Before Dian Fossey’s landmark research with the mountain gorillas of Rwanda, people imagined that gorillas were dangerous beasts that lurked in the forest and would attack humans that ventured into their realm. But decades of research, tracking gorillas day by day through the misty forests of the Virunga Mountains, has shown that they are basically gentle creatures with individual personalities and rich social lives. In fact, if you could spend time with the gorillas in their verdant mountainside habitat, you might be surprised to find that their family dynamics and political maneuvers are quite complex — in some ways, almost “human.”

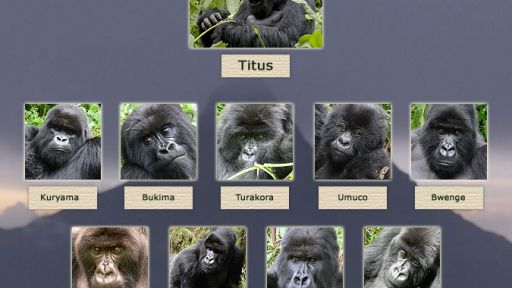

A gorilla family is usually comprised of three to thirty individuals, though in late 2006, Karisoke researchers in the Virungas were monitoring one group that had reached sixty-five individuals. Like Titus’s family, a typical group is led by one silverback — a mature male, so-named for the graying hair on his back — who serves as the family’s protector and main decision-maker. He is usually joined by one subordinate silverback that will help defend the group, several adult females, and a combination of younger males (“blackbacks”), juveniles and infants. Gorillas communicate in a variety of ways, including facial expressions, sounds, postures and gestures. They have been known to make at least 22 distinct sounds to communicate different feelings, from playful chuckling to frightened screams — even belches of contentment. Gorillas are affectionate creatures. In February of 2008, Karisoke researchers discovered that an adult female had been injured in an encounter with a silverback. After the injury, a younger female stayed close by the gorilla’s side, behavior that Veronica Vecellio, featured in The Gorilla King, says is evidence of the young gorilla’s kind personality. When things are calmer, gorillas often greet each other by touching their noses together, and will sometimes even give a reassuring embrace.

The females align themselves with their leader, openly soliciting mating. It is the silverback’s job to keep the group safe from outsiders, but it pays to be in his good graces. In moments of danger, he will beat his chest and intimidate or fight with an attacker while the rest of the family flees to safety. If a conflict erupts within the group, the silverback mediates between fighting family members. The silverback also knows where to find the best food sources throughout the seasons, and he leads the group in their daily travels, up to about half a mile each day. Each evening, mountain gorillas settle to dine on nettles, bamboo, and other plants. An occasional grub or colony of ants spices up the menu. Sometimes, the silverback will start to sing if he finds a particularly lush patch of greenery. As the family gathers round, others may join in the chorus. As night draws near, the adults will make a nest of flattened foliage for sleeping. Then, each morning, the group sets off again for a new home and new food source.

When the afternoon comes, however, it’s family time. The adults build day nests and leisurely graze and rest together while the youngsters play. Moments like these reveal the tender bonds that form in gorilla families, especially between mothers and children. A newborn gorilla baby will form a very close relationship to its mother — rarely straying more than a few steps from her side for the next three to four years. Baby gorillas learn by imitating, much like human children, though gorilla babies develop more quickly. They can walk at about six months old, and after about a year and a half, a young gorilla can follow its mother on foot for short distances. Before long, the youngster will be exploring, climbing trees, play-fighting, and even walking hand-in-hand through the forest with the group’s other infants.

Internal relations are not always so smooth, however. As Titus’s reign in The Gorilla King shows, an aging silverback will sometimes face a challenge from an aggressive, younger silverback in his own group. The balance of power may shift slowly over time, until the up-and-coming male has convinced the clan that he is the one with the strength to lead. A new silverback leader is likely to kill the infants in the group, so the nursing females will stop lactating and their reproductive cycles will restart. Murdering the young of other males thus makes it possible for the new silverback to sire children of his own.

His violence and posturing may earn him respect, but don’t assume that the silverback is always in control. Females have been known to go behind the leader’s back to mate with other males, confusing them into thinking that the babies might be their own — and earning their protection in case of danger. But overall power, in part, comes from the support of the females in a group. If a leader cannot keep their respect, they will leave. The females also wield some power in the event that a silverback leader dies. If another silverback attempts a takeover but the females don’t approve, they may abandon him and seek another male to take care of them.

High on the Virunga volcanoes is an entire social world that humans still strive to fully understand. A closer look at the lives of the mountain gorillas shows that they are not monsters at all but complex creatures with families, affections, and politics of their own.