Imagine a place that is so hot that the vapor is coming out in such intensity and quantity that it almost feels like it’s mixing with the clouds, per se. And if you’re standing on one of the large rocks near the river, you actually can start sweating because you feel the vapor so hot and strong that anything alive that falls into it boils from inside out. So not only do you need to be holding onto your life on this rock that is a little slippery and has these splashes of boiling water, but you also have all sorts of creatures, like spiders and whatnot walking around you. And if you do one wrong step, you are into boiling water.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

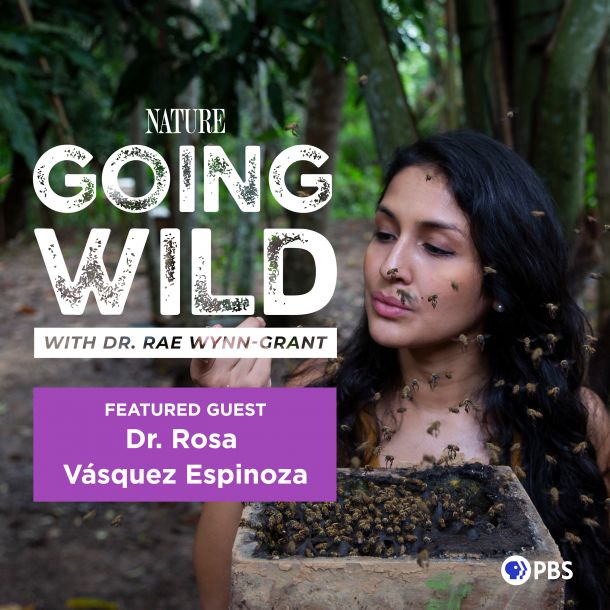

Welcome back to season three of Going Wild, a podcast about the human drama of saving animals. I’m your host, Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant. This season we’re going to take a journey through the ecological web, from the tiniest of life forms all the way to apex predators. We’ll hear stories from scientists, activists, and adventurers as they find all the different ways the natural world is interconnected, and together we’ll explore our place in the wild. This is Going Wild.

So we’re starting small, at the very bottom of the food chain, smaller than plants even, down to the bacterial level. And in order to get there…

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

This is nothing, wait until we get closer.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

The first stop of our journey is to the boiling river in Peru. A place so extreme and remote that for a long time people thought it was a myth.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Another big drop here, no. Trying to hold ourselves. I think the hardest bit was not realizing that I had boiling water below me, somehow I was okay with that. But the fact that I had all these things crawling through my hands while it was also a bit slippery.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

This is my friend Dr. Rosa Vasquez Espinoza. Rosa’s a chemical biologist, conservationist and artist. And if you can’t already tell, she’s a total badass. Right now, she’s hanging on to a slippery rock wall over the boiling river because she’s on a mission.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

The boiling river is a place like I’ve never seen before. It’s located in the central Peruvian Amazon in the heart of our jungle, and it is considered one of the largest thermal rivers in our planet.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Unlike a thermal pool or a hot spring like the ones you might find in Yellowstone, this thermal river isn’t just a standing body of hot water. It’s a four-mile-long river that flows as wide as a two lane road with water temperatures hot enough to boil a small animal if it fell in. Rosa grew up in Lima, the capital of Peru, and she spent a lot of time exploring the Amazon jungle since she was a little kid, traveling with her mom from the city into the jungle to visit her cousins.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

And we would go up and down the Amazon River to get to their communities. I would literally just spend time playing in the riverbank with them, with the water and get to play with their monkeys or whatever animals they were having at the time.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But even as a Peruvian who spent her childhood summers in the jungle, Rosa didn’t find out about the boiling river until she was in grad school getting her PhD at the University of Michigan. And from the moment she heard about this river, she was hooked. But what drew Rosa to this mythical place wasn’t just the crazy adventures or even the exotic flora of fauna. What she was most curious about were the tiny life forms that live in and around the boiling river. We’re talking about microbes.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

So microbes are virtually everywhere. They can be in the air, they can be in the soil, in water, in our skin, in our guts, in animals, plants. They are tiny microorganisms that most of the time are invisible to the naked eye.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

