small.

Jamal Galves:

I walked up to him and I said, “I want to come out with you guys.” That was the first word I said, not even, “Hi. My name is…” Like, “No, I want to come out with you guys.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal’s bravery here is just incredible to me, not only because of his age, but also because he was a young Black kid from a tiny little village in Belize, the descendant of enslaved Africans who fought their way to freedom, and he was demanding attention from a group of internationally renowned scientists. I can tell you from experience that even as an adult, this situation would be intimidating, but 11-year-old Jamal was unfazed by their status. He wanted to get on that boat.

Dr. Powell looked at this scrawny kid for a moment or two and then finally shook his head, “Kid, you’re too small.”

Jamal Galves:

And I was very, very, very disappointed. I was upset, I was furious, I was discouraged, and I expressed that on my face because I’m really good at making an I’m-about-to-cry face.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal’s face must have been pretty convincing because Dr. Powell relented and then Jamal set out on his very first manatee expedition.

Jamal Galves:

I went out on the boat that day without even asking my grandma’s permission, which had some consequences when I got back home, but that story is not for today.

Being out there with these world-renowned scientists made me feel so important. Coming from where I’m from, you don’t normally get those types of experiences. So for me, it was fascinating being out there.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal had never seen a manatee out of the water before, but the team didn’t treat him like a little kid. They let him get right in on the action.

Jamal Galves:

To see them touching these animals, bringing them on boat, and literally performing a health procedure, like when you go to the hospital, they take your weight, they take your measurement, they take your blood, medication is administered if they need to, and I’m just like, as a kid, just trying to soak all this up. My brain is just expanding, taking in every single thing, memorizing the entire process.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

After a few dizzying hours of watching the scientists at work, Jamal saw the team haul a new manatee up onto the boat.

Jamal Galves:

And I go, “That doesn’t look right.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

As they pulled the animal onto the scale, Jamal’s stomach dropped. The manatee was covered in so much scar tissue that it looked like someone had gotten a marker and scribbled all over its body. There were deep scratches and gouges everywhere he looked.

Jamal Galves:

I’m seeing this scar after it’s healed. Imagine seeing it when it was just happened. And I started asking questions.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

The crew told Jamal that manatees get hit by boats all the time. In fact, boating accidents are still one of the main reasons they’re endangered. Boat drivers usually aren’t careful and they’re encroaching further and further into manatee habitat, and as tourism in the area increases, the problem has only been getting worse.

Jamal Galves:

I couldn’t understand why would somebody hit a manatee with a boat? And I stood there puzzled in my own world. My mind’s not even on that boat anymore.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And that’s when Jamal made a decision that would change the course of his life.

Jamal Galves:

Oftentimes, you see in the news or you hear if an animal or a species is in trouble and you all sit back and feel things of sadness, but think to yourself, “Somebody’s going to do something about it.” That’s the biggest mistake in species extinction because somebody is nobody, and I wasn’t going to wait for nobody to show up because we thought somebody was going to appear.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And so at just 11 years old, sitting on a boat surrounded by a team of international scientists, Jamal made a promise. He was going to dedicate his life to saving the manatees that were so intertwined with his home and his culture, and so what if they were 10-times his size and he was still in grade school?

Jamal Galves:

I’m not sure if I was so fascinated that I could not sleep or was it because I was afraid that if I overslept, they’ll leave me the next day?

I’m in the shower. My grandma’s room is next door and she goes, “Who’s in the shower at four o’clock in the morning?” I was like, “Me, grandma.” And she’s like, “What are you doing?” I’m like, “I’m going to go help manatee research.” And she’s like, “Boy, they don’t leave until eight or nine o’clock. Go to your bed.”

And so I went back to my bed, lied there, and just basically I was looking at the clock, literally hearing every second that that clock go, “Tick, tick, tick, tick, tick.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal arrived at the boat at 6:30 AM. Dr. Powell was sitting on the dock drinking his coffee just like the day before. The rest of the crew hadn’t even arrived, but Jamal got straight to work.

