It’s been called The Big Empty – an immense sea of sagebrush that once stretched 500,000 square miles across North America, exasperating thousands of westward-bound travelers as an endless place through which they had to pass to reach their destinations. Yet it’s far from empty, as those who look closely will discover. In this ecosystem anchored by the sage, eagles and antelope, badgers and lizards, rabbits, wrens, owls, prairie dogs, songbirds, hawks and migrating birds of all description make their homes. For one bird, however, it is a year-round home, as it has been for thousands of years. The Greater Sage-Grouse relies on the sage for everything and is found no place else. But their numbers are in decline. Two hundred years ago, there were as many as 16 million sage grouse; today, there may be fewer than 200,000.

The Sagebrush Sea tracks the Greater Sage-Grouse and other wildlife through the seasons as they struggle to survive in this rugged and changing landscape.

In early spring, male sage grouse move to open spaces, gathering in clearings known as leks to establish mating rights. They strut about, puffing up yellow air sacs in their breasts and making a series of popping sounds to intimidate other males. For weeks, they practice their elaborate display and square off with other arriving males, battling to establish dominance and territory. Successful males then display for discriminating females and are allowed to mate only if chosen as the most suitable. The criteria are a mystery to all but the females, nearly all of which select only one or two males on the lek each year. Once they’ve bred, the hens will head off into the protective sage to build their nests near food and water and raise their offspring alone. Within a month, the chicks hatch and follow the hens as they forage for food and keep a watchful eye out for predators. In the summer, the grouse head to wetlands, often populated by farms and ranches, in search of water, only to return to the sage in the fall. Shrinking wetlands that once supported thousands of grouse still manage to provide for hundreds.

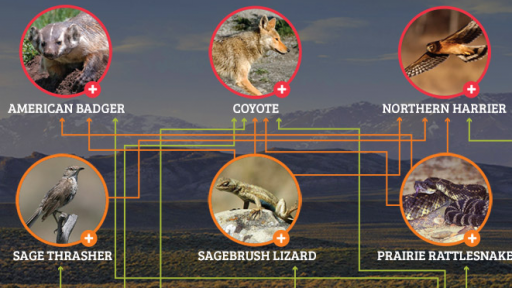

Other species discussed in the program include the golden eagle and great-horned owl. Both bird species take advantage of perfect perches on the rocks and ridges sculpted by the area’s constant wind to nest, hunt, and raise their families. Cavity-nesting bluebirds and the American kestrel return each year to raise their young in rock crevices. The sagebrush serves as a nursery for the sagebrush sparrow, the sage thrasher and the Brewer’s sparrow, all of which breed nowhere else.

Sage survives in this arid environment through deep roots that reach to the water below. Like water, however, many key resources are locked below ground in the high desert, bringing an increasing presence of wells, pipelines and housing. As they proliferate, the sage sea is becoming more and more fragmented, impacting habitats and migratory corridors. And of the 500,000 square miles of sagebrush steppe that stretched across North America, only half now remains. For the sage and the grouse, the future is uncertain.

In 2015, a cooperative agreement among western state, federal, and local partners protected 10 million acres of habitat to ensure survival of the Greater Sage-Grouse.

In December 2018, the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management revealed a plan to remove more than 8 million of these acres from protection, leaving the future of the species in the hands of state governments.