They really are everywhere, and they include things like viruses, fungi, bacteria.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

I think most people think in general that microbes are bad for us, can make us sick, can make our waters or ecosystem sick, but that is a very small percentage of microbes since most of them really keep everything around us and within us healthy. Microbes are what maintains the health of our ecosystems, our oceans, our mountains, our jungles, as well as our own human bodies.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Basically, microbes help balance life and as a chemical biologist, Rosa’s goal is to learn how microbes can help us. She does this by learning about the different chemicals that microbes produce, and from there she figures out how they can be used to create new biological solutions from medicines to other beneficial uses. But Rosa really has her work cut out for her because studying microbes is like studying an infinite universe.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

So there are more microbes on earth than there are stars in the galaxy, which is wild to think about. And how many of these we haven’t discovered and that we don’t know about?

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

The answer is a lot. According to a new estimate, only 1% of Earth’s microbe species have been thoroughly studied.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

That’s insane to me. Considering the large numbers that are out there.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And one big reason is because it’s actually really difficult to grow microbes in the lab.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

We don’t have the ability to provide a nice home for them to grow in the laboratory. We don’t have the food or the specific conditions. It’s always much more difficult to recreate what nature does naturally. And so that really limited our understanding of them for a very long time.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Rosa found this unacceptable because considering that antibiotics, cancer treatments and all sorts of medicines have come from that 1%. Imagine the potential that’s left in the other 99%. And we’re not just talking about medicine, there are all sorts of environmental solutions microbes can provide that we’ve barely started to explore.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Could microbes help degrade plastic or could we use microbes to be able to break down oil spills much faster than we could with other methods?

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

These new medical and bioremediation possibilities are super exciting and could literally save the planet.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Now, trying to…

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And that’s why Rosa is climbing a rock wall over the boiling river. She’s on a mission to find microbes that can help solve the world’s biggest problems, but this mission she’s on might not have happened if it weren’t for Rosa’s grandmother.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

She’s a badass.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

You could say that Rosa’s interest in the medicinal potential of microbes is in her blood passed down from her grandmother from an early age.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Whenever I was not at school, my parents were still working, and so I spent a lot of afternoons and evenings with my grandma.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Unlike Rosa, who grew up in the city, her grandmother is from a remote village in the high Andes.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

She didn’t have a chance to go to school. She was working to put her brothers and sisters through school.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

When Rosa’s grandmother was a child, instead of going to school like the rest of her siblings, she was working in the fields farming potatoes, and she was surrounded by all these elderly women. Working alongside her, they shared generations of wisdom and experience all about plants.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

She started to learn, “Oh, you plant these specific seeds in this specific way in this time of the year so that you can get the most medicinally powerful version of these plants.” So it was really through oral communication from other people in the community.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And Rosa’s grandmother started to take those lessons that she learned and apply them because the knowledge about medicinal plants and how to properly use them was essential to her community.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

There was very limited access to doctors, so people would go to the elderly in the communities like my grandma. And so she was used to having every tool in this case, literally plants, in the back of her house. And so when they moved to the city, she never wanted to lose that. So she built a small natural pharmacy in our backyard.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And Rosa spent her afterschool hours watching her grandmother tinker with this natural pharmacy.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

I remember actually one day I did cut my finger and we were in the jungle, so she just brought something that looked like thick blood. It was resin from a medicinal tree nearby. I got this thick red thing onto my finger and then I would spread it and it would become white like a cream.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Even though Rosa was surrounded by all of this amazing medicinal knowledge from her grandmother’s backyard pharmacy, the science that really captured her imagination when she was young was actually not the one in the small world right in front of her, but one in the vast universe, millions of miles away.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

I don’t know where it came from. I’m sure I must have seen a movie or an interview or something. But my grandma remembers that when I was three years old, according to her, I came one time from school directly to the garden and was like pulling on her skirt, telling her that one day I was going to be up there in the sky and I pointed and I said, “I’m going to be an astronaut.” I became obsessed. She says for an entire few days I would just run behind her saying like, “Space, space, astronaut, I’m going to be an astronaut.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Seeing her interest, her parents got her some kids’ books about space, but before long, Rosa started reading way more advanced stuff, books about physics and space exploration. And the more she read, the more her obsession grew.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