Jamal Galves:

I started loading these bins of equipment onto the boat and he just sits there looking at me, probably wondering, “What the heck is this kid doing?”

Being out there that day, I memorized everything from the day before. So before the vet could have said, “Pass me the medical kit,” I already had it in my hand. Before they could have said, “Get me the tape measure,” it’s in my hand. Before they could have said, “Bucket for water,” hey, I’ve got the bucket and I had got the water. I was just doing everything to be a part of this team.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And when the team got in the water to capture a manatee, Jamal jumped right in there with them, but he couldn’t have been more than 70 pounds soaking wet. Dr. Powell saw this skinny little kid jumping in the water with his team and a 1,200-pound manatee

Jamal Galves:

And he goes, “Kid! Kid! Get out of there, out of there!” I’m like, “This guy’s embarrassing me in front of all of these people.” So I get up on the boat. I’m very, very steamed and embarrassed, and he goes, “Kid, just stay on the boat. You’re going to have your chance. You can be my assistant. Stay on the boat, don’t go in the water. You’re too small.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And it wasn’t long before Jamal would get his chance. As luck would have it, one of his friends began working as a caretaker at the Manatee Rehab Center. One day, they needed help in the pen. Jamal was beside himself with excitement. Slowly, he lowered himself into the enclosure with a teenage manatee named Hercules.

Jamal Galves:

I’m standing in the water. I could see the silhouette from its body coming straight towards me.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Now, it’s one thing to meet a manatee on a boat surrounded by scientists and quite another to meet a juvenile manatee in its own environment. Jamal was suddenly not quite as confident as he had been with the team.

Jamal Galves:

My heart is pounding. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. Is he going to bite me? Is he going to… At this point, I didn’t know what he was going to do, so I was frantic. I’m just standing there, not even breathing.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Before the break, 11-year-old Jamal Galves was climbing into a pen with a young manatee named Hercules, and now standing alone in chest-high water, young Jamal’s lost his nerve. He’s absolutely terrified.

Jamal Galves:

And my heart is pounding. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. I could see the silhouette from its body coming straight towards me.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But then something amazing happened.

Jamal Galves:

He comes up to me, he puts his head on my chest area, takes his flipper, put it around me like he’s holding me, almost as if I’m giving you a hug.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

In that moment, Jamal was overwhelmed with a certainty that this animal, this being was communicating with him.

Jamal Galves:

And to me, that’s something that is larger than any payday, any promotion, any recognition, that manatees have already served. They’ve already given me my token for my work. No matter how much I do now, it’s already paid for. The feeling of gratitude expressed from an unspoken being is priceless. Unexplainable.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

After that first summer was over, Buddy Powell and his team left Gales Point to continue their work elsewhere, but Jamal stayed behind along with the manatees, and it occurred to him that the manatees weren’t the only ones whose destiny was uncertain.

Jamal Galves:

People don’t become scientists and researchers, and where I come from, I grew up in poverty. I grew up exposed to guns, drugs. Society has already written our destination basically, and it’s ingrained in people’s life that they literally, in their mind, believe that they can’t be more than just what society expects of them.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Unfortunately, the kind of inclusion that Jamal experienced is quite rare in wildlife conservation, particularly back in the ’90s. And that’s not just because Jamal was so young. Foreign teams of scientists would fly into the field and they often wouldn’t include local people in their research, so the people on the ground are left on the outside looking in no matter how valuable their perspective and participation could be. But the Clearwater Marine Aquarium was different. Although Dr. Powell was white, he hired local adults to work with the manatees too. So when the researchers returned the next year, you better believe Jamal was waiting for them.

