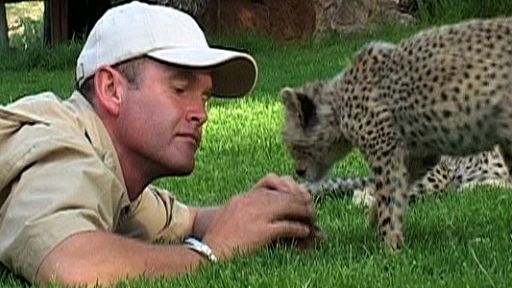

NATURE goes behind the scenes of The Cheetah Orphans in an interview with filmmaker Simon King.

Why was it so important for you to take a role in these cheetahs’ lives? How rare are cheetahs? How important is it for them to reproduce?

There are fewer than 13,000 cheetahs left in the wild, probably far fewer, though figures for some African countries are hard to tally. Every single one of them counts. Without human help, these cubs would certainly have died, their mother having been killed by a lion in a remote part of Northern Kenya. The cubs were discovered by some Samburu boys, and brought to Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. [The cheetahs] were exhausted, dehydrated and emaciated — on the verge of death. They were brought back from the brink by Jane and Ian Craig, who have tremendous experience with raising orphaned creatures. I first heard about [the cheetahs] when they had been with the Craigs for about four weeks and immediately offered my help.

What other options were there for the cheetah orphans besides you taking on their education? Was there any chance a wild cheetah mother could have adopted them?

There was very little chance of a wild cheetah mother adopting the cubs. First of all, one would have to find a wild mother with cubs of precisely the same age. And then, there is little chance such a mother would accept the offspring of another female. She would be very likely to reject and even injure them. The cubs were at death’s door. They could either be saved by human hand, or left to perish.

In the wild, would both parents be involved in raising the litter?

Only the female cheetah raises the young. The father has nothing whatsoever to do with the family. He may, from time to time, come and inspect the female, but this is more to see if she is ready to mate once more than through any fatherly tendencies!

Describe your commitment level once you made the decision to raise the cheetahs. How much time did you spend each day teaching Toki and Sambu?

Had the cubs died in the field, since they had been left alone after their mother had been killed by a lion, one could argue it would have been a natural end to their short lives. The moment human beings became involved in their welfare, I believe we all had a responsibility to try and do the very best for them for as long as was necessary. I shared the job of caring for the cubs with my wife, Marguerite, the Craig family and a few members of the Lewa Wildlife team, most notably Stephen Yiasoi Siapan, a local Masai whose affinity for Toki and Sambu was very special. Between all of us, the cubs had 24-hour care for the first months of their life. As the cheetahs matured, we maintained the 24-hour vigil at first and then kept watch for 14 hours a day (all daylight hours).

Do baby cheetahs normally bond as strongly as Sambu and Toki did?

Cheetah cubs always form a very strong bond. This is particularly important for male cheetahs (Toki and Sambu were both male) since the bond will last through to adulthood. A coalition of male cheetahs has a far greater chance of breeding with females they encounter than do solitary males.

When you and Stephen babysat Toki day and night after Sambu died, he was not only tolerant of your presence but he almost seemed to expect that one of you would sleep beside him at night. Did Toki or Sambu’s acceptance of you and Stephen surprise you? Is it common for human-raised cheetahs to get so attached to their caretakers?

However, the downside of this was that spending time with him undid a lot of work we had put in to try and distance ourselves from the brothers. Just before Sambu died, both Toki and Sambu were living wild lives, hunting entirely for themselves and were very wary of humans they did not know. After Sambu’s death, I felt Toki needed the protection and support of his human guardians once more. Our close contact helped him to survive, but meant that we had to start again with getting him to be fully independent and distrustful of people.