I had to literally look up what are the requirements to go to space? But I remember reading that you needed to pass very extreme physical tests and have perfect vision. So I said, “Okay, I’m going to commit my life to do all these things. I’m going to be in perfect shape and I’m going to learn how to swim.” When I was around 15, I convinced myself that I needed to be an expert in physics so then I could become an astronaut. I had chosen physics as one of my most advanced science classes.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But there was one reality that Rosa hadn’t accounted for.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

I felt like I was just beyond the concepts that I was used to seeing in my day-to-day life, like plants. I just could not grasp it for whatever reason. And then I said, “I really love physics, but what if I just try something that feels a bit more natural for a change?” I went to my professors and I said, “Well, hey, could I add a second science object? I want to explore biology a bit more.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

It was during this biology class that Rosa took a trip to the jungle, unlike any other she’s taken before.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

They said, “Okay, we’re going to go to a research lodge in the Amazon.” Which happens to be in Madre de Dios in the southern Peruvian Amazon. That is actually considered the most biodiverse area of the Amazon rainforest.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

They spent a week in the Amazon exploring the jungle, asking scientific questions about everything they were observing in the field.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

We had to physically enter different parts of the Amazon River and its tributaries to be able to measure water flow and volume and density. And so it was the first time I approached the jungle with a scientific mindset.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

One night as Rosa and her classmates were camping in the middle of the jungle, something clicked into place for her.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Everything in the jungle come to life in the evening, the sounds, the smells, the sensations, all of this feeling of being deep in the jungle, and just remembering that as a kid, I was already visiting the jungle so often because of my family, but I had never gone to the jungle with the idea to do science. And that to me, I think was the missing piece at the time.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And she started thinking about her family’s knowledge about the jungle, the intuitive way her grandmother used plants. And Rosa made a connection between what she’d been studying in her biology class with her grandmother’s natural pharmacy. She realized there must be scientific explanations behind all of these plant medicines.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Because we already had spent a few days asking scientific questions, ask questions about the water, about the plants, about the animals. And I remember one of my first thought was, what about the microbes here? And I remember looking up, it was a clear sky. It was just so beautiful. You could see almost the whole Milky Way. And just remembering that as a kid I wanted to go to space, but then all of a sudden exploring what I had around me became just as fascinating and just as urgent.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

She had all these questions about the microbial life of the jungle, and she couldn’t wait to look them up as soon as she returned from her school trip.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

But of course, as soon as I get to my computer and start to look it up on the internet, there was very little work done on Amazonian microbes as a whole and much less done in the Peruvian Amazon. And I just thought that that felt like a slap in the face. I said, “Well, I know that we’ve been to the moon and I know we have all these technologies for International Space Station, and how on earth can we not know what’s on the microbial space in the Amazon?” To me, it felt so obvious that if you know microbes are needed to maintain an ecosystem healthy, how can you not know what you have there?

And so as a young 15, 16 year old, it just felt like such a betrayal that I was like, “Well, no, this is not okay.” And then all of a sudden it’s as if my brain expanded what was possible for me.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Rosa realized if she wanted to know about the microorganisms that are living in the Amazon jungle, the place she’s been visiting and exploring her whole life, she would have to be the one to do it. But to bring that kind of science back to her home country, she would first have to leave her family and her home behind. More on that after the break.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

After realizing that there was virtually no scientific research on microbes in the Amazon, Rosa took her curiosity about outer space and inverted it, instead focusing her attention on the tiny cellular level.