Jamal Galves:

What kept me coming back is because every year they taught me something new. I went from taking measurements to writing down notes, to eventually doing stuff like taking blood, doing more things that people that look like me should not be doing, but they exposed me to that. They brought that opportunity to me. They’ve seen my dedication.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal volunteered all the way through school and eventually, after several years of assisting, he landed a full-time position with the research team, but he soon realized there was a limit to the effect he could have from the deck of the boat. For manatees at Gales Point and all over the world to stand a chance, policies needed to change, new rehab centers needed to open, and protections needed to be put in place at a governmental level.

Jamal Galves:

I had this vast amount of knowledge because I’ve been learning about the species since I was 11 years old, but nobody in higher offices listened to me, paid attention to me, or they disregarded me very quickly because one, I’m Black, two, I have no degree.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Being a young Black man without a degree should not be the reason people in power didn’t take him seriously. Racism and elitism are two powerful forces that are preventing some of the most important change our world needs, and too often, locals are relegated to support and caretaking roles and are rarely in leadership. Jamal understood that and taking pride in his racial identity, he decided to do something about that lack of a college degree.

Jamal enrolled at a prestigious junior college in Belize City, then moved on to the national university for his bachelor’s. He worked his way through both programs, cycling to and from school to work, spending every spare moment he could working with the animals he was studying so hard to save. And then with the encouragement of the team at the Marine Institute, he was offered a scholarship to UC Santa Cruz for his master’s in Coastal Science and Policy.

But for Jamal, it’s not about the master’s degree itself; it’s about what it allows him to do for his community. All of that hard work means that Jamal can now advocate for manatees in those meeting rooms that have been historically reserved for foreign scientists. And today, that tenacious kid from Gales Point Manatee is working all over the world with organizations like National Geographic advocating for these animals and the village they call home.

Jamal Galves:

In the science world, you want to refer to them as F105 or FM102, but we give them names, names that dictate their personality, names that identify them because they’re not a number in a computer and an Excel sheet. They are living beings that are being impacted, that have feeling, that have emotions. They have different ways of expressing it, but they feel, see, love just like we humans do.

I mean, some manatees like coconut peel, but some like apple. Some manatees take comfort in sucking on your knees, and that feels horrible because they have these bristles on their mouth. Some manatees do barrel rolls, while some sleep all day. It really, really, really varies in terms of who they are, that they literally have their own specific identity.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Though every manatee is unique and special. There’s one in particular who’s fought her way into the hearts of Belizeans all over the country, but sadly, it wasn’t her character that caught the public’s attention. It was instead her part in a tragedy that would tear apart the lives of tens of thousands of people across Latin America and the Caribbean.

Jamal Galves:

Every year, we have a hurricane season from June to November. Anytime within those months, we can get a hurricane, but it’s the reality in which we live in the Caribbean here.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

To begin with, hurricane season in 2016 was just like all the others. Forecasters on the news were following threats and making predictions, but Jamal and his family weren’t too worried.

Jamal Galves:

There’s this guy on the news that we call Chief.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Belize’s famous media personality, Chief, hadn’t yet sounded the alarm.

Jamal Galves:

People will be like, “Is Chief on the news yet? No? Okay, call me when Chief is on the news,” and when you see Chief on there, you’ll know it’s time to board your windows up and start securing stuff, go to the grocery store to get what you need to get because it’s going to be wild.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So Jamal and his family were going about their business with one eye on the weather channel waiting to see if Chief would show up.

Speaker 3:

We’re out here at around 9:30 at this time.

Jamal Galves:

They’re giving us forecasts on the news.

Speaker 4:

27 shelters in Belize-

Jamal Galves:

They’re putting up the flags, the hurricane watch, and then boom.

Speaker 5:

In the next couple of minutes from now-

Jamal Galves:

The hurricane is coming into Belize.

Speaker 5:

… It should be making landfall. We’re just waiting for that confirmation. Once it makes landfall-

Jamal Galves:

You can hear the trees whistling, the rain slamming against the house. You could hear those dinks on the roof, fluttering as it was going to come off.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

When Hurricane Earl came tearing from the Caribbean Sea into Jamal’s neighborhood, it was a category one hurricane with sustained winds of over 80 miles per hour, strong enough to uproot trees, pull mobile homes from the ground, and tear the roof right off Jamal’s house.

