In 1997, “Under Antarctic Ice” filmmaker Norbert Wu journeyed to Antarctica for the first time on a special grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. government’s leading funder of scientific research on the frozen continent. But the United States isn’t alone in conducting research in Antarctica. Currently, 17 other nations — from Russia and China to Brazil and Uruguay — also operate Antarctic research centers. And each year, thousands of scientists (and even a few filmmakers) get to visit these remarkable laboratories, and conduct studies focused on everything from the world’s climate to the land mass locked beneath the ice.

Antarctica has long been a magnet for scientists due to its size, location, weather, and isolation from the rest of world. It is among the most pristine places on earth, making it a perfect spot to study how pollutants travel through the atmosphere. Sadly, polar researchers have found that even deadly toxins, such as mercury, can travel vast distances and end up in Antarctic snow, plants, and animals. And in the 1980s, they realized that chlorine compounds routinely used in aerosol sprays, air conditioners and other products were carried to Antarctic skies, where they ate a hole in the protective ozone layer, letting in dangerous ultraviolet light. Such studies led directly to an international agreement to reduce the use of ozone-eating compounds.

Today, Antarctica is a key outpost for global warming studies. Cores taken from its thick ice sheet hold tiny air bubbles that have allowed scientists to track the historical buildup of the global warming gas carbon dioxide, formed by burning fossil fuels. In essence, the cores are time capsules that reach back thousands of years, to a time when there was less carbon dioxide in our skies. And the continent’s massive sea ice sheets may act as an early warning system for warming’s arrival: Some scientists say the recent collapse of several major sheets signals the beginning of a potentially dangerous warming period. Water locked in polar ice, for instance, could be released, helping raise sea levels and flood coastal cities.

Antarctica is also among the darkest places on earth, with its inky winters lasting nearly half the year, making it ideal for astronomers. They have built state-of-the-art telescopes that sweep the skies for celestial objects created at the birth of our universe. Antarctica’s location at the bottom of the globe also means it sits at a perfect place to study Earth’s gravitational and magnetic fields, making it a haven for astrophysicists. And in the future, the polar ice may help provide a kind of shield for a deep-buried instrument designed to spot neutrinos, mysterious high-energy particles produced by the exploding stars and other objects. Scientists want to bury the instrument, dubbed “Ice Cube,” so that the ice helps sift out unwanted atomic particles. The ice also holds amazing meteorites, including some that started life as rocks on the surface of Mars.

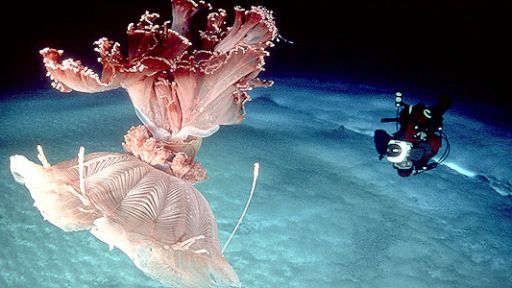

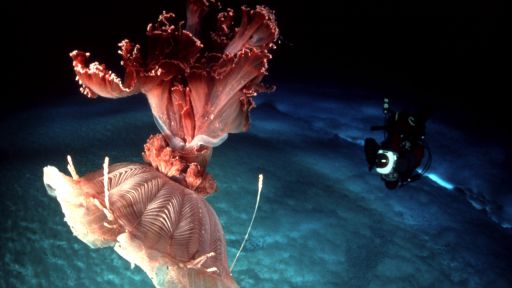

Marine biologists love Antarctica because its seas are filled with remarkable but poorly understood creatures, from fish and crustaceans that make their own anti-freeze to whales and seals that travel thousands of miles in search of food. And on land, researchers are amazed by the ability of some plants and animals to survive the harsh conditions. There is even a huge underground lake locked thousands of feet beneath the ice, called Lake Vostock, that scientists believe may hold specially adapted life forms found nowhere else on earth. They are trying to design a special probe that could drill and melt its way into the lake and collect water samples without contaminating it with bacteria or pollutants from the outside world.

Scientists also value Antarctica because it is a land without borders. Under an international treaty, Antarctica is open to all, and scientific findings are shared. Many projects are multinational, and a visit to any base is often an experience in multiculturalism, with scientists from around the world sharing common quarters.

Of course, getting there isn’t easy. While many of the bases are perched on the continent’s edge, and can be reached by icebreaking ships in the right season, others are inland, sometimes right at the South Pole itself. In places, travel can require special aircraft equipped with skis, helicopters, and rugged snow buggies that crawl across the ice on tank treads. While traffic may be sparse, the drivers still have to be careful, because you never know when a crevasse may appear before your vehicle and threaten to swallow it whole. And even minor breakdowns can be life-threatening if you aren’t prepared for the weather.

Still, most scientists relish the opportunity to work in Antarctica. A hardy few even stay throughout the winter, spending months in near-total darkness, cut off from supply flights. The scientific rewards, they say, are well worth the sacrifice.