And after graduating high school, Rosa left her family behind in Peru and moved to the United States to study molecular biology. As the first person in her family to leave home in pursuit of her studies, this was a big deal for her and her family, but especially for her grandmother.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

My grandma just had an eagerness to learn, and she always said she wanted to become a medical doctor. That was her dream.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But because Rosa’s grandmother made the sacrifice to put her siblings and children in school, she never got the opportunity to pursue a formal education for herself. She didn’t get to go to medical school or learn about the scientific explanations behind the plant medicines she was practicing so intuitively.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

But she had so much knowledge. And then she just told me, “Well, if you study, then you can come and tell me why it works.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And that’s what Rosa did. She went off and studied all about microbes and the invisible processes that take place inside these tiny organisms. And the more she learned about microbes, the more she understood all the ways they’re so impactful, not just in discovering new medicines, but to all aspects of life on our planet.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

To give you an idea, cyanobacteria, which is a type of microbe, they were the ones that make life habitable in our planet.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So Earth’s early atmosphere was made up of carbon dioxide and methane, gases that animals like us can’t breathe, but cyanobacteria have the amazing ability to photosynthesize. They use energy from sunlight to perform a series of chemical reactions to create fuel for themselves. But the best part for us is the byproduct of this process.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

They were the first microorganisms to start releasing oxygen that we could all breathe, thus making life on earth possible for all of us.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So microbes literally made our existence on the planet possible. And to this day, microbes are still impacting our ecosystem in really significant ways, from cleaning up our environment by reducing toxic gases like carbon dioxide and methane to keeping our soil fertile. But despite how much impact microbes have on the environment, they have been largely excluded from the bigger picture of our ecosystem. For instance, most of the computational models scientists use to predict how climate change is impacting the planet don’t include any microbial data, leaving us with a lot of unanswered questions. And this biased view that we have really distorts the way we think of how our ecosystem works because we’re looking at the world with this giant blind spot.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

For a long time, for example, microbes were not thought to be able to live in extreme hot conditions or in extreme acidic conditions because us as humans or small mammals couldn’t live in there.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

But Rosa knew that wasn’t the case.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Microbes break all of these boundaries. They do not follow the same rules.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And this is why when Rosa heard about the boiling river extreme environment deep in the Amazon jungle, she knew she wanted this to be the focus of her PhD research at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

And I remember hearing it before I could even see it because you can hear the constant blurbing of the water and the splashes. And then all of a sudden the very first thing that I saw was all this massive body of vapor. It almost felt like the clouds had kind of come down. Only a few that are slippery and get closer. I had visited so many areas of the Amazon, but that was the first feeling that I had of, it felt mystical.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

After doing a lot of research, Rosa not only confirmed that the boiling river was in fact a real place, she was also able to connect with a group of fellow researchers from different international institutions who were also interested in studying the river. In 2019, Rosa and her team embarked on the largest scientific exploration of the boiling river. They were there to study different aspects of the river from its flora and fauna to geothermal activities. And as the microbial scientist in the expedition, Rosa’s goal was to find out what kind of tiny organisms can live in this extreme ecosystem.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

People thought, well, it’s such a hot environment, reaching over 99 Celsius or 200 Fahrenheit, that anything alive that falls into it will die quite immediately, will boil from inside out. However, once we started exploration of this river, we could see quite quickly that was actually not the case. You do have things growing in the river, and it’s actually quite obvious if you know how to look for them.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

As a bear researcher, I know what to look for when tracking bears in the wild. I’d look for bear tracks or scat, but how do you look for microbes? I mean, they’re invisible.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Sometimes some microbes can create such large communities that they become visible to the naked eye.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

These large communities of microbes are called microbial mats, and that’s what Rosa was looking for in the boiling river.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

You look for certain type of greens, pinks, oranges, blues, and all of these reflect different type of microbes that have made their boiling river their home. And we call these microbes extremophiles because they like to live in the extremes and specific, these ones are called thermophiles because they love thermo, meaning they love the heat. And so they have adapted over thousands and thousands of years in order to thrive and live where nothing else can. And so part of our goals was to study the DNA encoded within these microorganisms so that we could learn how are they able to survive in these extreme conditions, what kind of molecules they could be making in order to aid in the survival.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

To answer these questions, first Rosa needed to get samples of these microbes so she could bring them back to her lab at the University of Michigan, which might sound straightforward. I mean, I have also done expeditions in some remote and extreme environments, but I’ve never had boiling water as my field site. So to me, this seems very intense.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

Part of our collection strategies in the field was always having a few team members around us so that one person could not be working alone because we realized you can get quite dizzy quite quickly actually, with the vapor and the heat and everything.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Following those protocols, Rosa explored the banks of the boiling river with her heat-resistant test tubes and gloves looking for signs of microbial life and collecting samples.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

And at some point we got to this area that my colleagues told me it was known as the Spider-Man wall, and I thought that was just a funny name. But I said, “Well, why?” And they explained that there was a specific part of the rocks next to the river that were quite hard to cross, but just from afar we could see that in this pristine area, there was a lot of microbial organisms that were just growing there in large communities, and they had these fascinating colors. We had seen already microbial mats along the river, but not this such shiny, green, bluish color. And so that to me indicated they’re, one, either producing different kind of molecules that is giving them this bluish color.

