In the clear waters off the coast of North Carolina, the wreck of the submarine “Tarpon” lies broken and battered on the sea floor. The haunting wreck alone is enough to attract divers.

But in recent years, curious throngs have swum down to the site to see something else: sharks. Each spring and autumn, hundreds of Ragged-tooth sharks gather at the wreck to mate, stirring up the sand with the kind of rough-and-tumble courtship rituals seen on The Secret World of Sharks and Rays. Divers even find shark teeth littering the bottom, broken off during mating as the males clasp their jaws around the females. The “Tarpon,” however, is just one destination in the increasingly popular sport of shark diving. Last year alone, researchers estimate more than 200,000 people swam into the deep to feed and commune with schools of small sharks — or climbed into a protective steel cage to get up close and personal with potentially dangerous animals like the Great White shark. Many additional tourists took the safer option of swimming with rays.

“How many of your friends have ever petted a six-foot nurse shark?” asks an advertisement from a California-based shark diving company, one of hundreds that have sprung up in recent years from Australia to the Bahamas. For a fee, this firm and others will put you at the center of swirling schools of sharks ready to eat fish out of your hands. Most companies, however, have trained guides clad in bite-proof suits do the feeding while clients watch and get some close-up pictures. Some guides even use heavy chain-mail protective suits, much like Knights of the Round Table used to wear.

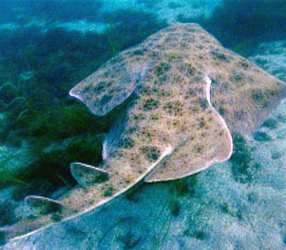

When it comes to rays, however, such protective measures aren’t necessary. In the Bahamas and elsewhere, divers can find themselves amidst a flock of hungry, flapping rays, eager to snatch squid treats from onlookers. Some guides even claim the rays look forward to human visitors and enjoy being petted and stroked.

Sometimes, however, shark diving requires people to huddle behind bars. When the quarry is Great Whites, Tigers, and other potentially deadly sharks, divers often descend to the sharks’ territory in protective cages. At Australia’s legendary “Scuba Zoo” on Flinders Reef in the Coral Sea, for instance, businessman Mike Ball has built a huge 60-foot-long metal cage on the sea floor. While divers feed the area’s many sharks, onlookers can watch the action from inside the cage or, if they dare, from outside the bars. The cage can be surrounded by up to 30 sharks at a time. While some conservationists are concerned that such feeding operations may make wild sharks too dependent on people, many hope the growth of shark diving will make it more valuable to leave sharks in the seas than to kill them.

They note, for instance, that shark diving can help employ small-scale fishermen who now spend their days catching sharks. Already, divers have shown they are willing to spend big bucks on sharks. For instance, it costs more than $3,000 each for the opportunity to swim with giant Whale sharks, and hundreds of dollars to spend a few hours with more common sharks. In the Bahamas alone, more than 20,000 divers participate in shark dives each year. Shark conservationists are hoping that, like bird watchers before them, shark watchers will soon become the vanguard of a movement to protect the world’s imperiled sharks.