Click to view the full map. |

In medieval times, the idea that flying, fire-spitting dragons existed was considered entirely plausible. The world was immense and unknown. Many people believed that a sea of darkness encircled the chartered lands. Dragons leapt across the page in the Bible, Beowulf, and Chaucer. And medieval cartographers occasionally illustrated blank spaces with winged serpents and dragons. On the Hereford Mappa Mundi (World Map) in England, several dragon-like creatures appear within its borders.

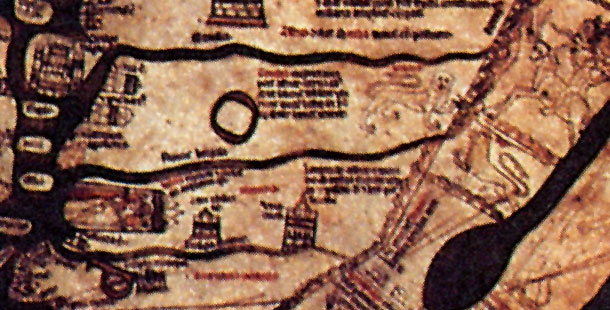

Rom Whitaker, on his quest to find today’s real-life dragons, uses the Hereford Mappa Mundi, the largest medieval map in existence, as a starting point for his journey. He travels to the 1,000-year-old Hereford Cathedral, where the antique vellum the map now hangs. About five feet long and four and a half feet wide, it is encased under thick, security-wired glass — and for good reason: the Hereford Mappa Mundi is one of the most valuable maps in the world. Historians estimate it was drawn around 1290 A.D. with a mineral-based black ink, as well as paints made from vegetable dye, which have now dulled to a warm sepia hue.

Overall, the map is covered in some 500 drawings of the history of humankind and marvels of the natural world: 420 cities and towns; 15 biblical events; 33 plants, animals, birds, and strange creatures; 32 images of the peoples of the world; and 8 pictures from classical mythology.

In the book Mappa Mundi: The Hereford World Map, by P.D.A. Harvey, a glossary is given for the map’s varied creatures and mythical beasts. It writes that dragons were found in India, where they defended the golden mountains. The description continues: “Mythical fire-breathing creature with wings, scales and claws; malevolent in west, benevolent in east.”

Other weird creatures the Mappa Mundi portrays include the bonnacon in Asia, which is drawn moving toward the left but looking back over its shoulder at its own explosion of diarrhea, which, according to the adjacent legend, sprayed a distance of three acres and scalded anything it hit. In Egypt, there is a crocodile and a red salamander with wings, and in Asia, there is a griffin, which resembles a winged Welsh dragon.

Christopher de Hamel, a leading authority on medieval manuscripts, has said the Mappa Mundi “is without parallel the most important and most celebrated medieval map in any form, the most remarkable illustrated English manuscript of any kind, and certainly the greatest extant thirteenth-century pictorial manuscript.”

The creator of the Hereford Mappa Mundi did not work to create an accurate geographical representation, as the creators of maps do today, but rather to glorify the Christian view of the world. As Peter Barber writes in The Map Book, “The Hereford World Map proclaims the insignificance of man and his achievements in face of the divine and the eternal.” He later continues,

At the top one sees the Last Judgment, with the saved to the left and the damned to the right, and a bare-breasted Virgin pleading for mankind. At the bottom right a mounted huntsman looks wistfully back at the earthly world but his pace urges him to move on. The map of the world, like a colossal wheel of fortune, is held down by four thongs containing letters which together spell our ‘MORS’, or death. The map itself has Jerusalem, surmounted by a depiction of the crucifixion, at the center.

Among map historians, the Hereford map is known as a “T and O map,” called such because it looked like a T incised with an O. The T is the Mediterranean, dividing the three continents Asia, Europe, and Africa. The O is the encircling ocean, or ‘Sea of Darkness,’ beyond which lay an uncharted realm that people could only imagine.

Dragons on maps were one of the most significant symbols of what might exist in unknown, far-away lands. The phrase, “Here be dragons,” comes from its use on the Lenox Globe, made in 1500, where it is written in Latin—“HC SVNT DRACONES”—off the east coast of Asia, and denotes what was thought to be a dangerous or unexplored territory.

Whitaker journeys from the Hereford Mappa Mundi to many places that very few medieval Europeans ever went. Rather, they could only see these places on a map (if they were even that privileged), along with a drawing of a dragon, and contemplate them with wonder, and perhaps, fear.

Public domain photograph