I was not surprised by his acceptance of us; he had known us all his life. It was very touching though. Toki was very distressed after his brother Sambu was killed by a lion. He had come to expect company day and night. Since he was completely used to Stephen and me, it was the least we could do to provide him with company. He was also very vulnerable at this time, frequently calling for his brother. Those calls would attract unwanted company like lions and leopards.

You said you were terrified when you released Toki to the main reserve at Ol Pejeta. What threats would Toki, in particular, be most vulnerable to as a human-raised cheetah?

All cheetahs are vulnerable to attack from other predators. The orphans’ mother had been killed by a lion, and Sambu, too, suffered the same fate. Every day, Toki would run the same risk as any wild cheetah of coming into contact with lions, leopards, hyenas, or a coalition of other male cheetahs, all of which would try to kill him. While within the 90,000 acres of Ol Pejeta Wildlife Conservancy, Toki would not encounter any human that might do him harm. But if he found his way out of the reserve he could come into contact with poachers and herdsmen who would not be so harmless.

With so many threats to cheetahs in the wild, do cheetahs ever die of old age or do they usually suffer a violent, unfortunate death?

I have never seen, nor read an account of a wild cheetah dying of old age, though old age may take the edge off their senses, making them more vulnerable to attack or reducing their ability to hunt efficiently. Statistically, a male cheetah is considered getting very old if he reaches seven or eight years, so tough is their life. In captivity they may live a great deal longer; up to double that figure.

Do you think Toki may have ventured into human territory because of his human upbringing and tolerance of people? Would a wild cheetah likely have done the same?

On the contrary, Toki wandered out of the reserve and into hostile country in the north just because he could! The area he visited does have wild cheetah walking through it, as does the reserve itself. I believe he may have felt compelled to keep walking north because he smelt another male cheetah and recalled the near deadly attack he suffered at the jaws of the male coalition in Lewa. I think he was simply looking for a patch of ground where he could be king, or at least where he would be left well alone by other male cheetahs. The fact that there were human beings in the area was entirely incidental to him. He could have no idea that the people he would encounter there might not be friendly. Nor was he seeking human company, just a place to live.

How have Toki and Sambu changed you?

Working so closely with such charismatic, beautiful big cats is a once in a lifetime experience. Sharing time with Toki and Sambu has given me a deeper understanding of these wonderful creatures than I could ever have gleaned with a lifetime of observations in the wild. Simply being with them when they lost their first milk teeth is one example of the privileged contact and observations we had. Being part of their team has been both humbling and enriching beyond words. It has also been very hard at times to make decisions based on pragmatism, when my emotional self has become so closely linked to their fortunes. Very tough decisions had to be made in the face of huge risks. I sincerely hope that Toki and Sambu would agree that we made the right ones, despite their hardships.

Why was it important that this film broadcast on Nature? What do you hope viewers take away from this Nature program?

It is very exciting to think that Toki and Sambu’s story will reach a new audience through Nature. And not just any audience, but one whose care and commitment to ensuring the natural world has an enduring future on this planet is, I am certain, a life priority. I sincerely hope viewers can share something of the wonder and beauty that our experience raising the cheetah orphans has offered us. I also hope that it increases awareness of some of the difficulties faced in contemporary conservation projects. Kenya is a magnificent country with a host of natural riches. But these riches take careful management if they are to be there in perpetuity. I hope that the story of these cheetahs in some way helps to reflect the bigger conservation issues faced by the wild places on this earth.

Anything else that you would like to convey?

If anyone wishes to offer help for Toki and other wildlife in Kenya, then we have set up a trust in his name. The Toki Trust falls under the umbrella of Tusk Trust, a charity devoted to sustainable conservation projects in Africa. Resources raised by the trust will be spent to ensure Toki’s well-being, maintain a sustainable plan for his future and will contribute to the ongoing development of conservation projects in Kenya, most notably in Lewa and Ol Pejeta Wildlife Conservancies.

I will continue to post details of how Toki is getting on, on my own website — www.simonkingwildlife.com — on a regular basis.