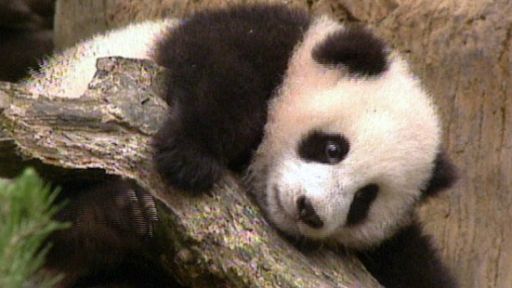

A baby’s arrival is always a big event. But rarely is a newborn greeted by international headlines and a world eager to follow every twitch of its four-ounce, fist-sized body.

Hua Mei’s birth made international headlines. On August 21, 1999, however, animal lovers the world over rejoiced as Hua Mei became one of just a handful of baby giant pandas ever to be born in captivity. This week, NATURE’s The Panda Baby tells the inspiring story of this pint-sized arrival — the product of years of focused and often frustrating work by scientists and conservationists in China and at the World-Famous San Diego Zoo in California.

Native to the misty bamboo forests of central China, giant pandas are among the best known — and most endangered — animals in the world. Scientists have named them Ailuropoda melanoleuca, meaning “black and white cat-footed animal.” In China, they are known as Daxiongmao, which means “large bear cat.”

But conservationists estimate that only about 1,000 of the big black and white bamboo-eating bears remain in the wild in China, where they are threatened by habitat loss and hunting. Another 140 live in breeding facilities and zoos, with about 20 of those captive bears living outside their homeland. In the United States, just three zoos — in Atlanta, San Diego, and Washington, D.C. — shelter pandas. The animals are precious, with the zoos paying up to $1 million a year to the Chinese government for the privilege of “borrowing” the animals for display and study.

For years, biologists have hoped that they might learn to breed these captive bears, in hopes of ensuring the animal’s survival. But it has been a long and frustrating process. Faced with little understanding of panda behavior and biology, some zoos have been unable to create just the right conditions to spark a panda romance. Others have succeeded in getting their female pandas pregnant, only to have the cubs die within days of birth. With each heartbreaking failure, the puzzle of panda reproduction seemed to grow even more complicated.

In 1997, however, the San Diego Zoo got a chance to take another crack at the problem. Home to the Center for the Reproduction of Endangered Species (CRES), the zoo has become world-renowned for figuring out how to get rare and threatened animals to reproduce. Hoping that CRES could help them solve the panda challenge, Chinese scientists loaned the zoo a pair of the animals for 12 years.

They made quite a couple. Bai Yun was a frisky five-year-old female — one of the first captive-born pandas produced by the Chinese. At 20, male Shi Shi was also an interesting story. He had been severely injured in the wild, and was nursed back to health. But his injuries were too severe to allow him back into the bamboo forests.

From the very start, the zoo staff took every possible step to ensure that they would eventually be able to roll out a birthday cake. The pandas were coddled and carefully cared for. But after two breeding seasons, they had little to show for their hard work. The panda couple wasn’t even getting along. So their human caretakers interceded, artificially inseminating Bai Yun with sperm taken from Shi Shi.

Finally, in their third breeding season: success. Resembling a pink rat more than a giant panda, Hua Mei was born. Over the next few months, her every move was monitored by zoo staff and a legion of “panda-maniacs,” who follow the little girl’s daily drama on the World Wide Web.

Hua Mei and Bai Yun have parted ways. Recently, Hua Mei reached the next phase of her closely watched life. On February 23, 2001, zoo officials announced that Hua Mei was permanently weaned from her mother. The process of separating mother and daughter was delicate. Over three weeks, the two spent more and more time apart in their specially built enclosures. Six hours apart stretched into 12. Then, finally, the mother and daughter parted ways forever, just as they would in the wild.

“Giant pandas are solitary animals by nature, and by this stage of development in the wild, panda cubs and their mothers would be parting ways and seeking their own territories,” says Don Lindburg, giant panda team leader at the San Diego Zoo. “Hua Mei is fully capable of eating on her own.”

A panda diary maintained on the zoo’s web site also notes that pandas “do not live in families like humans. Neither mother nor infant showed any realization that a change had taken place … [and there is] no indication that either the mother or infant [is] upset by being apart.” Eventually, panda fans hope Bai Yun may have another cub — and Hua Mei may herself become a mother.

Meanwhile, hopes are springing anew at another American zoo. In December 2000, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C. received a new pair of pandas to replace a beloved pair that had died years earlier. The pandas — 2-year-old female Mei Xiang and 3-year-old male Tian Tian — come from the China Research and Conservation Center for the Giant Panda in Wolong, Sichuan Province (the center featured on the The Panda Baby).

“We are thrilled to bring a pair of giant pandas back to the National Zoo,” says director Lucy Spelman. “Tian Tian and Mei Xiang are young and full of energy, and they are incredible creatures. But it is important to remember that both were born in a breeding facility in China and that their wild counterparts remain highly endangered.”

Even with the growing success of breeding programs, “the panda is not safe,” agrees George Schaller, a noted panda expert with the Wildlife Conservation Society. “It will always be threatened by something,” he says, “attracting adversity as readily as adoration. We know what the panda needs: a forest with bamboo, a den for its young, and freedom from persecution.”