I had never, and I really mean never heard of a single scientist who had gone to do field work in any capacity who by themselves brought a toddler along with them.

I remember thinking this is either going to be the most triumphant, life changing adventure ever, or it’s going to be a complete disaster, and I could just lose it all.

Toddlers and big carnivores don’t exactly mix well.

THEME

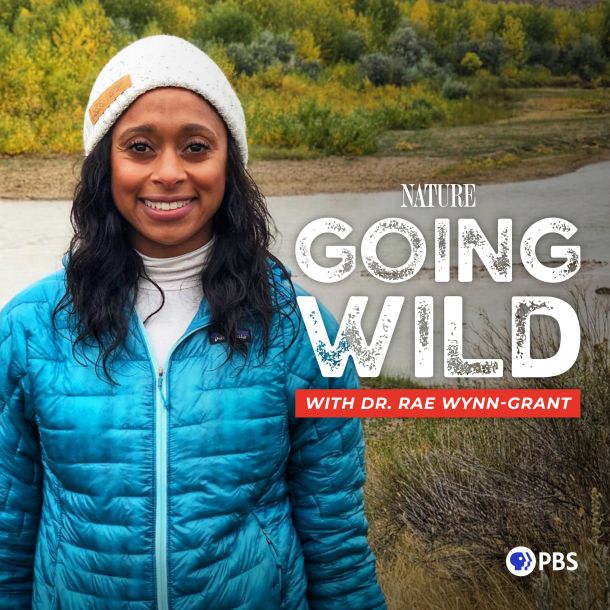

I’m Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant. And this is a different kind of nature show: a podcast all about the human drama of saving animals

This season, I want to share my story.

But I also want to introduce you to other amazing wildlife scientists: some of my friends who study hyenas, work with lizards, and even track sharks.

The animals we study are great, but who we are as people… and how that affects our work… is just as interesting. And we’re going to talk all about it.

This is Going Wild.

INTRO

So, this was the summer of 2017. I had a really cool job at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Although it was an amazing job at a really reputable institution, it was just a temporary job because it was funded by a grant and the grant was only for a few years.

Something that was always on my mind was like, where am I going to work? You know, like, where am I going to really land as a scientist?

And also at that point in my career, I really wanted more.

I had really been building up to what I thought was a dream career where I was traveling the world and going to all these amazing places, looking for wild animals and trying to do the work to save them. And I wanted to make sure I could continue being that bad-ass research scientist and not just, you know, someone who works at a museum with the stuffed animals… the taxidermied animals.

And so for a while it seemed totally possible for me to continue that research life that I had been doing for years, but then I became a wife and a mother.

I feel like there’s this thing that I used to hear: marriage doesn’t change your relationship that much; having kids is what really changes a relationship. And that might not be the case for everybody, but I can say that was definitely the case for me.

I gave birth to Zuri in the summer of 2015.

In all the years that I was a scientist before having Zuri, I would travel for research so much. So not just frequently, but also for extended periods of time. I mean, it wasn’t abnormal for me to go off and be in the field for three months.

I had the extremeness of the field life and I had the extremeness of this, like, cool urban young adult life in New York City. And that felt like such a great balance to me. And it felt like exactly who I was.

But in those first two years of Zuri’s life, I had only been on two expeditions and it’s notable because they were very, very short compared to what I used to do. And although they were great trips that took me into some wonderful, wonderful places, it was a different kind of stress that I experienced because I had the emotional guilt of being so far away for a long time.

And then there was, of course, the extra burden of childcare. In order for me to actually get away. I had to set up all kinds of things on the backend that I had never had to do before.

The realities of my life at that time was that I worked full-time and my husband, his work, started at 9:00 AM and most days he didn’t walk back into the door until 9:00 PM when the baby was already, you know, tucked in.

I didn’t make very much money in my position at the Natural History Museum. Anyone out there with a similar position knows it’s like barely a livable wage, especially in New York City.

With a two-year-old little girl, we prioritized his being at work over my being at work because his job actually paid the bills and kept a roof over our head.

Essentially, he thought that I should leave that field life behind and figure out a way to do science from the comfort of an office so that I could consistently be home.

There were several times where he would really express, like, “You’re a mom now, so you have to reel it in.”

That kind of thing made me angry because I didn’t want that. I still had this passion and this fire, it wasn’t like diminished because I had had a baby.

And it’s embarrassing to admit, but I can honestly say that I used to sometimes daydream about not being married and not being a mother. I thought of myself as really selfish for continuing to want to have this adventurous wildlife career while also knowing that I was responsible for a little person.

All of a sudden, all of these things inside of me were put to the test: what I really truly wanted, you know, what my family needed, what my husband kind of secretly wanted… All of these interests and decisions just came front and center all at once.