Or two, absorbing different type of things in their environments, or they are just different organisms that we have not yet seen in the bowling river. So that immediately just from a visual perspective told me, well, we have to collect those samples because clearly there could be something else we don’t know. And the fact that less people were transiting in the area means that they’re going to be cleaner samples to work with.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

So there were legitimate scientific reasons why Rosa and her team needed to find a way to get to the other side of that Spider-Man wall. But even more than that…

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

They told me that from the research teams that had been accessing the area, only a few boys had crossed the area. And I said, “Well, no girls have done it yet?” And they said, “Well, no, nobody really wanted to do it just yet, or there was no time or no rock climbing experience.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

As Rosa’s friend, I know that she’s a badass, but people have often underestimated her because of the way she looks.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

I would say one of the biggest prejudices that I have felt personally is the, “Oh, but you look a bit too girly girl to be going on explorations. I just don’t believe you’ll be going into the jungle. I just could not see it.”

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

I’m also a scientist who likes to go on big expeditions to wild places and also come back and get dressed up and look a little glamorous. So I can totally relate to what Rosa is saying, and it’s just such a narrow view of what a scientific explorer can look like. And even when no one’s actually saying these things to our faces out loud, people like us sometimes can’t help but want to prove like, “No, we can do this. Watch me.”

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

So I said, “Well, no, let’s just change that. Plus, I’m really interested in getting those samples and I feel more comfortable if I collect them myself.” Since I was the experienced microbial scientist.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And this is how Rosa ended up on the side of a slippery rock wall over a boiling river.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

The waters were in 80 Celsius temperature, so extremely hot. So not only do you need to be holding onto your life on this rock that is a little slippery and has these splashes of boiling water, but you also have all sorts of creatures like spiders and whatnot. And if you do one wrong step, you are into boiling water.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Luckily, there were two field guides on Rosa’s team who had crossed the Spider-Man wall before. So they went first while Rosa watched them closely so she could follow their steps.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

And I was freaking out and thinking my mother was going to kill me if she found out. And so I just started, put my hair up, just put my tools on the sides of my pockets and just started to do it very slowly, cautiously. And I thought about every step a million times before I took it, but once I took it, I just went for it as if there was no other option. Now, mind you that I had to cross with all the equipment literally on my hips. So I couldn’t take all that much with me, I had to take just the necessary.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And because the heat and the steam could make you dizzy, Rosa had to work really quickly collecting samples while also holding on to the rock wall.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

I had to really tip-toe and incline myself to get to the samples that were the closest to the hotter springs in the area and spoon a little bit of the sample. Sometimes it would just come off quite quickly like ice cream, but sometimes it was really holding onto the rock, and so you had to tap in a little harder and all of these process has to happen as sterile as possible, while also making sure you stay alive. And I became the first girl in these expeditions to cross the Spider-Man wall in the boiling river, and it was awesome. We got an amazing sample from it as well.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

Rosa’s being a little modest here because she’s truly a trailblazer, and I’m not just talking about crossing the Spider-Man wall to get those samples. But being a Peruvian woman scientist who’s doing this in-depth scientific exploration in the Amazon, because historically this kind of scientific expedition had mostly been done by western white scientists. And by doing this science in her home country, she’s actually going to be able to share her discoveries with the entire world.

