Got a ‘gator in the garden, and don’t want him there? Then call Todd Hardwick.

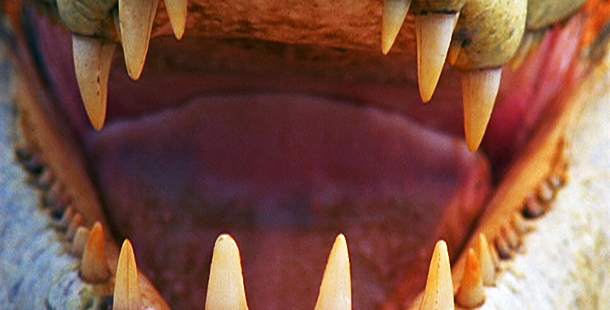

Hardwick, 40, is one of Florida’s three dozen licensed alligator trappers. When worried citizens call state officials to report a nuisance alligator, the state calls on experienced trappers like Hardwick to size up the situation and recommend whether the big lizard should stay, go, or, in some cases, be killed. In 2001, Floridians phoned in 17,000 alligator reports, resulting in the relocation or deaths of more than 5,000 alligators. Under state rules, problem alligators smaller than 4 feet long are typically moved into one of the state’s preserves, but bigger animals may have to be killed.

As Part 1 of NATURE’S The Reptiles series shows, Hardwick’s job requires equal measures wildlife biology, teaching skill, and brute force. Sometimes, he simply needs to educate a frightened homeowner about alligator habits.

Hardwick runs a successful business called Pesky Critters that responds to hundreds of calls a year on everything from problem possums to marauding monkeys. Some of his captures have ended up on his spacious 7-acre farm, which often holds 100 animals or more and sponsors educational programs. Hardwick recently chatted with NATURE in between calls for help.

How did you get involved in this business?

I’m a native Floridian and growing up, I spent my time running around vacant land catching and watching animals. I didn’t want to go to the mall and play Pac-man. I even learned how to catch small alligators. By the time I was in high school, I was catching problem animals in exchange for movie and pizza tickets.

I got a lot of ridicule. People would ask me: “What kind of a job is possum catcher?” I thought it could a good one. Increasing human population was causing loss of habitat, and when there are more people and less habitat there are going to be conflicts. Most people aren’t very good in hand-to-hand combat with an opposum. So I’ve been doing it for 22 years now, and have captured tens of thousands of animals. It’s not a job for me, it’s a lifestyle.

Where do alligators fit in?

Well, [catching nuisance] raccoons and opossums is the bulk of my business. But from April to July, I pretty much run around chasing alligators. During those four months, it is just crazy because it’s alligator breeding season. The weather warms and they become very active, and start looking for romance in all the wrong places. I’ll have 50 to 75 complaints at a time in my territory, which stretches 220 miles from Fort Lauderdale to Key West. And it just keeps getting busier.

That’s a big change from when alligators were considered to be threatened with extinction, isn’t it?

When I was young, the alligator was an endangered species. Today, we call them a nuisance. There are over one million alligators in Florida — it’s a tremendous success story. But while we were helping them come back, we weren’t stopping development. So there’s a big misconception about who has moved into whose neighborhood. I’ll go visit someone who’s screaming about an alligator, and I’ll remember the area as being a wetland five years before. So I remind them that that they are the ones who bulldozed the wetland. I want them to understand that they are the invader here, not the alligators. I’m almost an ambassador for the alligator.

When I’m out there, I do all sorts of education. One of the biggest problems is that people living in Florida are from everywhere except from here, so they don’t know how to behave in alligator country. [I remind them that] the number one problem is people feeding alligators. It conditions them and takes their fear away. But you can’t tell a mom that a 9-foot gator is not a threat to her toddler — it is. They are conditioned to hunt small animals that are low to the ground. Gators eat dogs so commonly in Florida that the state refuses to keep records.

How do you decide if an alligator needs to be killed?

The good news is that there is a clear process. If the alligator meets certain criteria [including size], whether it is a threat to people, property, or pets, then it may have to be killed. But even if I have to kill one of my favorite alligators, I realize we may be preventing a possible human fatality. It also benefits the rest of the alligator population. By preventing any attack we can save thousands of alligators. That’s because when an alligator grabs someone there is tremendous publicity. People panic and want every alligator in the area removed.

Have you had any close calls?

I’ve been hospitalized several times for bites from raccoons, possums, and skunks. But fortunately I’m very good at what I do and have only been bitten once by an alligator, and it was a very mild bite. But you can never drop your guard. Even a 6-foot alligator can easily drown you. My health insurance company was very hesitant to insure me years ago, but now if I go in and can show I still have ten fingers, I get a renewal!

How big was the biggest alligator you’ve caught?

It was 12 foot, 7 inches and weighed 425 pounds. I’ve also caught a 22-foot, 250-pound reticulated python. It had been turned loose in a state park, and grew over 10 or 12 years. Then it grabbed a raccoon and went under someone’s house. We pulled it out and zipped it into a sleeping bag. Then I got on a plane with it to California, to be on the Johnny Carson show.

South Florida is unique — it’s almost like an open-air zoo. All of these pets that people release don’t die, they thrive. I’ve handled animals from all over the world without leaving home. I’ve captured escaped mountain lions, stampeding buffalo, and several hundred monkeys (it’s one of my specialties). Anything you can think of has, or will be, loose down here. And I’ll be the guy chasing it.

Where are you headed now?

I’ve already got 2 raccoons and a possum in the truck. I’m heading to a golf course where a 10-foot alligator is supposed to be intimidating golfers. I told them they should just put up a sign up that says “alligator hazard.”