About 750 miles up the coastline from the Peruvian capital city of Lima, a quiet fishing village called Cabo Blanco rests among the pale cliffs. Here, even in winter, a warm breeze blows over the white sand beaches. Atop a rocky hill, the dilapidated shell of a building overlooks the vast Pacific. The eaves are rotting, and the swimming pool has long been dry.

About 750 miles up the coastline from the Peruvian capital city of Lima, a quiet fishing village called Cabo Blanco rests among the pale cliffs. Here, even in winter, a warm breeze blows over the white sand beaches. Atop a rocky hill, the dilapidated shell of a building overlooks the vast Pacific. The eaves are rotting, and the swimming pool has long been dry.

These ruins are all that is left of the legendary Cabo Blanco Fishing Club, an exclusive resort for wealthy deep-sea fishermen who flocked there over half a century ago. Like Rick Rosenthal in Superfish, these men were on the hunt for “granders” — black marlin weighing in at over 1,000 pounds. Just a few miles offshore, the waters were so plentiful that sports fishermen didn’t bother trolling for their catch — they would simply throw their lines in the direction of the giant billfish they spotted from their boats. They called this place “Marlin Boulevard.” Back at the club, they celebrated their record hauls by lining the pathway with marlin tails and tossing back a drink at the bar.

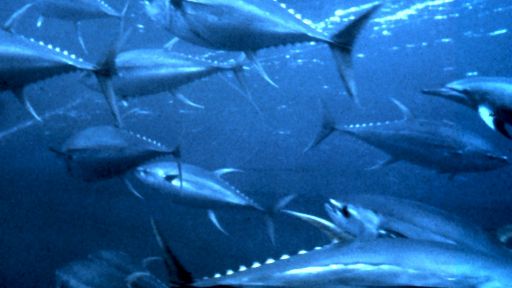

Standing on this hillside, looking out at the water, one can still see the ocean currents that brought this bountiful sea life to Cabo Blanco. Up and down the coastline, dark blue waves meet a bulwark of lighter blue water. Here, the icy waters of the Humboldt Current collide with warmer water from the Pacific Equatorial Current. Where they meet, upwellings of cold, nutrient-rich waters bring millions of plankton to the surface. Anchovies feed on the plankton. In turn, the anchovies support a breathtaking array of undersea creatures, including squid, sailfish, marlin, swordfish, and shark. But at no point in time were the waters here as rich with life as they were during the heyday of “Marlin Boulevard” in the 1950s and 60s.

On a sunny day in August 1953, one of the Fishing Club’s founders, Texas oil magnate Alfred C. Glassell, Jr., was fishing eight miles offshore. Suddenly, there was a violent tug on his line — something had grabbed onto his five-pound mackerel bait. For nearly an hour and forty-five minutes, Glassell wrangled his catch. When it finally surfaced he saw just how enormous the creature was. Again and again the massive black marlin leapt from the water, trying to free itself from the hook. But it was no match for Glassell. At 1,560 pounds and over 14-and-a-half feet long, it was — and still is — the largest bony fish ever caught by rod and reel.

In the years that followed, game fishermen who heard of Glassell’s giant catch swarmed to Cabo Blanco to try their luck. Among the celebrities said to have visited are Jimmy Stewart, John Wayne, and baseball player Ted Williams. Ernest Hemingway spent several weeks there during filming for the movie adaptation of his book The Old Man and the Sea. He later wrote, “We fished 32 days, from early morning until it was too rough to photograph and the seas ran like onrushing hills with snow blowing off the tops.” According to the locals, Hemingway himself hauled in ten marlins. Five decades later, however, it’s sometimes impossible to tell fact from legend.

The Cabo Blanco Fishing Club has been closed for decades. Like these distant memories, the granders have also faded away from Cabo Blanco. In the years that followed Glassell’s record-breaking catch, a dramatic increase in the commercial fishing of anchovies, which are often used for fishmeal or bait, led to a significant decline in this important billfish food source. According to some, a particularly severe El Niño event in the Pacific likely compounded their scarcity. In 1970, the Cabo Blanco Fishing Club finally closed its doors, due to the military rule of General Juan Velasco Alvarado and the hostile environment toward North Americans his policies engendered. The giant billfish were gone, and so were the tourists.

Today, Peru’s commercial fisheries continue to harvest the sea. It is an endless process, driven in part by the poverty of seaside villages. Nearly one-fifth of the world’s total fishing catch comes from the Humboldt Current ecosystem, yet local fishermen make only pennies on the pound. Rick Rosenthal thinks our insatiable appetite for seafood is having dangerous consequences. In Superfish, Rick watches the fishermen unload their bounty on the docks. “It’s taken away by truck and put on a plane, and most of it going to the United States,” he explains.

In recent years, however, the Peruvian government has taken steps to prevent overfishing. In 1999, Peru’s maritime research institute, Imarpe, joined with the fisheries ministry to institute a satellite tracking system to help monitor the country’s entire fleet of fishing vessels. Boat owners foot the cost of renting the mandated equipment, which relays data about water temperature and salinity (to help identify the occurrence of upwellings) as well as information about the types and quantities of fish that are caught. All of the data is tracked by a central system, allowing the government to better manage temporary fishing bans and other sustainability measures. On April 2, 2008, Peruvian president Allan Garcia signed a Presidential Order that, effective immediately, will ban the commercial harvest of billfish in the country’s waters. Developed in cooperation with The Billfish Foundation, a Florida-based non-profit dedicated to conserving billfish populations, the plan also includes other conservation measures and promotes a sustainable, catch-and-release sportsfishing industry in Peru.

Many conservationists see sportsfishing as animal exploitation and thus oppose the practice outright. However, tourism generated by the sportsfishing industry in Peru could provide an economic boon that may help some in poverty-stricken coastal communities shake their dependence on commercial fishing, which many fear is irreversibly depleting the ocean’s ecosystems.

Time will tell if the government’s measures will help spur an ecological revival here. For now, however, the village of Cabo Blanco can only reminisce about its glory days long past.