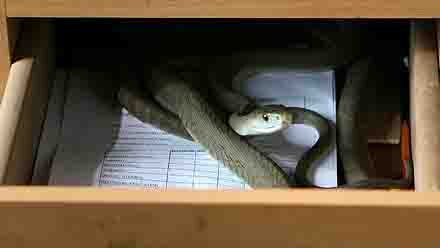

Black-footed ferret in a captive breeding program at the Black-Footed Ferret Conservation Center

There are 16,928 species currently listed as threatened, and the present world-wide extinction rate is 1,000 to 10,000 times higher than the natural rate. Faced with such overwhelmingly drastic figures, what can we do, and what should we do? For some of the loneliest animals on the planet, captive breeding programs and human intervention may be the only hope. As habitats continue to shrink, scientists and conservation biologists face an increasingly daunting task. Still, they must try to do what they can. For some species it is too late. Hopefully, for others, it may be a new beginning.

Captive breeding programs with the goal of reintroduction have existed since the 1960s. One of the first successful programs was the reintroduction of the Arabian oryx. The Arabian oryx is a striking and elegant white ungulate that roamed the Arabian Peninsula in large numbers until they were hunted to extinction in the wild in 1972. The Phoenix Zoo (in Arizona?) started a captive breeding program in 1962, and from 9 individuals, over 200 young were successfully bred. These oryx were distributed to zoos around the world, and many more herds were started in captivity. In 1982 the first Arabian oryx were reintroduced to Oman, where their numbers increased over the next two decades. Currently there are reintroduced populations in Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Israel, with a total population of approximately 1,100 individuals. The populations in Saudi Arabia and Israel are increasing; however, the population in Oman at the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary has shrunk from a high of 450 individuals in 1996 to only about 50 oryx in 2008. This is largely due to illegal (capturing – what is capturing if not poaching?) and poaching, and the degradation of the sanctuary after the Omani government decided to open up 90% of the park to petroleum prospects. Sadly, the 50 remaining oryx in Oman are all males. Unless someone steps in to help, this population will disappear.

The plight of the Arabian oryx in Oman is not the only story of its kind. Over and over again the same conclusion is reached: captive breeding and reintroduction programs cannot succeed without long-term wild habitat preservation and protection.

In 2007, 100 Arabian oryx were released into a fenced off area of wilderness in the United Arab Emirates, the first step of a new reintroduction program that plans to release 500 oryx by 2012. So depsite the loss, yet again, of the Arabian oryx in Oman, perhaps there is still hope for the species. As with all captive breeding programs, there is always a glimmer of hope, and in the face of massive extinctions of the world’s organisms, any steps necessary to grant a few species a second chance is well worth it.

More recent captive breeding success stories include the California condor, black-footed ferret, golden lion tamarin, and red wolf. In order to survive once released, animals must be taught basic survival skills in captivity. Some skills come innately to some species, but others must be learned socially. They must learn how to find food, avoid predation, attract a mate, and build or find adequate shelter.

All this training, in addition to other costs, can add up to quite a large tab for captive breeding programs. The most expensive captive program ever was the California condor reintroduction program, which has cost over 35 million dollars since 1987, when the last 22 wild California condors were captured and the program began. In the early years of the program, many reintroduced California condors died after release due to lead poisoning, and collisions with power lines. Since 1994, however, captive-bred condors have been trained to avoid power lines, and the number of deaths associated with them has greatly decreased.

It takes time to figure out what is best for a species and to build a successful reintroduction program based on that knowledge. The goal of captive breeding programs is not to just increase population numbers, but to give those new individuals a better chance of survival. How to best limit the dangers to animals after their release, and how to monitor their success are both important facets of captive breeding programs. Lead poisoning, for example, could not have been anticipated. California condors have extremely potent digestive acids that dissolve lead bullet scraps to the point where they can be absorbed through ingestion. To circumvent that problem, in 2008, the Ridley-Tree Condor Preservation Act, a federal bill that prohibits hunters from using lead bullets in the California condor’s range, went into effect. It proved once more that federal protection and environmental legislature are critically important aspects of conservation efforts. Behind the work and care of every human involved in captive breeding, there must be funding, and there must be public support. Without them, these last ditch efforts to save entire species or subspecies would not be possible.

Works Consulted:

Curio, E. (1996) Conservation needs ethology. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 11(6): 260-263

Griffith, B. et al. (1989) Translocation as a species conservation tool: status and strategy. Science, 245: 477-480

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2008) Oryx leucoryx. Retrieved April 1, 2009 from

http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/15569.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2008) 2008 Red List summary stats. Retrieved April 1, 2009 from

http://www.iucn.org/about/work/programmes/species/red_list/2008_red_list_summary_statistics/.

Sample, Ian. (2 July 2008). Wildlife extinction rates ‘seriously underestimated.’ The Guardian.

Retrieved April 1, 2009 from

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/jul/02/climatechange.endangeredspecies?fb_page_id=15041226930&.

Toone, W.D., Wallace, M.P. (1994) The extinction in the wild and reintroduction of the

California condor (Gymnokyps californianus), in Creative Conservation: Interactive

Management of Wild and Captive Animals (Olney, P.J.S., Mace, G.M. and Feistner, A.T.C., eds). Chapman & Hall: 411-419.

Captive Breeding and Species Reintroductions

http://www-personal.umich.edu/~dallan/nre220/outline23.htm.