When Howard Hall graduated from college in California, he had a degree in zoology and a love of scuba diving. These days, he’s managed to combine the two interests into a successful career. NATURE spoke with Hall, one of the filmmakers behind Shark Mountain, a documentary about the abundant sea life around Cocos Island, in the Pacific Ocean off Costa Rica in November 2004.

How did you get into this line of work?

I started as a sport diving instructor when I was in college, where I got a degree in zoology. Then, I began looking for ways to make a living with my skills, and underwater photography seemed like a good one. It slowly evolved into a career.

Underwater filmmaking has seen some big advances in technology.

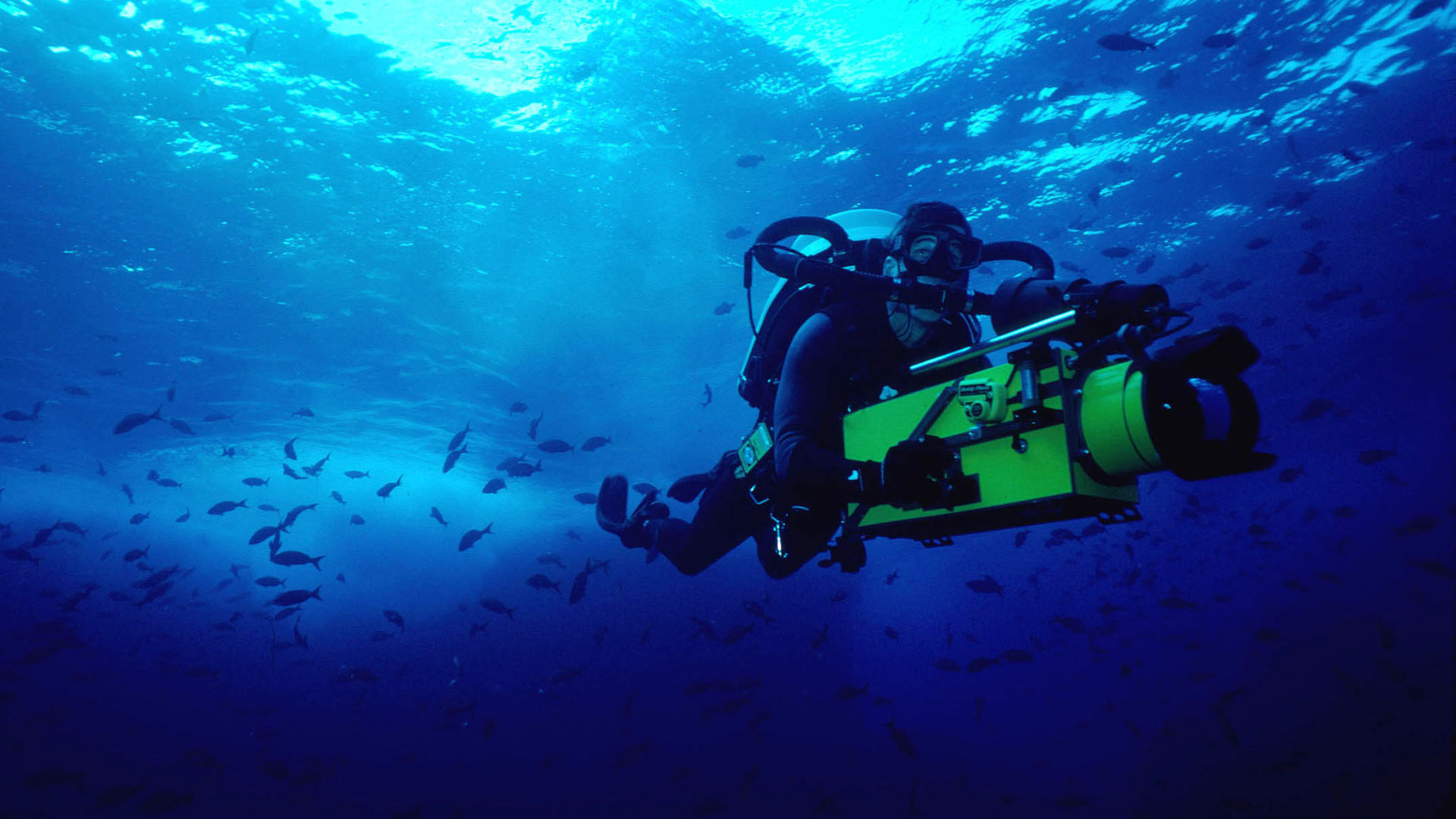

Yes, the technology both for diving and cameras has changed dramatically. In diving, we’re now using closed circuit mixed gas re-breathers that allow us to stay down longer and deeper. And we’ve switched to high definition cameras with lenses that do nearly everything, so we don’t have to change lenses anymore. Having said all that, however, I’m finding that it is harder to get the sequences I want for my films, simply because there are so many fewer animals now. So the technology is better, but the populations and ecosystems are declining.

Do you think your films can help reverse that decline?

There’s been a long controversy over whether conservation films do any good. But I know for a fact that the films we’ve shot at Cocos Island helped convince the Costa Rican government to ban the finning of sharks and take other conservation measures. Unfortunately, those laws aren’t always enforced. But the awareness is growing.

How did you find out about Cocos Island?

A friend of mine put in the first live aboard dive boat there, and invited me down on one of their first trips, back in about 1990. It was remarkable. [Since then,] we’ve made 3 films there, including an IMAX film that included 135 days of diving. So I’ve seen it change over a 15-year period, but it can be hard to track the changes. Some are due to natural fluctuations that happen over long time periods. Still, my impression is that there is less of everything now. In places where you once saw lots of hammerhead [sharks], you may not see a single hammerhead.

That makes some sense, because sharks are being fished all along South and Central America. But there are also fewer small animals, like jawfish and blennies, and it’s hard to explain why. Cocos is not unusual in that regard — every place I go I see less animals. There are some exceptions, but the general trend is to see less animals.

What are some of your favorite shots?

I’ve never gotten tired of filming the clouds of schooling hammerheads. That is one of the most amazing things you will ever see. Every time I shoot it I try to do it a little better. But it is hard to get a great shot, because [the waters around] Cocos can be dark and murky and every year there seem to be less sharks.

Any other sequence you are still looking to get?

A long while ago, I was diving and there were white tip reef sharks being cleaned by gobies. I went down, lay down beside them, and shot the little gobies swimming all over the place — in the sharks’ mouth, their gills. It was remarkable. Since that day, I’ve gone back to that same rock over and over again and never been able to shoot that sequence again. It’s been hugely frustrating! A lot of people assume that shooting the big animals — sharks, whales, dolphins — is the best thing about underwater work. But I almost prefer shooting the small animals. When you set up a camera and watch a small animal for a long time, you often catch behavior people know nothing about. There are many cases where we’ve learned entirely new things about fish. And some things that the experts said couldn’t happen, but did!

What’s next?

We’ll soon be shooting off the California coast for an IMAX 3D film about biodiversity in our world’s oceans. It’s mostly an animal behavior film, looking at the weird and interesting behaviors of some of these animals. It requires an IMAX camera in a housing that weighs 1500 pounds. But it’s a great project.

Good luck!

Thanks. It’s going to be a huge task that’s going to take a year or more.