Jamal Galves:

And I could have plainly hear that roof just banging. I’m just sitting in there just hoping, praying, “Don’t take this roof off” because we’re inside, there are kids, my mother, brothers and sisters.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

The storm raged in Belize City for nine hours causing tidal surges of seven feet, damage to buildings, roads, flooding homes. But Jamal and his family were lucky. When the storm finally moved north of Belize City, their roof and Jamal’s home were still intact.

Jamal Galves:

We lost power. We lost water. So it’s basically the radio and they’re listening to Chief, and you’re just waiting for Chief to tell you, “Okay, it’s okay to go outside.”

When the hurricane passed, I put on my phone to see if it had service or internet, and boom, my phone ring. “I have a baby manatee for you.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

The stranger on the other end of the line told Jamal he’d found a baby manatee on his property. Now, Jamal gets rescue calls for manatees all the time, and most of them don’t turn out to be manatees at all. Sometimes it’s just trash floating in the mangroves or a different wounded animal in need of help. So when the caller told Jamal where he’d found the manatee, Jamal thought, “Impossible.” Manatees hardly ever get washed ashore in storms in Belize, and it wasn’t anywhere near the water, but the guy insisted.

Jamal Galves:

“Yes, it’s here in the backyard.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

As Jamal drove through Belize City, he could barely believe his eyes.

Jamal Galves:

Light poles down, trees broken, leaves everywhere, cars underwater, roofs on the road. People’s houses were damaged, and as I make my way closer to the city, there’s a huge boat in the middle of the highway.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

When Jamal got to the caller’s property, he found the youngest manatee he’d ever seen lying in a puddle in the backyard.

Jamal Galves:

I’ve never dealt with a manatee that small before. So I looked at it, checked it out, and I realized it still had his umbilical cord attached. So that tells me it could not have been more than one or two days old, like a newborn calf.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Not only that, they were nowhere near the water. That meant that this tiny creature, in its first hours of life, had been ripped from its mother by a tidal surge, washed across a marina over a major highway and into the backyard of a motel.

Jamal Galves:

And it’s just panicking, flapping around, probably wondering where is its mommy, scared out of its mind.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal could not understand how this manatee had survived.

Jamal Galves:

We’re inside our homes, and we were afraid and worried. Now, imagine that young calf, not just out there, out there alone in something that she’d never experienced. She could have probably hear those trees whistling all over the place, debris flying, rain coming down hard on her. In the dark, she’s out there vocalizing, calling for her mama. Mama is probably in the ocean and frantic thinking, “I lost my baby.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal stepped into the water and lifted the baby manatee up to his chest.

Jamal Galves:

I could have felt the blood pumping in her heart really fast. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. I had never felt or seen a manatee heart beat that fast. So I clutched her up to my body to sort of make her feel safe, and I could clearly feel the boom, boom, boom starts to slow down. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

From that moment on, the clock was ticking. Jamal knew that time was running out to save the baby manatee. If she stood any chance of survival at all, she had to get to the rehab center immediately.

Jamal Galves:

We hop in the truck and we took off, and I noticed a weird behavior on the way.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

As they drove through the wreckage of Hurricane Earl, the manatee calf in Jamal’s arms kept pushing her head back away from her body and she was struggling to gulp down air. Manatees are mammals, so even though they live in the water, they need air to breathe. Baby manatees will ride on their mother’s backs and practice what it feels like to come to the surface, take a breath, and dive back down into the water.

Jamal Galves:

And then I realize that she doesn’t know that she’s out of water. She doesn’t know the differentiation. She’s taking her head out, trying to feel for that transition between water and air, and because she’s not feeling it, she’s not opening her nostril to breathe.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

This little calf had been taken from her mother so young that she’d missed a vital step in her early development, and if Jamal didn’t do something about it soon, she was going to die right there in his arms, suffocating herself on dry land.

