If it weren’t for the lady and the panda, the world might never have fallen in love with the lovable black and white bears. In the early 1930s, pandas were as much myth as reality outside of China. Few westerners had ever seen one of the animals alive; they were known primarily from a few trophies taken by big game hunters, including Theodore Roosevelt in 1929.

Ruth Harkness went on an expedition to China. Roosevelt’s prize, however, helped spark several expeditions to capture a live baby panda and return it to the United States. One of the adventurers was the independently wealthy William Harkness, who had made a name for himself capturing Komodo dragons — giant lizards — in the Dutch East Indies. In 1936, Harkness set off for China, promising to bring a panda baby back alive. Before his adventure could begin, however, he fell ill in Shanghai and died. Back in the U.S., Ruth Harkness, his recent bride, learned that she was a widow. Within days, according to WASHINGTON POST MAGAZINE reporter Vicki Croke, Ruth “declared that she had ‘inherited an expedition.'”

“More in the spirit of a Hollywood romp than of a scientific endeavor, Harkness set sail from New York City on April 17, 1936,” Croke noted in a March 4, 2001 story, “hosting a cocktail party in her stateroom, with dozens of swells juggling highball glasses and cigarettes and teasing her about her far-fetched mission.”

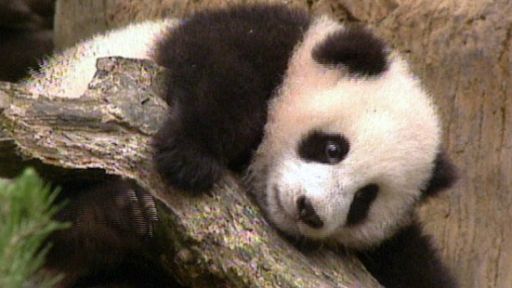

The socialite adventurer proved up to the task. After an arduous trip into the mountains, and some controversy over the methods used to capture the baby panda (another expedition said it was “their” animal), Harkness returned to the U.S. in December 1936 carrying the first live panda to set paw on American soil. The result, as headline writers put it, was “panda-monium.” Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo, which eventually bought Su Lin, as the panda was named, had its biggest visitation day ever when it went on display.

Soon, zoos around the world were scrambling to obtain their own animals. Between 1936 and 1946, according to the World Wildlife Fund, 14 pandas were taken from China by foreigners, leading to a ban on the captures. Soon, however, China began to use pandas as goodwill ambassadors, giving pairs to Russia, the United States, Mexico, Germany, and others. Two dozen pandas were given away between 1957 and 1983.

As for Harkness, she would return to China several times and even come back to the U.S. with another panda. She would eventually write a well-received book, THE LADY AND THE PANDA, about her experiences.