Sharks come in a dizzying array of shapes and sizes. Here are profiles of just four of the more than 350 known species.

The Wobbegong

The Wobbegong, or Carpet shark, is a pudgy, toad-like bottom dweller common along the coast of Australia and the warm waters around other Pacific islands. As THE SECRET WORLD OF SHARKS AND RAYS shows, the Wobbegong has short, wiggly tendrils around its mouth that resemble seaweed, fooling small fish into thinking the shark is a place to hide. Off Australia, the Wobbegong “is usually the first shark a diver encounters,” says Stephen Bilson, a Down Under diver who runs a Web page dedicated to sharks. “The first time I ever saw a Wobbegong, I was down on the wreck of the ‘Scottish Prince’ on the Gold Coast of Queensland. The instructor called us to him and was pointing to a part of the wreck. When I got there, I got the shock of my life! Here within about 18 inches of my face were what I considered to be huge animals. There were a whole bunch of them lying on top of each other, the largest about five feet. It was a magical experience for me.”

“If you haven’t seen a Wobbegong,” Bilson says, “they are extremely well camouflaged. I’ve seen many divers kick them, stand on them, or run into them. That is really the biggest danger. It must always be remembered that these are big fish with teeth, not really scared of divers. I’m not saying they are a dangerous species of shark — I’m just pointing out that if you provoke one, it might bite you. If they do bite you, they have a tendency to hold on.”

Basking Shark

Though Whale sharks are the world’s largest shark, Basking sharks come in a close second, growing to over 30 feet long. Like Whale sharks, Basking sharks are gentle creatures that feed on plankton. They live around the world, cruising along the surface at five or six miles an hour, filtering plankton from the water with enormous gills, specially adapted to work like strainers. A single shark can filter a volume of water equivalent to that found in a 150-foot long swimming pool every day. Remarkably, the huge sharks, which can weigh more than 3 tons, sometimes make spectacular leaps out of the water, crashing back into the waves with an enormous splash. Researchers are not sure why the great fish make the leaps, but it may be to remove parasites or to communicate with other sharks. Unfortunately, Basking sharks are under heavy pressure from fishing fleets. Their livers, which can account for up to one third of their body weight, produce a valuable oil used to lubricate engines and manufacture cosmetics. And their dorsal fins, which can be six feet high, are valued for soup. As a result of overfishing, Basking sharks are now believed to be extinct in some areas they once inhabited.

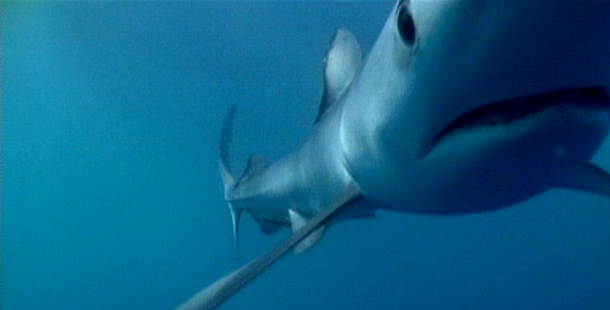

Great White Shark

One of the gentle Basking shark’s closest relatives has a very different reputation: the 10- to 20-foot Great White shark has been celebrated in books and movies as a ruthless man-eater. But scientists say the Great White, which lives in the warm seas of the world, has gotten a bad rap. Although Great Whites do attack people, the attacks are rarely fatal and the threat is exaggerated.

In fact, other kinds of sharks are responsible for more fatal attacks and, overall, more people are killed in the U.S. each year by dogs than have been killed by Great White sharks in the last 100 years. Still, Great Whites are prodigious hunters, able to tackle giant tuna and even sea lions and dolphins. After eating a large meal, however, a Great White can survive up to a month without another morsel. Like most sharks, Great Whites sometimes lose teeth in the process of hunting, but they don’t mind this: the teeth regrow within days. Over a lifetime, in fact, sharks may go through thousands of teeth.

Researchers believe Great Whites spend most of their 40-year lifespans hunting alone, but because the sharks are relatively rare, very little is known about their habits. Some researchers believe that the biggest Great Whites are rarely seen, because they retreat to the depths of the ocean. Other scientists believe that the big sharks, like some other species, change sex when they reach a certain size: males become females. The switch may ensure survival by allowing the largest, most experienced sharks to give birth to young.

Tiger Shark

Though Great Whites have gotten the man-eating reputation, the Tiger shark is the fish people should fear. The menacingly-striped torpedo has been responsible for more fatal attacks on humans than any other shark. But as THE SECRET WORLD OF SHARKS AND RAYS shows, Tiger sharks don’t discriminate when it comes to snacking: they will eat almost anything from sea turtles to tin cans. They also eat other sharks. In one case, in fact, snagging a Tiger allowed an angler to catch four sharks at one time: the fisherman caught a Tiger that had a Bull shark in its stomach, which had a Blacktip shark in its stomach, which in turn had a small Dogfish in its stomach! Like Great Whites, Tigers apparently live nomadic lives, roaming the warmer coastal seas. They are known to travel more than 60 miles a day. The Tiger apparently lives up to 40 years and can grow up to 16 feet. Its name comes from the dark stripes that decorate its back, though some Tigers lose their colors as they age. Female sharks produce up to 80 young at a time. Luckily, the Tiger isn’t generally considered a valuable food fish, so its numbers have remained strong.