I was having a conversation with a colleague of mine who was also a good friend and who also did a lot of work in the tropics. He said that he knew people who were studying Jaguars down in central America, down in Panama. And he was suggesting that maybe that could be a really good place for me to get some experience with different carnivores.

And what he was talking about wasn’t just, just any old carnivore, right? Like it was Jaguars. To me, Jaguars are completely iconic, right? Like, one of the most fascinating big cats, especially, you know, in the Americas.

Maybe even more importantly, Jaguars are an endangered species. So the idea of studying Jaguars, you know, actively working on the science that can help, bring their populations back you know, all of this was so, so incredibly appealing.

And then the very best part of all of it was that all the details were already worked out. My friend had said that he had it all handled. He was going to take that burden off of me and arrange everything which was a huge relief for me.

So, all of this made it way easier to say a resounding yes to the expedition because while all of those details are being taken care of, I was able to really focus on what I was going to do with Zuri back at home for those two weeks I’d be gone.

The past couple of times that I’d been away for expeditions, I had relied so heavily on my mom’s help. Like, she would literally come up from where she lived and move into our house for a little bit of time to help take care of her. So, I called my mom and I told her about this awesome opportunity in Panama and she was so excited about it and really happy for me. And then I gave her the dates.

I don’t remember what it was now, but at the time there was some big obligation that she absolutely could not work around and she couldn’t do it.

I think I played it off you know, I said like, “Oh, don’t worry about it. I’ll ask my husband and I’m sure we’ll figure something out.

And when I told him he rolled his eyes and it really hurt my feelings.

He wasn’t excited. He wasn’t excited about this trip. He wasn’t excited about Jaguars. He just said no. And he said no to the whole expedition.

And I was kind of expecting him to say no or to not be supportive, but it still hurt so bad. And it made me wonder if he essentially wanted me to be a different person. If he really desired a different version of Rae, one that was essentially settling for something easier and more convenient versus daring and adventurous and exciting.

Man, going to have to let this dream research opportunity pass me by because it’s also important for me to be responsible for my daughter.

But for whatever reason at that point in my life I was not willing to take “no” for an answer.

I remember telling myself, like, “I’m not gonna let parenting be a barrier to my career success or my joy.” Because if I didn’t go on this trip to Panama, if I allowed myself to miss this opportunity, that maybe that would be a domino that rippled through the rest of my life. And maybe I would always be saying, no, you know, that like becoming a parent obscured me from the path that I wanted to be on.

This like kind of crazy thought came to my mind, which was, well, what if I brought Zuri to the field with me?

I had never, and I really mean never heard of a single scientist who had gone to do field work in any capacity who by themselves brought a toddler along with them. And so I don’t know what led me to think this was a good idea.

“This could be it. you know, doing something so new that you’ve never even seen modeled by someone else.” This could be the ticket to freedom, you know, like emotional freedom, career freedom, it could the thing that changes my husband’s mind and, and prove to my husband that I was capable, you know, that I was able to succeed in being, you know, a wife, a mother, a bad-ass field researcher, and that he would kind of be forced to accept that because I would like throw it in his face.

When I went to my husband, he was like, “Even though I don’t like it, you can do it.” That was kind of the response from him.

There’s this picture that I took at the airport. My daughter is in her stroller and I’m holding onto her favorite stuffy, which was a giant orange popsicle that we called “Creamsicle.”

I have this big backpack on my back and a diaper bag on my shoulder. And I took this picture and I posted it on social media. And I had some like caption that said something like, “When you don’t have a babysitter, but you have to go to the field to study Jaguars.”

And I posted it feeling like edgy and cool, you know, like a real explorer.

When I look back at these pictures now I just think to myself, oh my gosh, she has no idea what’s about to happen.

We stepped off the plane in Panama and everything was great. The air was all humid like it is in the tropics and when we got outside of the airport my friend was there. Just like he said he’d be.

We all piled in the car and we drove several hours from Panama city all the way down to the village that was right at the edge of the rainforest.

THE PROJECT

So if I thought finding bears were hard, finding Jaguars is way more difficult.

First of all, the jungle itself is super, super dense, so it’s just hard to find things on the landscape anyway. And then second, jaguars themselves are super elusive. I mean, that’s what makes them incredible predators: they can sneak up on their prey without ever being seen. And Jaguars are territorial. There’s only one Jaguar per region. And so all of these things about Jaguars make them so difficult to find and study.

So our plan was to go and look for evidence of Jaguar presence, like poop or a kill that they recently had, and then set some camera traps, capture images of them, and then trap them and put GPS collars on as many Jaguars as possible so we could understand their movements and their habitat preferences. And so knowing which areas they use can help us make recommendations for which areas to conserve.

