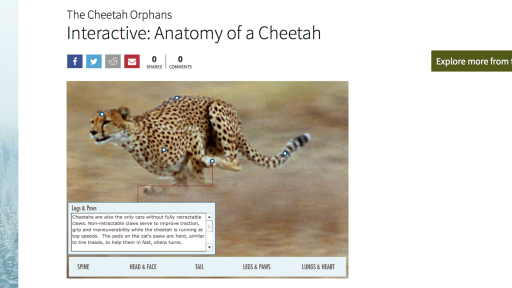

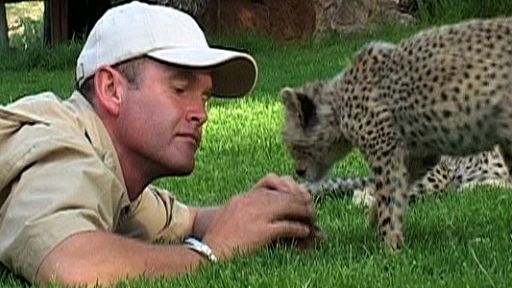

In The Cheetah Orphans, filmmaker Simon King and the team of wildlife professionals at the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, took on the challenge of raising two orphaned cheetah cubs, Toki and Sambu, after the cubs’ mother was killed by a lion. To successfully raise the cheetahs would mean seeing them safely to adulthood and hopefully to a free existence in the wild, where they could eventually parent their own cubs, thus contributing to the cheetah population.

Simon and the cubs would be up against some serious obstacles. Cheetahs face some of the toughest challenges in the natural world, and the survival of the species is in doubt. Loss of habitat due to human encroachment, death at the hands of local farmers, a high infant mortality rate (90 percent!), and a shrinking geographical range are among the factors that limit the cheetah’s survival. Simon and the Lewa team successfully brought the cubs past the critical infant stage, during which they are most susceptible to danger. But Simon’s hardest task in rehabilitating the brothers would be to teach them basic survival skills so they could live on their own, without Simon’s constant supervision. Simon invested thousands of hours to get the cheetahs past the point of danger. In the end, nature claimed Sambu as a casualty, but Simon, along with the other caretakers at Lewa, decided that Toki should continue to live a wild and free existence. Today Toki lives a healthy and, hopefully, happy life in the Ol Pejeta wildlife refuge, where he is safe from most of the threats of the outside world.

In the end, nature claimed Sambu as a casualty. Can the story of Toki and Sambu be considered a rehabilitation success? “Success” in the world of wildlife rescue is a difficult thing to define. According to the National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association, an organization that supports the science and profession of wildlife rehabilitation, the ultimate goal of wildlife rehabilitation is to release injured, orphaned, and diseased wild creatures back into the best possible natural habitat. The outcome of wildlife rescue depends on many individual factors: the particular species being rehabilitated, the starting condition of the animal, and the availability of a safe natural environment for it to return to. Rehabilitation plans and progress must be considered on a case-by-case basis, but the goal is always to end with an animal that is healthy, happy, independent, and — ideally — ready to return to the wild.

Simon spent a great deal of time teaching the cheetah cubs to survive but in the end could not protect them from every threat. Particularly at a sanctuary like Lewa where other wild animals roam, the caretakers can never fully protect the animal without sacrificing some freedom. Toki and Sambu were not a first for Lewa in wildlife rehabilitation. The sanctuary often takes in orphaned wildlife whose parents were the victims of some natural or human act of violence. In 2002, the staff at Lewa received Daisy, an orphaned Oryx. Despite being close to death, Daisy grew to be very independent but still came home every night to sleep in her stable. Daisy even gave birth to a calf during her time at Lewa, living life as a wild Oryx. Sadly, in 2006 Daisy fell victim to an attack by lions. Her calf, six months old, was with her at the time of the incident and survived. Despite her death, Lewa’s staff still thinks of Daisy as a rehabilitation success story; she lived her life in total freedom and managed to have her own calf.

Maria Diekmann is the founder and director of REST, Rare and Endangered Species Trust, an organization dedicated to the preservation of endangered species in Namibia. Though Maria has extensive knowledge of vulture behavior and biology, and in particular the Cape Griffon Vulture, she doesn’t take on the role of surrogate vulture mommy for her orphans. “This is the job I give my other birds,” says Maria. “Typically, the orphan may start out alone in an aviary or with another orphan so it can build up its confidence.” Once it has shown some signs of adjustment, Maria will transfer the orphan to the non-releasable aviary so that he gets used to other birds as well as food competition and the hierarchy within that vulture community. The last stage is for the orphan to bunk with the wild releasable birds so he builds up even more confidence and is better prepared for the wild.

“We have had fantastic results raising baby vultures and getting them successfully back into the wild,” says Maria. Just this year, REST saw a pair of hand-raised orphans return to the center to breed after they had been released to the wild two years ago — the first such case in South Africa of an orphaned, released, and monitored vulture returning to its site of release.

“I held those two birds for two years with other wild rehab vultures from South Africa (in order) to get them used to the climate, area, etc.” The orphans were cared for at a site where REST feeds 350 to 1,000 free, wild vultures each week. According to Maria, that was just what the orphans needed. “They had to act like a vulture, get their food for themselves amongst the others and were only separated by a fence to the free ranging wild birds,” says Maria.

Maria has rehabilitated everything from bats to antelope but says vulture orphans are actually easier than most other species to get back into the wild. The reason, explains Maria, is their highly social nature. Vultures “like to be with each other,” says Maria. “They accept each other easily and use each other for security, etc. at feeds. They allow everyone to eat at any carcass or fly in any thermal even though there is a social order. Vultures like other vultures and this makes any learning curve easier for an orphan.”

Though Maria tries to see as many of her rehabilitated vultures released to the wild as possible, it isn’t always possible. If there is serious injury of other damange that will compromise the bird’s chances of survival in the wild, Maria has to hold the bird permanently at the center. But release to the wild is clearly her main goal. “If he has a chance in the wild,” says Maria, “I must give it to him. People always think it makes me sad to release a bird or any animal that I have spent so much time with, but this is so untrue. Those are my very best days and all that I work for. We can keep the Cape Griffon species alive in captivity — anyone can — but the challenge is can we keep it alive in the wild. That is what they deserve.”

Regardless of the species, rehabilitation is a demanding process, fraught with challenges and triumphs. Rehabilitators will inevitably face difficult choices, such as Simon’s decision to release the cheetah orphans into the wild with so many threats looming. As the main decision-maker and overseer of the fate of the animals, wildlife rehabilitation is a huge responsibility. But it’s also enormously rewarding and an invaluable contribution to the our world.