To see life on another planet, most would suggest a radio telescope or a NASA explorer vehicle. Yet immediately below the earth’s surface there exists an otherworldly ecosystem populated by creatures that never see the light of day. These animals are the troglobites — crustaceans, amphibians, insects and more — built to survive in the dark, limestone labyrinths that form most of the world’s cave systems.

A pseudoscorpion that doesn’t have a stinging tail and instead injects venom with its claws. A Nelson cave spider with claws on two of its super-long legs that measure just shy of six inches. A whitish, almost transparent cave crayfish that can live over 150 years. These are just some of the troglobites, many of which possess similar evolutionary adaptations: blindness, long limbs and spiky feet to better navigate rocky terrain, and lack of pigmentation as there is no need for camouflage in the dark.

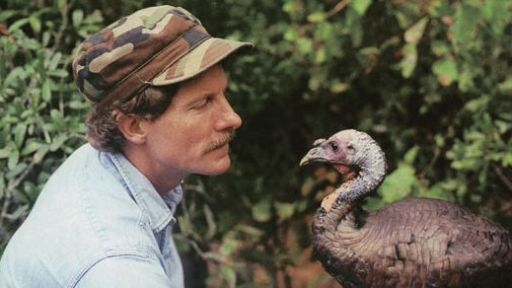

Of all the troglobites, it is perhaps the proteus anguinus, or the olm, that is the star. In Slovenia, a tourism industry exists for those who desire a glimpse of the ghostly salamander that’s beguiled humans for hundreds of years. The first written account of the olm dates back to 1689, in which scholar Janez Vajkard Valvasor disputed the belief that olms were baby dragons. Found in the Dinaric Karst of Europe, it’s easy to see why olms could be fodder for myth. They are blind, yet have barely visible, regressed eyes covered by skin. Their serpentine body can grow over a foot in length, and is covered by whitish, translucent skin that’s artfully highlighted by two frilly pink gills at the back of its head. And, unlike other amphibians that metamorphose into an adult form, the olm retains its larval features, a phenomenon known as neotony. Olms spend their whole lives in water, and so there is no need for them to develop terrestrial characteristics.

In keeping with this fairytale-like appearance, olms are said to be able to live up to 100 years and can go without eating for several. Yes, several years. They, like many troglobites, have exceptionally slow metabolism in large part because of the dearth, or erratic availability, of food. Like other troglobites, the olm compensates for lack of vision by using other, specialized senses. Olms’ ears are capable of receiving sound waves in water and vibrations from the ground, their sense of smell is keener than that of most amphibians, and they possess sensors in their heads called “ampullary organs” that enable them to detect weak electric fields.

Despite such specialized capabilities, troglobites are critically connected to what’s going on above earth’s surface. For a nutritious banquet, some troglobites feast on piles of bat guano found on cave grounds. Tree roots that grow through cracks in a cave’s ceiling and leaves that flow in with water can also provide nutrition. But this water can also bring destruction. Human waste — such as sewer leaks, runoffs, and pesticides — can flow into caves disrupting an ecosystem so sensitive it is said that even human dandruff can upset its balance.

Excavations and the building of roads can also threaten cave life directly. It’s important to note that most of the world’s caves have yet to be fully explored or discovered. The limestone labyrinths beneath us are indeed the earth’s last frontier. It’s a fascinating notion –- some of us may be living above an ecosystem populated by strange species, some millions of years old, and not even know it. In 2007, environmental protection officials in Australia halted a multi-billion dollar iron ore mining proposal when 11 species of troglobite were discovered in the area to be mined. Unfortunately, the ruling was overruled several months later. The battle between moneyed interests and our wildlife continues, unfortunately with greater frequency and scope.

Troglobites are at great risk. This includes the beloved olm which is presently listed by the IUCN as threatened, a circumstance that should be taken very seriously, not only because we should be stewards of our planet (above its surface and below) or because the olm is a fascinating, wonderful species, but also because it is the olm’s very sensitivity to such things as pollution that portends what affects humans as well.

Photo © WNET.ORG/Icon Films