Jamal Galves:

I was like, “Turn around right now.” I rush into a grocery store. I bought a small blow-up pool. We quickly fill it with water and put it in there, and she quickly just starts to breathe on her own. She’s like, “Okay, I’m okay now.”

On the way to the rehabilitation center, it’s quiet because you want to keep her quiet, comfortable, and you could hear her vocalizing. I don’t speak manatee, but I’m pretty sure she’s probably calling out for her mom like, “Mommy, mommy, where are you? Where are you?”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Sitting in the back of the truck with that tiny manatee listening to her call out for a mother she would never find, Jamal felt helpless.

Jamal Galves:

No matter how much conservation action you’ve done, no matter how much you donate, no matter what you say, no matter how much you express love and care for species like this, you cannot replace what we’ve taken away from these animals, what we’ve taken away from that young calf. Our actions that have caused disasters to be more frequent and more stronger are responsible for that.

Now we have this young calf cheated out of her childhood with her mother, cheated of being able to be taught where to go and how to behave, and cheated of spending that most important time with its mother. It’s gone and now left in the human care, and I know I would do my best to make her as comfortable as possible, but it doesn’t even measure up at all.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Finally, they pulled into the rehab center and Jamal handed the baby over to the team.

Jamal Galves:

She’s so young that we didn’t know if she was going to make it through the night. So at that point, we were just fingers crossed, hoping. I left her there with the rehab crew and checking every hour, checking every end of the day. And I heard that she’s progressing, she’s starting to feed, she’s getting more comfortable. And as I heard that, I just felt this sense of peace.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

When the time came to give this manatee calf a name, Jamal didn’t even have to think about it. He knew exactly what to call her.

Jamal Galves:

I gave her the name Hope because from all that disaster is one positive thing that happened that made me feel hope, that if you could have gone through this and survive and fight through this, we can fight too, anything that challenges us.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Before long, the local news got involved and Hope the Manatee’s story was broadcast all across the country. She became a symbol of hope, not just for Jamal, but for everyone whose lives were devastated by Hurricane Earl.

Jamal Galves:

It’s hard to start over when you’re in a developing country like Belize, but just knowing that that one little manatee survived that makes you feel that you know what? I can build back home. I can build back home.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

There’s a quote by an author named Frank Warren that Jamal likes to use when he talks about the manatees. It says, “It’s the children the world almost breaks who grow up to save it.”

Jamal Galves:

And I refer to Hope as that, but I also am referring to myself. Where I grew up, I could have been a gang member. I could have gone to jail, I could have been in prison, I could have been dead, but my focus was so much on the manatees that they kept me away from all of those negative things. So you can’t pay me to do this. It’s what I want to do. If I had another job, I do it for free because this is my token of thank you to them, to the planet.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Now Jamal is a National Geographic Explorer using his experience with manatee conservation to change the future of not just the manatees themselves, but the people in the Gales Point community where he grew up. Back in the ’90s when Jamal first started volunteering on the boat, there were just a handful of local people involved, but now at the Clearwater Marine Aquarium where he works as program director, 60% of the research team is made up of Gales Point residents.

Jamal Galves:

Being on the outside for years gives me a better understanding and appreciation for being on the inside, and it teaches me to ensure that inclusivity is important and I never forget to turn back and pull someone else up because conservation is not a place for competitiveness. It’s a place that you need every single person. So knowledge is key, and sharing the knowledge is the most valuable thing.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Jamal and all of the researchers that come to Gales Point work hand in hand with the local community, and they understand that without the knowledge and experience of the people on the ground, true conservation isn’t possible.

Jamal Galves:

You can go study and get your PhD or whatever it is that you choose to get, but that’s just theory. Things in the world will not happen theoretically. It happens practically. So that man in his small little dinghy boat that sits out there for hours a day, he’s the one that can tell you how much boats actually are coming in and out of this place. He’s the one that can tell you what are the things that are threatening the system, but we don’t tend to appreciate, in general, those people.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And it’s not just about manatee protection. Jamal says that the scientific community has so much more to learn from the residents of Gales Point and all of the people around the world whose knowledge and perspective has been shut out of the ecology conversation for centuries.