Back in her lab at the University of Michigan, Rosa and her team are working away to analyze the samples she collected from the boiling river. They’re still finalizing the results of their research before sharing them with the public, but the initial findings look super promising.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

What I can tell you is that we have been able to grow some extreme forms of these microbes actually in the laboratory.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And considering how hard it is to grow microbes in the lab, this is a huge feat. Because being able to grow these microbes in a controlled environment means scientists will be able to do a deeper analysis and discover more things about them.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

And by looking at these microbes in this extreme location, in the heart of one of the most biodiverse areas of our planet, we are also able to find really interesting molecules that could have a direct real time impact in medicine.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

I can’t wait to see what they’ll find. The potential for new discoveries is huge, and these new findings are not only useful in the search for new medicines or environmental solutions, but Rosa and her team are little by little chipping away at the unknown 99% of the microbial world and giving us a better understanding of the invisible parts of our ecosystem. Because there are all sorts of invisible forces that sustain our world, whether it’s the microbes Rosa studies, or the badass women who paved the way for her to do this work.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

The invisible labor of the women in my family, to me, that is so much bigger than I could even imagine. It’s a reason as to why I’ve been able to have such beautiful upbringing and all these awesome opportunities to be able to grow and to explore, and to go around and have education.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

And understanding the invisible forces around us can help us have a less biased view of the world.

Dr. Rosa Vásquez Espinoza:

I want for people to think about Amazonian biodiversity beyond the exotic plants and jaguars and anacondas that we often have seen in movies or in books. I want people to think farther than that and look at the more micro, tinier life forms that are just as beautiful and important for the Amazon rainforest.

Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant:

As Rosa realized in that quiet moment in the jungle all those years ago, there’s an entire vast universe right here under our noses that’s worth exploring. Because let’s face it, from invisible microbes to apex predators, to the ocean that covers the surface of our planet, everything is connected and we will continue to explore just how deep this interconnection goes through the rest of this season of Going Wild.

Land Acknowledgement

As we’re delving in to all the different ways the natural world is interconnected in this season, we realized that the past, present and future are also connected. With that in mind, we’ve created a land acknowledgement for each episode where you can learn more about the land and the peoples that reside in the locations where each story takes place.

We would like to take a moment to acknowledge Puerto Inca Province, Peru, the location where Dr. Rosa Vazquez Espinoza collected her microbial samples.

The city of Puerto Inca which is the capital of Puerto Inca Province in Peru sits on the homelands of the Quechua, Ashaninka and Aymara Indigenous peoples. We acknowledge that this is their ancient homeland from time immemorial and continues to be so to this day. For thousands of years these Native peoples lived, cultivated their natural environment and built great civilizations.

We further acknowledge their tremendous past, vibrant present and future. As well as their continuing role as caretakers and stewards of these lands where they still live.

The Quechua people were the founders of the mighty Inca Empire, one of the great civilizations of the Western Hemisphere and pretty much the entire ancient world.

They built magnificent cities, with ingenious irrigation systems. Many accounts recorded that no one was ill housed or ill clothed, and there was no poverty in Inca lands. It was recorded that their system of government ensured that all the needs of the people were more than adequately provided.

Similarly, the Aymara were the founders of ancient Indigenous kingdoms, the ruins of which are still standing and can be seen to this day. They too had complex societies based on preservation of the environment, status organization and economic sharing.

The Ashinanka were and still are noted for their fierce independence. Their fighting spirit and skills ensured that their lands wouldn’t be easily invaded by intruders.

When they were invaded by Spaniards in the 16th Century, conquest and genocide followed resulting in the extermination of millions of the Indigenous inhabitants. But their courage, resistance and resiliency ensured their continued survival under the most adverse political, social and economic conditions.

Today the Indigenous peoples are continuing to advance and thrive, with populations in the millions and their traditions and ways of life still intact. The Native peoples are major contributors to the political, social, economic and cultural life of Peru and they foresee a future of ever growing strength in their traditional homelands.

Credits

You just listened to Going Wild with Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant. If you want to support us, you can follow Going Wild on your favorite podcast-listening app. And while you’re there, please leave us a review.

You can also get updates and bonus content by following me, Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant, and PBS Nature on Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, and Facebook. You can find more information on all of our guests this season in each episode’s show notes. And you can catch new episodes of Nature, Wednesdays at 8/7 Central on PBS, pbs.org/nature, and the PBS video app.