The next day, I woke up super early and grabbed Zuri, took her into the village so that we could chat with some people because what I needed was to find someone who’d be able to take care of her.

I wasn’t actually going to be taking her into the jungle actually looking for jaguars. Toddlers and big carnivores don’t exactly mix well. So I was looking for a nanny who could take care of her back in the village while I was out properly doing the field.

It didn’t take long at all to interview someone who I felt was perfect for the job. I hired her on the spot. And with that all squared away I was so ready to be able to switch my focus to the project at hand: finding these jaguars in the rainforest.

And I know that the first step is to meet up with the researchers who have already mapped out the jaguar study.

And so I turned to my friend and I asked him, “Okay, what’s the plan? When are we getting out there?”

And so then… crickets.

Because, turns out, he hadn’t actually heard back from any of the researchers yet. And he had all these excuses like, “Oh, they spend so much time out in the field” or “It’s difficult to reach them when they’re not plugged in.” Or “They’re just always really bad at getting back to me about this stuff.”

Honestly, this should have been a huge red flag. I mean, it’s totally not normal to begin an expedition without any communication with the people that we’re gonna work with. But instead of me taking the red flag, I really trusted my colleague and my friend. And so I just went with.

And over the next couple of days, it was delay after delay, after delay.

Ugh.

And all of these delays made me feel so many different ways. It made me feel angry. It made me feel terrified. It made me feel suspicious. and it ultimately made me question, like, had I done all of this, had I moved all of these mountains and brought me and my daughter to Panama essentially for nothing to pan out?

But at the same time, you know, we were there, we were in Panama and I’m, you know, a pretty optimistic person. So I decided to make the best of it.

And it wasn’t all bad, right? Like we still living in this house in this village on the outskirts of a rainforest. So the simple act of taking a walk with my daughter like down the street was magnificent.

There were interesting frogs. I remember she fell in love with leaf cutter ants.

Literally it was like watching a nature show, you know, like these ants, these big ants, carrying these like even bigger pieces of leaves, you know, like up and down a giant tropical tree.

And I remember having this moment where I realized that out of every single person in my family, including my husband, no one had ever come with me to the field. So it meant so much to know that I had my little buddy, my daughter with me actually seeing the proof of concept of what it means when mommy has to go around the world and travel for wildlife.

She was there. She was with me, she was present and she was learning and experiencing right along with me. And that was super special.

But a couple of days in, I realized like, gosh, this feels way more like a vacation than the hardcore expedition that we’re trying to do. And it ends up being day five or day six and we still haven’t heard back from any of these researchers that we’re waiting on and we haven’t even gone into the field at all.

And so in the middle of one of these days, I put Zuri down for her afternoon nap. I found my friend in the house and I had a serious confrontation.

“I did not fly all the way from New York to Panama with my toddler, putting my whole marriage in jeopardy, to come back empty handed from this whole thing.” We had to make something happen and we needed to get our butts into that rainforest.

And so his reaction was essentially like, “okay, you’re right. Let’s at least just go and try to find these researchers.”

MIDROLL

If someone had asked me, like, what does the rain forest sound like? I would have said like, “It’s noisy, but in a consistent way. Right? Like always the squawks of birds and the like hum of insects and the sound of rain drops falling.”

I probably wouldn’t have said, “This like mellow noise and then like chaos, chaos, chaos!”

The Howler monkeys, weren’t just howling for no reason, they were howling because I was under their tree and they didn’t like it very much. Like, they would throw things down like fruit and stuff from the top of the tree, would scream at the top of their lungs. And then the whole group of them would grunt like in this loud, noisy frenzy.

We were hiking for hours on foot through the muddy rainforest. And not only did we not see a single researcher, we didn’t see a single other person. We didn’t even see evidence of these people. No camera traps, no gear, no flagging on the trees. Absolutely no signs of human life anywhere.

Listen, we’re never going to find these guys. We have to get back home before bedtime. This whole mission is essentially a huge failure.

We made our way down, you know, along a path for a while. And then, know, the path ended. And we got down to a little stream where I could wade through and cross the whole thing without the water coming up past my knees.

I took off my shoes and I pulled up my pants right above my knees.

And on the banks of this stream is a lot of mud, and right before I put my foot down in this mud, I saw what was unequivocally a jaguar print.

It had that classic look of a big cat, like, you know, almost like the print of a house cat, but much, much larger. You could see the claw markings. It was absolutely beautiful. I froze in place because I realized, “Oh my gosh. Not only is this evidence that a jaguar had been right here, but there was reason to believe that the jaguar had been there really recently.”