Jamal Galves:

To really appreciate the idea of conservation, you have to know where it came from. In poverty, conservation is the way of life. You don’t turn off the light switch because, “Oh, I’m trying to protect the environment.” You turn off the light switch because you can’t afford to pay a high light bill. You don’t have that bucket overfilling with water because you’re, “Oh, I’m being a conservationist, let’s turn it off.” It’s because you can’t afford to pay that water bill. So to me, conservation is a poor man’s theory broadcast by a rich man.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Tourism is increasing in Belize and the battle to save the Antillean manatee continues. Jamal is currently developing plans for a new marine rescue center and training facility, and he’s working with the Ministry of Tourism to minimize the impact of development on the local waterways that are essential for manatee survival. On top of all of this and his continuing work with the Clearwater Aquarium and National Geographic, Jamal is writing a children’s book.

Jamal Galves:

Currently, it’s called A Tale of Hope, but it may change, but it’s really a book that’s going to inspire kids, not just to be a part of conservation, not just to be passionate about the world, but to have hope in whatever it is that they dream of.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And Jamal does have hope for the future, for the manatees he’s dedicated his life to protecting, and for the millions of kids in little villages like Gales Point with big dreams of their own because if we are going to make any kind of impact on the future of our planet, it’s going to take all of us working together to make it happen.

Jamal Galves:

Conservation is not a place or a time. You don’t need to be in the Caribbean to be contributing to conservation. You don’t need to be on a boat. You don’t need to be on a beach cleaning up. These efforts are dependent on donations. If you’re able to, donate to your local NGOs that are doing something to protect the planet. Volunteer, be a part of the effort.

You’re listening to this podcast today. I’ve told that story. I ask you to tell that story to three other persons and ask that three persons to tell that story to three other persons, and before you know it, you’d be surprised the amount of people you’ve inspired to want to be a part of conservation, and that’s where hope is going to come from.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

You heard the man. Hope isn’t something we can afford to sit around and wait for; it’s something we have to create for ourselves. Volunteer, share Jamal’s incredible story. There’s so much to do, but we can make a difference. Just think of that brave 11-year-old kid and remember that none of us are too small to have a big impact on the world around us.

We would like to take a moment to acknowledge Jamal Galves’s location during the taping of this episode, the country of Belize. We acknowledge that Belize is part of the homeland of the much storied Maya people. They lived in and cultivated the abundant natural environment of Central America. The Maya built one of the greatest civilizations of the ancient world. The awesome Maya civilization covered all of what is now modern day Belize. The ancient city of Caracol is estimated to have had a population of over 140,000 inhabitants. At its height, the Maya population is thought to have numbered 1 million in the area. They built huge, abundant cities. Most of the urban metropolises were within a mere 12 miles of each other, a day’s journey in those times. The Maya still live in their Belize homeland and other parts of Central America to this day.

When the Spaniards invaded in the 16th century, the Maya were divided into three separate kingdoms. The Maya suffered a severe population decline from the Spanish conquest and European diseases, to which they had no immunity. However, they fiercely resisted the European invasion from the initial incursions in the 1500s and even into the 20th century.

Today, the three Maya ethnicities in Belize are the Yucatec, Mopan, and Q’eqchi’ Maya. Right now, the Maya Belize are in a struggle for their claims on their indigenous lands. Belize adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, which established land rights for the original peoples. But unfortunately, Belize has not followed up on its commitment to the Maya people. International and diplomatic avenues are being pursued to facilitate the acknowledgement of the Maya to the undisputed possession of their ancient homeland. Maya communities are currently working with local attorneys and support groups. They are currently in the pursuit of legal assistance to resolve their outstanding land claims.