They call it the Last Great Race. It covers nearly 1,200 miles across some of the toughest terrain on earth, through some of the bitterest winter weather in the world.

Still, there is something about Alaska’s Iditarod sled dog race that keeps competitors coming back year after year, eager to test their 16-dog teams and mushing skills against the elements and each other.

NATURE’s SLED DOGS: AN ALASKAN EPIC provides a compelling portrait of this competition, a test of endurance for both dog and driver. It follows several teams as they race to overcome the many obstacles, physical and psychological, they encounter along the trail. And it allows armchair mushers, if only for a moment, to share in both the spectacle and splendor of the Alaskan wilderness and the special bond that unites the racers with their partners, the sled dogs. “It’s an unbelievable adventure,” says Joe Runyan, the 1989 Iditarod champion.

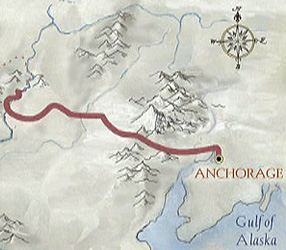

The Iditarod, held each March, isn’t a race for just anyone — or any dog. The route bumps along from Anchorage to Nome across rugged landscape, from mountains to sea ice, retracing an historic 1925 dash to bring desperately needed medicine to the children of Nome, who were threatened by a diphtheria epidemic. In 1967, Alaskan sled dog enthusiasts decided to memorialize the event and remind people of the sled dog’s proud place in Alaskan history; by 1973, it had evolved into the modern Iditarod. While experts don’t agree on what “Iditarod” means, many believe it is a Native American word meaning “distant place,” while “musher” is believed to come from the French word “marcher,” to walk.

Iditarod racers “face a tough new test at every turn in the trail,” says Runyan, a dog breeder and Iditarod consultant who lives in southern New Mexico. At the beginning, for instance, the 60 to 80 racers who start must battle the soft snows of Alaska’s coastal plain, then fight their way along the frozen Yukon River, “which is just a big wind tunnel in the winter,” says Runyan. Later, the teams must traverse the dark, frozen wastes of the Bering Sea into Nome. At each of the 26 checkpoints along the way, veterinarians carefully monitor the health of every dog, making sure they are up to the challenge. If for any reason a dog does not receive a stamp of approval from the vet, they are immediately airlifted out of the back country. Not even the mushers get this kind of support.

All told, the trip can take 10 days or more. While it took speed record holder Doug Swingley of Sims, MT, just nine days to complete the course in 1995, another racer named John Schultz needed 32 days, 15 hours, and 9 minutes to finish in 1973. But for most mushers, “if they finish at all, they feel like they’ve won,” says Runyan. He notes that racers typically get just a few hours of sleep a day while on the trail, traveling at night and sacrificing shut-eye to make sure their dogs are getting enough food and rest.

The differences between the top teams and the also-rans are often “imperceptible at the beginning of the race,” says Runyan. After 500 miles, however, “things begin to resolve themselves,” he says, with better-prepared teams pulling ahead into a tight leading pack, waiting for a chance to break away into the lead. Often, those in front have spent all year preparing their dogs for the race, spending $50,000 or more to maintain a kennel of well-fed, carefully-trained champions.

But strong dogs are only part of a winning formula. The driver’s attitude is also critical. “The musher has to keep a positive attitude, even if they have to fake it,” Runyan says. “The dogs really pick up on the emotions of the musher; a good attitude can make a good team even better.”

Desire also plays a big role. “If you are going to run the Iditarod, you’ve got to go to bed dreaming about it, mentally preparing yourself,” says Runyan. “You won’t find anyone in the lead pack without that desire.”

Indeed, in 1978 such desire denied another victory to Rick Swenson, an Alaskan who has won the race a record five times. After a tight battle across the state, Swenson entered the home stretch in Nome with a seemingly safe lead over his closest rival, fellow Alaskan Dick Mackey. But in a last-minute sprint that has become legendary, Mackey overtook Swenson in a photo finish, prevailing by just a single second. Such drama, Runyan says, “is what makes the Iditarod unique.”