Again, this is a rainforest. It rains all the time. It had rained like 30 minutes before that. So any prints we were seeing were guaranteed extremely fresh prints.

“Oh my God.” I shouted it really loud and I immediately instinctually pulled out my GPS unit and took a point so that we had the longitude and latitude of exactly where we had this jaguar print.

But at that time there was really nothing we could do with that information. It was a fun data point for me to have and take home with me, but we never got in touch with these researchers. So we couldn’t even share it with them.

And it was so frustrating.

To know that the jaguar was, was there. I mean, there was the print. And I was in the closest proximity I had ever been in my life maybe would ever be to a real wild jaguar that could have been watching me this whole entire time.

And although I never got to actually see one, in this kind of spiritual sense, it was almost like it was telling me that it was there and that it was okay. And that this was its habitat and yes, it needed to be protected.

So in the evening that I came back from the field, I changed my ticket so that Zuri and I could leave the very next day.

I told my friend, “Hey, you know what, do whatever you want. Stay here. Don’t stay here. I don’t care. But me and Zuri are out of here. I appreciate what you tried to do, but this isn’t working out. This isn’t what we agreed on.” And I need to step up and be a responsible adult get us out of here and back home safely.

At one point we’re flying and it was late in the day. Zuri had just finally fallen asleep for a nap and she had her stuffy Creamsicle with her and so she was kind of using Creamsicle as a pillow.

And I remember kind of looking over and realizing that, like, you know what, like she and I, we go places, we do stuff like we’re kind of peas in a pod. And if everything else falls away from this trip, I know she and I can be okay together.

What’s so interesting about reflecting on that moment is that, you know, it was shortly after that, that it became just me and her.

So, Panama essentially was a failure, right? Like the mission that I set out on did not happen in any way, shape, or form. And yet at the same time, it wasn’t a failure because that trip really set in motion, a huge life change for the better for me and for my family.

I was able to get crystal clear on the fact that I wanted an adventurous wildlife research life. And that required a different level of support from my husband or from a partner. And it required a different level of bravery and courage and self dependency from me. And although it was scary, it also seemed like undeniable, you know, I couldn’t run from it anymore. I had to just dive head in, even if that meant setting myself up for more uncertainty.

So, what did I do? Oh my gosh. I did some really important and really scary things. I mean, I left my research job as it was in order to find something that would give me a little bit more freedom and a lot more institutional support to be the researcher I wanted to be.

My husband and I started a pathway towards divorce. We broke up.

And I guess maybe the Panama experience helped me see that can’t always predict how things will end up. But if there’s one thing I can predict is that I can take care of myself and my daughter and I can depend on me.

Like I can bet on myself.

Just a couple of weeks ago at school, Zuri gave a presentation about leaf cutter ants. She wrote a report on them.

And I didn’t know she was doing this in advance, but I showed up and she gave her presentation on leaf cutter ants.

Afterwards I pulled her aside and I said, “Wow, do you remember when we went to Panama together and you were fascinated by the leaf cutter ants and how we watched them walk up and down the tree with these huge leaves in their mouths?”

And she doesn’t remember it. She was too little. And yet somehow I maintain that it impacted her in ways that she’ll never really know.

I mean, to begin with, she’s grown up knowing that she belongs in all kinds of spaces, including the outdoors. And that’s a really big difference from how I grew up.

And I really hope and believe that part of her joining me in the field and Panama can translate into her growing into a woman who feels strong in making her own choices. She won’t have these fears that, you know, she can’t do something out of the box or non-traditional or brand new. That it is possible and it might be scary and there might be feelings of being alone, but that she’s capable and that she can also bet on herself.

CREDITS

You just listened to Going Wild with Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant.

If you want to support us, you can follow “Going Wild” on your favorite podcast listening app. While you’re there, please leave us a review – it really helps.

You can also get updates and bonus content by following me, Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant, and PBS Nature on Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, and Facebook.

And you can catch new episodes of Nature Wednesdays at 8/7c on PBS, pbs.org/nature and the PBS Video app.

This episode of “Going Wild” was hosted by me, Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant. Production by Caroline Hadilaksono, Danielle Broza, Nathan Tobey, and Great Feeling Studios. Editing by Rachel Aronoff and Jakob Lewis. Sound design by Cariad Harmon.

Danielle Broza is the Digital Lead and Fred Kaufman is the Executive Producer for Nature.

Art for this podcast was created by Arianna Bollers and Karen Brazell.

Special thanks to Amanda Schmidt, Blanche Robertson, Jayne Lisi, Chelsey Saatkamp, and Karen Ho.

NATURE is an award-winning series created by The WNET Group and made possible by all of you. Funding for this podcast was provided by grants from the Anderson Family Fund, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and PBS.